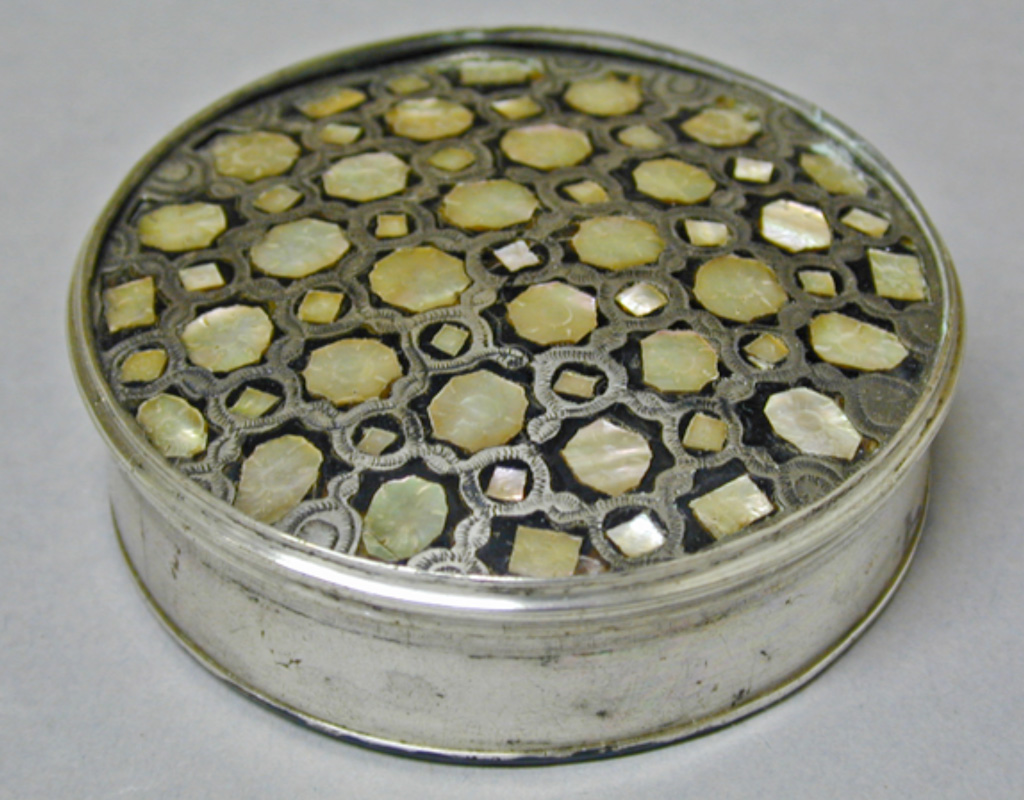

Patch box

Italy or Britain, c. 1750–1850

Bequeathed by Estella Louisa Michaela Canziani in 1965; 1965.9.103This circular tin, around 6cm in diameter, has a metal body but the bottom and the lid are made from tortoiseshell. The lid is inlaid with rows of small flowers in mother-of-pearl so thin as to be translucent when held to the light. It is believed to have contained beauty patches, little pieces of fabric that were stuck to the face to hide blemishes and scars caused by disease or act as a beauty accessory.

Bequeathed by Estella Louisa Michaela Canziani in 1965; 1965.9.103This circular tin, around 6cm in diameter, has a metal body but the bottom and the lid are made from tortoiseshell. The lid is inlaid with rows of small flowers in mother-of-pearl so thin as to be translucent when held to the light. It is believed to have contained beauty patches, little pieces of fabric that were stuck to the face to hide blemishes and scars caused by disease or act as a beauty accessory.

The beauty patch originated in Ancient Rome where blemishes such as birthmarks or moles were regarded with superstition. In 16th-century Europe they were a good way of concealing the scars caused by disease such as smallpox or the 'great pox' (syphilis). Influenced by artistic and cultural shifts however, the patch went from being a mark or shame to a mark of pride. During the Renaissance, the female ideal had been that of the 'virago', that is, an assertive, plain and masculine woman. With the dawn of the Baroque period, cosmetics came back into vogue.

Conspicuous black patches were made out of expensive materials like silk or velvet and cut into shapes such as hearts, circles, diamonds, stars and crescent moons. Women pasted them on the face, neck, and breast, according to a newly emerging language of symbolism: a patch above the lip meant coquetry, on a forehead, grandeur, and at the corner of an eye, passion. Every lady carried a patch box such as this, made of tortoiseshell, silver or ivory. In 1649, the year of Charles I's execution, and amid the ascent of Puritan principles, a bill was set before Parliament calling for the banning of 'The Vice of Painting and Wearing Black Patches and Immodest Dresses of Women'. The bill was never passed, however, due to its impracticability.

With the playful and florid Rococo style of the 18th century, the prevailing feminine ideal became one of fragility, frivolity and coquettishness. In an artistic metaphor, the beauty patch served to interrupt the regularity of the face, rendering it more asymmetrical – a key element of Rococo art. It also suggested a beauty defect, which was perceived to endow the woman with a perverse charm. Its popularity led to a fashion for patches dyed in rainbow colours. In Queen Anne's day (1702–14) politically conscious ladies even wore their patches in such a way as to signify their support for either the Tory or the Whig party.

Fashions come and go and although the patch was never fully revived, the beauty spot – a natural or artificial 'mole' positioned off-centre above the lip – was revived by the 1950s screen icon Marilyn Monroe and later celebrities such as Cindy Crawford and Madonna. The wearing of a labret or stud in this position, known as a 'Monroe Piercing', had become popular in recent years.