See Part 2 for remainder of this ...

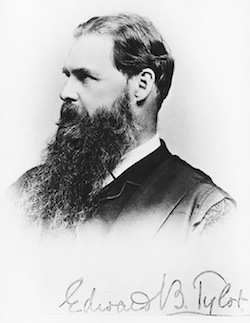

Edward Burnett TylorNote

Edward Burnett TylorNote

Megan Price worked on the Relational Museum project for six months between April and October 2003. During this time she mostly researched Tylor and his collection including contacting many of the Tylor (indirect) descendants. Unfortunately Megan did not leave a full narrative account of the man and his collection when she left the project. This narrative account therefore includes all of Megan’s research, and some research by Alison Petch. Almost everyone who worked on the ESRC-funded ‘Relational Museum’ project did some research on Tylor’s collections and this page is hopefully a summary of all of their contributions (marked as appropriate with the source). Note that where it says ‘pers. comm.’ for Megan Price this refers to information taken from her notes. Most of the information obtained from newspapers etc of Tylor’s day was provided to Megan by Chris Tylor, one of our hero’s descendants and we owe him thanks for providing copies of these. In addition, since this was put on line in 2012 John Young from Wellington in Somerset sent some comments on the text, comments such as this are added in parenthesis.

Contents

Preface

1. Introduction

2. Tylor and his life -- 2.1 Early life 2.2 Private life 2.3 Tylor’s travels 2.4 Professional life (see on to section 3 as well with related discussion) 2.5 Tylor’s time-line 2.6 Tylor’s last years and death

1. Tylor is agreed to be an important figure in the early history of anthropology as a discipline:

Edward Burnett Tylor, ... near his peak of his reputation and influence as the leading British anthropologist of the nineteenth century ...’ [Stocking, 1995: 3]

‘... Tylor emerged as the pre-eminent British anthropologist of the later nineteenth century ...’ [Stocking, 1995: 11]

This paper will consider him in relation to his collection and will therefore only lightly deal with the wider aspects of his anthropological career.

The more I have researched Tylor and the Pitt Rivers Museum [PRM] the more I think it is far easier to see him in the same relation to the museum that, say, the Professors of Social Anthropology at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology have [had] than it is to see him as a key member of museum staff. His primary role was Keeper of the Oxford University Museum (that is, effectively administering the parent body) and providing academic teaching on the subject of anthropology in the University; he was never responsible for the day to day workings on the Pitt Rivers collections / museum.

Whilst his writings often refer to particular kinds of objects, they relatively rarely discuss objects which can be identified as forming part of the PRM, even after 1884. Objects are often merely used as illustrations of wider points, not usually connected with material culture itself but often as illustrations of the evolution of man etc. Tylor more often discusses, in his publications, topics of more specifically social anthropological interest, such as how religion developed, or the particular social function of a tradition. This lack of real engagement with the museum and the objects it contains has been remarked by others. Henry Balfour became increasingly sick of the often repeated idea held by people outside the Museum that Tylor had been a key player in the early history of the museum (see on, and also Frances Larson’s page on Balfour). His irritation seems to be me to be just and Tylor’s role seems often to have been misjudged or overestimated. This, I think, is because it is confused with his role in the early development of social anthropology which Stocking and others have argued was pivotal.

However, it is clear that Tylor did have some involvement with the early history of the museum. With Moseley he took responsibility for the transfer of the Pitt-Rivers Collection to Oxford from the South Kensington Museum. Both men seem to have supervised Walter Baldwin Spencer in this task to judge by Spencer’s written memories (see on), but, of course, Spencer was working directly for Moseley, not Tylor. Balfour had the same relationship to the two men, he was employed to assist Moseley but must have worked closely with Tylor on a day-to-day basis. Tylor was the Keeper of the Oxford University Museum [of Natural History], into which the Pitt-Rivers Collection formed part. Tylor was responsible for administrative arrangements in the museum as a whole and for day-to-day management of all newly accessioned objects. For example, in the first few years items accessioned as part of the 'Pitt-Rivers Collection' were listed in the OUMNH's Annual Report, by Tylor.

