Tattooing

When we think of body art we often think of decorated skin. Skin is the body's largest organ. It is also the primary physical barrier between our inner selves and our external environment. In this way skin provides the ideal interface via which we can either protect ourselves from the outside world or communicate with it and tattooing is a primary way of doing just that. Tattoos can be aesthetic or functional but they are nearly always provocative and are often met with open mouths, averted eyes or frowns, surprise, curiosity or disgust, and their bearers are often judged or misjudged.Tattoos can provide an effective non-verbal way of communicating deeds, talents, travels, pilgrimages, personal characteristics and social, religious, familial or national pride and affiliation.

Tattooing involves the penetration of the skin to stain the subcutaneous tissue permanently with colour. The word derives from the Polynesian word 'tatau' meaning, 'to strike' or 'to inflict wounds'. The Arabic word daqq has the same meaning and both words refer to the sound made by positioning a sharp-pointed tool dipped in pigment – often made of tiny bones, thorns or splinters of wood – on the skin and tapping it with a small mallet or hammer. In the tattoos were also created by cutting the skin with a sharp stone or piece of glass, then rubbing pigment in to the wound. In Inuit culture, it was known to literally 'stitch' a tattoo by sewing a pattern into the skin using coloured thread. In contemporary societies, the most common method of tattooing is with an electric needle.

Both sexes paint their bodies Tattow, as it is called in their language, this is done by inlaying the Colour of black under their skins in such a manner as to be indelible. Some have ill design'd figures of men, birds or dogs, the women generally have this figure Z simply on ever[y] joint of their fingers and toes.

Captain Cook's journal, Tahiti, July 1769

It is often thought that tattooing was only 'discovered' in the West after Captain Cook's travels in Polynesia in the late 18th century but in fact this was more of a 'rediscovery'. Before Cook, the practice known in Europe as 'pricking' had a ancient global heritage; bodies preserved through mummification and intensely dry or cold conditions retain much of their skin and mummies of Nuba women dating to 4200 B.C. show evidence of tattoos on their abdomen. Another mummified man found in Siberia around 2500 years old had mythical beasts tattooed on his hand.

The motivations and meanings behind tattoos are as varied as the people who get them and the collections at the Pit Rivers Museum serve to highlight just some of these.

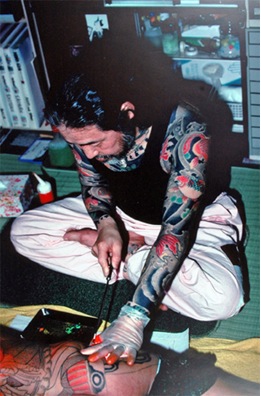

HoriyoshiTattoos can be linked to transition from one stage of life to another. They can form part of an initiation that marks the passage of boyhood to manhood or from girlhood to womanhood through the experience of pain and the transformation of both the inner and outer self. For some cultures, tattooing is necessary to establish humans as valid social beings. The Roro people of Central Province, Papua New Guinea describe an un-tattooed person as 'raw', comparing him to uncooked meat. Among some Naga groups women were tattooed behind the knee when they married and in today in Western societies some brides and grooms opt for tattooed bands around their 'ring fingers' in place of a metal ring as a sign of their union. In death too tattoos have their place; they may take the form of an 'in memoriam' tattoo to keep the memory of the deceased alive or, as in Hawaii where mourners are receive special tattoos of dots and dashes on the tongue, they may be a way of inviting physical pain to mirror or overcome the pain of grief.

HoriyoshiTattoos can be linked to transition from one stage of life to another. They can form part of an initiation that marks the passage of boyhood to manhood or from girlhood to womanhood through the experience of pain and the transformation of both the inner and outer self. For some cultures, tattooing is necessary to establish humans as valid social beings. The Roro people of Central Province, Papua New Guinea describe an un-tattooed person as 'raw', comparing him to uncooked meat. Among some Naga groups women were tattooed behind the knee when they married and in today in Western societies some brides and grooms opt for tattooed bands around their 'ring fingers' in place of a metal ring as a sign of their union. In death too tattoos have their place; they may take the form of an 'in memoriam' tattoo to keep the memory of the deceased alive or, as in Hawaii where mourners are receive special tattoos of dots and dashes on the tongue, they may be a way of inviting physical pain to mirror or overcome the pain of grief.

In many instances, tattoos are protective. In war a tattoo can act as armour, as in the 'stop bullet' tattoos worn by groups in Burma or, in the case of the elaborate facial moko worn by Maori warriors, it can intimidate and distract enemies instead. Tattoos may also be employed to prevent illness, such as the Berbers' tattoo against rheumatism or the facial tattoos found from Egypt to South Africa designed to combat eye disease and headaches. There is some medical proof that the small wounds caused by the tattooing process do indeed strengthen the immune system. The tattooing ritual can be just as important in ensuring the tattoo's efficacy: in Arab cultures, the Koran is often recited as the tattoo is applied and the pigment itself acquires magical strengthening qualities if mixed with the milk of a nursing mother.

Tattoos can provide an effective non-verbal way of communicating deeds, talents, travels, pilgrimages, personal characteristics and social, religious, familial or national pride and affiliation. Though perceived as explicit and 'readable' to the bearer and those familiar with them, such tattoos can be alien to others and misunderstood; Mesoamerican cultures tattooed images of their deities on their skin but the Spanish conquistadors who arrived in the 16th century had never seen tattoos before so they believed they were the work of the devil.

In more recent times, a tattoo can function as the ultimate symbol of gang membership. These often coded statements of family histories, convictions, conquests and skills – some recognised symbols include teardrops under the eye and spider webs on the elbows – have their origins in the punitive tattoos used throughout history to mark someone as an outcast or as someone else's property. The tattooing of slaves in ancient Rome, of criminals in Japan and China, of convicts transported to Australia in the 18th and 19th centuries, and of Jews in Nazi concentration camps – these were all intended as a denial of personhood. If such people survived, such marks testified to their ordeal. In prison, tattooing was (and is) done illegally to provide inmates what has been denied them – autonomy and identity. In the notorious Russian gulags for example, abdominal tattoos showing Lenin and Stalin as pigs with swastikas were common as extreme displays of defiance and protest.

Today the tattoo is declining in some parts of the world but thriving in others. For example, the women of the Ainu, an ancient and isolated community living on the island of Hokkaido in Japan, traditionally wore a distinctive blue 'moustache' tattoo. Today many Ainu women have married into the Japanese population and are glad they do not have to undergo the painful procedure that so drastically marks them apart from the Japanese. On the other hand in Polynesia, where the grip of colonialism has retreated in the past fifty years, there has been a revival of tattooing alongside other indigenous arts and crafts. In Europe and the USA tattoos became a topic of interest among anthropologists and criminologists in the mid-19th century. They remained a generally lower-class phenomenon attributed to sailors, carnival performers and miscreants until a huge cultural shift in the 1960s. Body arts such as tattooing, piercing and hairstyles became ways of affirming identities associated with new social movements such as feminism, sexual liberalism, punk, Goth, and neo-tribalism.

By crossing class boundaries, tattoos have become more acceptable today, even though they may still prove a hindrance to employability or some aspects of social life. Whether its David Beckham's latest addition to his growing collection of body art, or the next Hollywood star getting tattooed with 'permanent' eye-liner or lipstick, celebrities – the new social élite –are fuelling tattooing's new-found popularity.