Scarification

Scarification or cicatrization is an invasive way of permanently marking the body through cutting (or even branding) the skin, and manipulating the healing process. The scars (cicatrices) that remain can form raised lumps known as keloids. These are often created in series to form complex and delicate patterns over large areas of skin. Scarfication was most widely practised in Africa and among Australian Aboriginal groups not incidentally because the other way of permanently marking the skin – tattooing – is not as effective on dark skin.Scarification or cicatrization is an invasive way of permanently marking the body through cutting (or even branding) the skin, and manipulating the healing process.

It is possible that Aborginal Australians pactised ritual scarification many thousands of years ago. Unlike shaped bones and shaped teeth, skin rarely survives in the archaeological record but the artistic output of many ancient cultures helps provide clues as to the long history of scarfications: many of the human figures in the prehistoric (8000–5000 BC) rock paintings found in the Tassili n'Ajjer mountain range in the Sahara show markings that may well represent scarification, and Olmec stone scultptures dating from around 1000 BC found at Villahermosa in Mexico feature incisions on the face and shoulders.

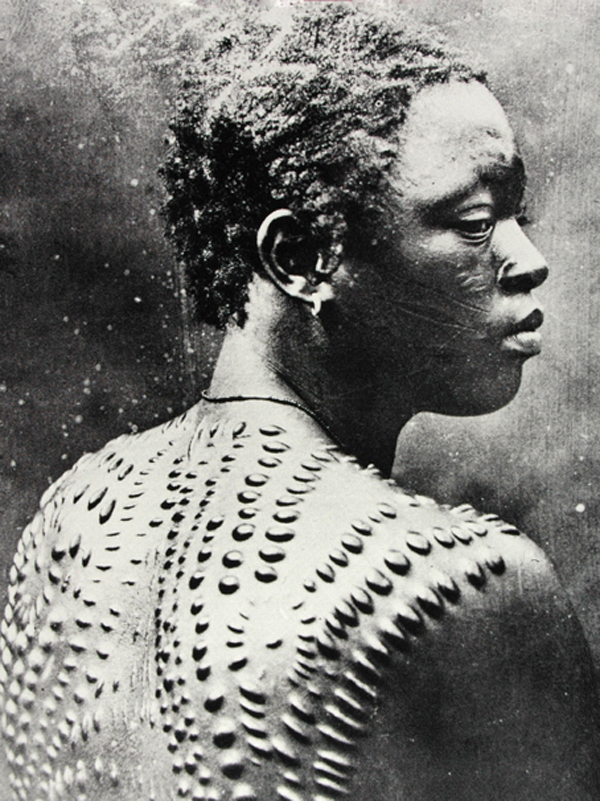

Photographer unknown, courtesy of Allen F. Roberts and the Central Archives of the White Fathers (Missionaries of Our Lady of Africa), Rome.The forms of scarification still found around the world today can vary greatly in appearance depending on the technique used. Cutting along the skin with a metal, glass or stone tool leaves 'flat' scars, whereas rounded wounds are made by raising portions of skin with a hook or thorn then slicing it across with a blade. Different effects are created by either rubbing the wound with ink, 'packing' it with clay, ash or even gunpowder to create rasied keloids, or forcing it to remain open by keeping the skin either side pulled taut to form a permanent gouged scar. Although such extreme forms of bodily decoration might seem alien to outsiders, scarification as practised along traditional lines by experienced hands has a serious ritual purpose connected to social systems and cultural beliefs. As an act of self-mutilation it cannot be regarded separately from tatooing, piercing or plastic surgery.

Photographer unknown, courtesy of Allen F. Roberts and the Central Archives of the White Fathers (Missionaries of Our Lady of Africa), Rome.The forms of scarification still found around the world today can vary greatly in appearance depending on the technique used. Cutting along the skin with a metal, glass or stone tool leaves 'flat' scars, whereas rounded wounds are made by raising portions of skin with a hook or thorn then slicing it across with a blade. Different effects are created by either rubbing the wound with ink, 'packing' it with clay, ash or even gunpowder to create rasied keloids, or forcing it to remain open by keeping the skin either side pulled taut to form a permanent gouged scar. Although such extreme forms of bodily decoration might seem alien to outsiders, scarification as practised along traditional lines by experienced hands has a serious ritual purpose connected to social systems and cultural beliefs. As an act of self-mutilation it cannot be regarded separately from tatooing, piercing or plastic surgery.

The main point of African scarification is to beautify, although scars of a certain type, size and position on the body often indicate group identity or stages in a person's life. Among the Dinka of Sudan facial scarification, usually around the temple area, is used for clan identification. In southern Sudan Nuba girls traditionally receive marks on their forehead, chest and abdomen at the onset of puberty. At first menstruation they receive a second set of cuts, this time under the breasts. These are augmented by a final, extensive phase of scarring after the weaining of the first child, resulting in designs stretching across the sternum, back, buttocks, neck and legs. Clearly Nuba scarifiation is determined by social status and maturity, and is perceived as a mark of beauty, but it can also act as preventative medicine: scars above the eyes are said to improve one's eyesight, those on the temples are said to releive headaches, and a four-pointed star near the liver protects against hepatitis.

In the context of the cultural traditions of the Dinka and Nuba, the individual has liitle in the way of choice in the matter of scarification. Undergoing the ordeal and having the 'right' marks is the only way to be fully recognised, desired or valued within a paritcular culture. The idea of socialization or 'humanization' through marking is evident in the philosophy of the Bafia people of Cameroon who say that withour their scarifications, they would be indsitnguishable from pigs or chimpanzees.

Elsewhere in Africa, scarification is done for other reasons. The Ekoi (Ejagham) of southeast Nigeria believe that the scars on their bodies will serve them as money on their way to the place of the dead. Suri men of Ethopia scar their bodies to show they've killed someone from an enemy tribe, one group for example cutting a horseshoe shape on their right arm to indicate they've killed a man, and on their left for female victim. In contrast, neighbours of the Suri, in Ethiopia's Omo valley, the Mursi, practise scarification for largely aesthetic reasons. Both men and women create swirling dotted patterns on their bodies that may not necessarily mean anything but which attract the opposite sex and enhance the tactile experience of sexual relations.

Pain and blood can play a large part in the scarification process to determine a person's fitness, endurance and bravery. This is especially the case in puberty rites since a child must prove they are ready to face the realities and responsibilities of adultthood, in particular the propect of injury or death in battle for men and the trauma of childbirth for women. This transformative element of many scarification processes can be linked to the real physiological experience; the pain sensation and release of endorphins can result in a euphoric sate conducive to spirtual attunement.

Traditional scarification has declined in Africa, Australia and elewhere since the 20th century due to health concerns and politico-cultural changes. The Ivory Coast for example is one of many modern African governments to have banned the practice as 'anti-patriotic tribalism'. Conversely, since the 1980s, scarification and branding have achieved growing cult status among certain groups – especially 'Modern Primitives – in Europe and the USA. Modern methods include laser branding and cold branding, which uses extremely cold liquid nitrogen rather than heat to mark the skin. The greatest difference in these practices is that for latter-day adherents such choices are freely made. Often they are not statements of belonging or beauty as before, but rather a rejection of belonging and mainstream society. Today scarfication may less about attractiveness or endurance and more to do with simply being radical.