It is clear that Tylor had a vital role to play in the development not only of anthropology as a discipline but in museum anthropology as an academic discipline in the UK (and elsewhere). It is perhaps for this, rather than his connection to the Museum, that he should be celebrated. However, that does beg the question of where that leaves his collection (and this project’s interest in him) and I (we?) hope the following paper answers that.

2. Tylor and his life

Tylor seems to have engendered feelings of hero-worship in many who knew him, unfortunately very few of them explain exactly why they admired him so much, limiting themselves usually to outpourings such as the following eulogy from Marett:

Great as was his science, the man himself was greater. To look as handsome as a Greek god, to be as gentle at heart as a good Christian should, and, withal, to have the hard, keen, penetrating intelligence of the naturalist of genius—this is to be gifted indeed; or, as they would say in the Pacific, such as man has mana. [Marett, 1936: 8]

Hopefully this paper will give a sufficiently wide view of his life, work and personality to at least begin to understand what made men such as Marett rate him so highly.

2.1 Early life

This account is based upon Megan and Alison’s research but also upon other biographical accounts of Tylor’s life, like his 'Oxford Dictionary of National Biography' entry, Stocking’s work etc.

Edward Burnett Tylor was born on 2 October 1832 at Camberwell, Surrey. He was the fourth son [1] of six children [2] of Joseph Tylor (1793–1852) [3] and Harriet Skipper (d. 1851). Tylor’s older brother, Alfred was later a well-known geologist. [4] The family owned a brass foundry, and belonged to the Society of Friends, otherwise known as Quakers.

Tylor was educated at Grove House, Tottenham, a school run by the Society of Friends. [6] According to Godfrey Lienhardt, ‘Tylor, brought up a Quaker, could not attend a school where attendance at chapel was compulsory (as it was at ‘good schools’) and he was debarred by university regulations from ever being a student at Oxford’. [Lienhardt, 1997: JASOvol xxviii no 1: 65] Being a Quaker at this time also precluded receiving an education at other universities and he began work at his father’s foundry, at the age of sixteen. [7] It is not clear from the information I have seen how strictly the family adhered to Quaker tenets, Stocking relates that Tylor ‘seems early to have given up the distinctive Quaker dress.’ [Stocking, 1987: 157] The family business comprised a foundry in the City of London and an associated colliery, established by his grandfather in 1768, at Tylorstown in the Rhondda valley. [8][John Young has commented that colliery and village began in 1872: See: http://webapps.rhondda-cynon-taff.gov.uk/heritagetrail/english/rhondda/tylorstown.html where it states that:

Tylorstown is named after Alfred Tylor a Londoner who purchased the mineral rights of Pendyrus farm in 1872 and sunk the first colliery in the village, also called Pendyrus. In common with the majority of the valley at that time the 1847 tithe map shows only scattered farmhouses, meadows, fields and vast tracks of Oak woods. As stated the beginnings of mining in Tylorstown, and hence the beginnings of the village of Tylorstown itself date back to 1872]

In 1855 Tylor showed signs of tuberculosis and he was sent on a recuperative trip to the United States of America where he explored the Mississippi river valley for several months before going to Havana, Cuba. It was here that he met one of the most influential people in his life, Henry Christy, a fellow Quaker, on an omnibus. [9] The two men set off on a riding expedition to Mexico. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica online entry for Tylor, Christy was on his way to Mexico to study remnants of the ancient Toltec culture in the Valley of Mexico and persuaded Tylor to accompany him. According to the DNB this trip lasted four months and according to the Encyclopaedia Britannicait lasted six when they travelled ‘... in arduous and sometimes dangerous circumstances, they searched for the Toltec remains, Tylor under Christy's experienced direction gaining practical knowledge of archaeological and anthropological fieldwork.’ [John Young comments: On the length of his tour of Mexico – in Anahuac he says in the Introduction that the journey was in March, April, May, and June of 1856 and the text shows that he arrived at Vera Cruz on 12 March [p. 18] and he left Mexico in early June [p 325]. So he was just about three months in Mexico.]

