Marriage

Among the items in the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum relating to marriage are those that show the married status of the wearer, as well as those given as gifts from well-wishers. Also represented are those items exchanged as symbolic or actual economic goods as part of a dowry or bridewealth.In Norway, it is traditional for a bride to wear a silver crown hung with tinkling charms whose sound wards of evil spirits who may curse the marriage, whilst in Hungary brides wear an elaborate headdress incorporating woven strands of wheat to symbolize fertility.

Bridewealth is the payment to a bride's family from the groom and is commonly practised among agricultural or pastoral patrilineal societies. In Fiji a man who asks a girl's father for hand in marriage ought also to offer him a whale-tooth, an ancient symbol of status and wealth. In both the Philippines and parts of Central and South America the groom traditionally presents his bride with thirteen blessed gold coins that act as a promise of faithfulness and prosperity. In Sudan and in other areas along the Nile a man must traditionally pay his wife's family in sheep or cattle, perhaps up to thirty or forty, for the loss of their daughter's labour support. Such an exchange ratifies an engagement and the bridewealth or marriage payment usually occurs alongside a dowry.

A dowry is the opposite of bridewealth – a gift from the bride-to-be and her family to the groom and his family and can include jewellery, clothing, money, household goods, and land. Although a dowry offers stability to the couple's position from which they can set up a home, it may also be considered a conditional gift: the personal property of the bride that acts as an insurance against her ill treatment or misfortune and is returnable upon divorce or bereavement.

Much of marriage clothing and ornament is associated with the woman and may simply be worn on the wedding day as part of a ritual celebration. Among both Hindu and Muslim communities, the bride will often have her feet and hands painted with temporary henna designs during the 'Mehndi night' on the eve of the ceremony. In Norway, it is traditional for a bride to wear a silver crown hung with tinkling charms whose sound wards of evil spirits who may curse the marriage, whilst in Hungary brides wear an elaborate headdress incorporating woven strands of wheat to symbolize fertility.

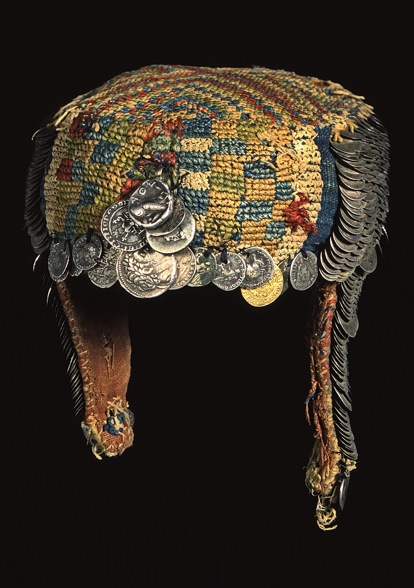

Bride's money hat from PalestineIn contrast, some items may be intended for use beyond the wedding day itself. The care and craftsmanship that went into Guajarati marriage costumes for example makes them cherished garments that may be passed on to future generations as heirlooms. According to the custom of the Nayar people of Kerala in India, the bride is presented with a tray of auspicious items relating to fertility. Some of the items are to be used in her new home (rice, a candle wick), whilst others are for her continued personal adornment – a rouge box, coconut flowers, a loincloth, and bell-metal mirror. Among the gifts a Senufo bride from the Ivory Coast receives from her family at marriage is a large pottery jar (funjoho). The jar contains a brass chameleon pendant (an important, protective charm) that she can only wear once married, and from then on the jar is used to store water for use in her new familial home.

Bride's money hat from PalestineIn contrast, some items may be intended for use beyond the wedding day itself. The care and craftsmanship that went into Guajarati marriage costumes for example makes them cherished garments that may be passed on to future generations as heirlooms. According to the custom of the Nayar people of Kerala in India, the bride is presented with a tray of auspicious items relating to fertility. Some of the items are to be used in her new home (rice, a candle wick), whilst others are for her continued personal adornment – a rouge box, coconut flowers, a loincloth, and bell-metal mirror. Among the gifts a Senufo bride from the Ivory Coast receives from her family at marriage is a large pottery jar (funjoho). The jar contains a brass chameleon pendant (an important, protective charm) that she can only wear once married, and from then on the jar is used to store water for use in her new familial home.

Rings play an important role in many unions of marriage. The practice of placing the ring on the fourth finger of the left hand (now commonly spoken of as the 'ring finger') was recorded in Roman times although the story that this was done because the vein in that finger was said to lead directly to the heart – the symbol of love – is probably a later invention. In Chile both the bride and groom exchange gold bands upon their engagement. These are worn on the right hand until the day of the marriage when they are switched to the left hand. In the Greek Orthodox Church this custom is reversed.

In Western Europe and America the jewellery industry had a large part to play in creating wedding ring exchange traditions, in particular fixing the precedent of a diamond engagement ring for women (signifying the groom's ability to pay as well as his love). In the 1920s jewellers introduced the idea of a male engagement ring although this did not take off. It remained customary for the bride alone to be given a ring that was blessed by a priest until the late 1940s when jewellers tried to target men again, this time introducing a male wedding ring. Advertisers gave these rings masculine, powerful names such as the Major', the 'Stag' and the 'Pilot' to try to break don the social conceptions that linked jewellery to femininity and this time the idea received an enthusiastic response. The 'double ring' ceremony has now become widespread across the world. In recent years there has also arisen a fashion for tattooed 'rings' around the finger, to replace metal ones, as permanent symbols of the commitment and union of marriage.