Japanese irezumi

Tattooed Samurai, Japan, 1844–1874

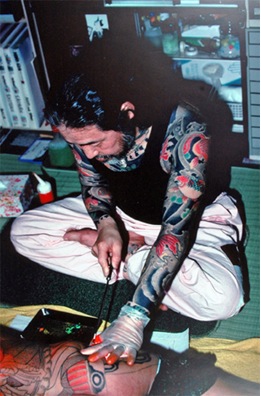

Horiyoshi, tattoo master, Japan, 1990s

Tattooing has had a colourful and fluctuating history in Japan, in all senses of the word.

Founding collection; 1980.28.8Believed to date back several thousand years, full-body tattooing in Japan was regarded as an art form, known as irezumi. The intricate and expansive designs acted as a status symbol and also carried religious significance. In China by the 7th century tattoos had become used as a punishment to stigmatize people and these negative connotations spread to Japan.

Founding collection; 1980.28.8Believed to date back several thousand years, full-body tattooing in Japan was regarded as an art form, known as irezumi. The intricate and expansive designs acted as a status symbol and also carried religious significance. In China by the 7th century tattoos had become used as a punishment to stigmatize people and these negative connotations spread to Japan.

A codified system of tattoo markings was developed to identify criminals and outcasts on their arms and foreheads. However, by the 17th century other forms of punishment replaced tattooing in Japan and ex-convicts began reclaiming their bodies by covering up or embellishing their tattoos with more elaborate and decorative designs.

The revival of tattooing was boosted by the development of woodblock printing. This print comes from the main artistic genre of woodblock printing known as ukiyo-e. Popular subjects for the prints were scenes from kabuki theatre, a traditional form of Japanese dance-drama. The artist Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865), who adopted the name Toyokuni III in honour of his master in 1844, was one of the most popular, successful and prolific woodblock designers in 19th century Edo (Tokyo). He created up to 25,000 artworks, around 60% of which feature kabuki characters. Many kabuki plays centred on the aspirations and adventures of the drifters in society, in particular Suikoden ('honorable bandits'), such as masterless samurai (ronin), gangsters, gamblers, outlaws and thieves, and many of them had tattoos. In this way, prints like this helped popularise tattoos among the ordinary urban classes.

From an photograph taken by Professor Joy Hendry in 1991Toyokuni made this print in 1863 when he was 78 years old. It features four tattooed samurai fighting amongst one another. The actors can be identified clockwise from the top right as: Nakamura Shikan IV, Ichimura Kakitsu IV, Bandō Hikosaburō V, and Ichikawa Kodanji IV. The latter has extensive cherry blossom tattoos, a symbol often associated with the way of the samurai; just as the cherry blossom is beautiful yet fleeting, so does the samurai have to live life to the full amid the imminent threat of death. The print is in fact the central part of a triptych, a set of three panels featuring ten Suikoden in all, some of whom carry katana swords, the archetypal weapon of the samurai. The scene is from an imagined (mitate) performance, not an actual play.

From an photograph taken by Professor Joy Hendry in 1991Toyokuni made this print in 1863 when he was 78 years old. It features four tattooed samurai fighting amongst one another. The actors can be identified clockwise from the top right as: Nakamura Shikan IV, Ichimura Kakitsu IV, Bandō Hikosaburō V, and Ichikawa Kodanji IV. The latter has extensive cherry blossom tattoos, a symbol often associated with the way of the samurai; just as the cherry blossom is beautiful yet fleeting, so does the samurai have to live life to the full amid the imminent threat of death. The print is in fact the central part of a triptych, a set of three panels featuring ten Suikoden in all, some of whom carry katana swords, the archetypal weapon of the samurai. The scene is from an imagined (mitate) performance, not an actual play.

As well as wearing elaborate make-up, wigs and costumes, the actors often painted additional tattoo designs on their skin for a performance. From the 20th century until the present, the effect s achieved with a niku-juban, a flesh-coloured nylon body stocking painted with tattoo designs.

More than one hundred years later, tattooing is still thriving in Japan although individual Western and neo-tribal designs are becoming more popular than the traditional sprawling designs. Traditional irezumi is still practised by specialist master tattooists, such as Horiyoshi, shown here tattooing a client around 20 years ago. He belongs to a dynasty of Horiyoshi tattooists (the affixation hori means 'to engrave' or 'carve') who use a combination of old-fashioned hand-needles and electric tools, and his son is continuing the craft. However a typical full body suit, covering the arms, back, upper legs and chest, is painful, time-consuming and expensive, requiring up to five years of weekly visits and costing more than £15,000.