Henry Christy had a great influence on Tylor and his work. Tylor acknowledged this debt after Christy died while excavating in the Dordogne in 1865 saying they were friends for ‘... ten years during which he gave me the benefit of his wide and minute knowledge, and I was able to follow all the details of his ethnological researches’. [source unclear, Megan Price pers. comm.]

According to Megan Price [pers. comm.]:

It could be said that among the first ethnographic items that Tylor collected was the chamois leather -‘a genuine ranchero costume’ that he bought to ride through Mexico (Anahuac, 1861, 168).

On his return to the UK, his tuberculosis symptoms returned and he undertook a period of convalescence at Cannes where he wrote his first book, Anahuac, or, Mexico and the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern (1861). The DNB describes it as:

‘... primarily a travelogue of his trip, but contains early indications of his later anthropological interests, particularly his concern as to whether the pre-conquest Aztec civilization of Mexico was due to diffusion, or borrowing, or whether it arose independently.’ [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36602]

An account, written by Tylor, of his early life was published in the Aberdeen University Magazine ‘Alma Mater’ when Tylor presented the Gifford Lectures [Alma Mater, ‘The Gifford Lecturer’, 22 January 1890]:

... “In the spring of 1856, I met with Mr Christy accidentally at Havana. He had been in Cuba for some months, leading an adventurous life, visiting sugar plantations ... descending into caves, and botanizing in tropical jungles, cruising for a fortnight in an open boat among the coral-reefs ... and visiting all sorts of people from whom information was to be had, from foreign consuls and Lazarist missionaries down to retired slave-dealers and assassins. As for myself, I had been travelling for the best part of a year in the United States, and had but a short time since left in the live-oak forests and sugar-plantations of Louisiana. We agreed to go to Mexico together; and the present notes are principally compiled from our memorandum books and from letters written home on our journey.” [Anahuac, p.1] This is how Mr. Tylor fell into anthropology, and the accident recalls an accident in the life of Robert Houdin, who found in the caravan of a travelling conjuror, at once a friendly guide and an education for his genius. Mr Christy caught his death of cold in a Belgian bone cave; Mr. Tylor, under compulsion of a threatening Consumption, left the business life he had begun, and, wintering abroad at Nice, or at Cannes, or at Rome, became a man of leisure with a genius for anthropology. *”It was after doing the Mexican Journals that I formed the plan of learning all that was known about the lower races of man, which proved to be a huge undertaking and though in those years it was still possible, it has now passed the limits of any one man’s industry. For some twenty years we lived the quietest of lives at Wellington, in Somerset, writing Early History of Mankind and Primitive Culture which latter, published in 1871, is just going into its third edition. Then, years afterwards, being pressed to it by Freeman, the historian, an old friend, I did the little hand-book “Anthropology”. I had wanted to put the anatomical part into the hands of a professional anatomist, but found it best to do it myself in an untechnical way clear to untrained readers. I have been amused to find the drawings of the human hand and foot (the ownership of which I leave you to guess at), compared with ape’s hand and foot, reproduced in German educational books. In 1883 I migrated to Oxford to the quasi-sinecure post of keeper of the museum, and afterwards was appointed Reader in Anthropology, by adoption becoming a member of Balliol College. In 1884, going to Montreal to preside over the Section of Anthropology, I made with Professor Moseley an interesting camping visit to the Ojibwas on Lake Huron, and afterwards the Bureau of Ethnology made an interesting excursion for us to visit the Pueblo Indians of Zuni and other tribes of Arizona and New Mexico. The Central Pacific Railway had just made it easy to visit the Zuni Indians before they became sophisticated by closer contact with white men, and it was still possible to study comparatively little changed the old life of these Indians in their fortress like dwellings of mud…

*Extracts from a letter by Dr. Tylor [original Alma Maternote, it is not mentioned who the letter was addressed to]

All of these instances are mentioned below in more detail.

2.2 Private life

In June 1858 Tylor married Anna Rebecca Fox (d. 1921), daughter of Sylvanus Fox, (1791 - 1851) and Mary Sanderson (d. 1846) of Wellington, Somerset. Both Anna and Edward came from Society of Friends families (Quakers were not allowed to ‘marry out’). According to Megan Price, they first met at Yearly Meeting. [11] Anna Fox was the only sibling in her family to marry, the children had been very protected by their parents. [Hubert Fox, Quaker Broadcloth; The Story of Joseph and Mariana Fox and the Cousinry at Wellington: 46] It seems, however according to The Society of Friends records that they both resigned from the Society in 1864. [12]

In 1858, when Anna and Edward were about to be married, Tylor is described as ‘decidedly very clever’. [Hubert Fox, Quaker Broadcloth; The Story of Joseph and Mariana Fox and the Cousinry at Wellington: 13] An impression of him, written by A.L. Humphreys in 1933, gives an idea of the way Tylor struck onlookers:

Often when taking walks with my father, Tylor would stop and talk, and when he had passed on my father would say ‘That was Dr Tylor; he is a very eminent anthropologist’ and I would wonder what on earth an anthropologist was. Tylor was a remarkably handsome man of very fine presence. Even in the London streets I have seen people turn to look at him a second time. On Sunday evenings I would often see him going up South Street to spend the evenings with Charles Henry Fox. He walked like the prince of intellect he was. [Megan Price pers. comm. quoting from When I was a Boy A.L. Humphreys, 1933. possibly page 58]

The volume Quaker Broadcloth; The Story of Joseph and Mariana Fox and the Cousinry at Wellington written by Hubert Fox gives glimpses of the private Tylor: he apparently would play tennis at a house called The Cleve in Wellington. He gave lectures at Wellington Town Hall, he apparently liked women as much as books, ‘Marion once boxed Cousin Edward’s ears, and Margery was always a little apprehensive when she was with him[. [possibly page 46] [Megan Price pers. comm.]

The Tylors had no children but Anna was devoted to him and attended most of his lectures. Stocking indicates that the Tylors probably read anthropological tomes aloud together. [Stocking, 1987: 158] Dorothy Tylor, [13] a niece of Edward Tylor, spent much of her adult life with Edward and Anna, acting as their companion, and later their executors. She died in 1954. [Megan Price, pers. comm.]

When they first married they lived in Highbury, London. [Megan Price pers. comm.] Their principal married home was in Wellington, Somerset from 1865, latterly at Linden (and according to the accession books a house called Foxdown at some point), to which Tylor retired and where he died. [John Young: Tylor moved to Wellington in 1865. When he joined Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society [SANHS] in 1862-3 his address was Ventnor, Isle of Wight, but subsequent membership lists give his address as Wellington. As Megan points out the SANHS obit seems to have forgotten that he was a member for before he went to Oxford – interestingly he rejoined in 1901.] They must have inherited Linden from Anna’s brother Sylvanus who lived there for half a century. [Hubert Fox, Quaker Broadcloth; The Story of Joseph and Mariana Fox and the Cousinry at Wellington: 45]. When they had retired there from Oxford they are described in the same volume as sitting together and playing backgammon [possibly ibid page 48] [Megan Price pers. comm. John Young pointed out that Sylvanus Fox was Anna's brother not father as previously given]

Tylor was a member of the Athenaeum Club and the Century Club, although this seems a little odd for a Quaker, who do not usually drink alcohol. He was also a member of many professional associations and institutions including the Anthropological Society (later the Royal Anthropological Institute), of which he was President and the Royal Society (of which he was a Fellow). During his lifetime Tylor belonged to the following professional clubs and societies:

Royal Society

Folklore Society

British Association for the Advancement of Science

Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society

Oxford Natural History Society

and the Royal Anthropological Institute

In other words he was a fully functioning member of the British Establishment long before he became Keeper of the University Museum. Tylor used his private contacts to further his professional career:

'Standard examples include letters accompanying gifts from family members and acquaintances who had perhaps at some point had a conversation with Tylor concerning the Museum, or were familiar with his published work, and who had happened upon an object that they thought would interest him. These letters generally reveal their writers to have had little more than a basic understanding of the meanings of the specimens they discussed, and an assumption that the objects they sent would be appreciated and understood by Tylor. Others are clearly written in response to requests for information or objects. These letters cover an extensive cultural, historical and geographical range, and provide intriguing glimpses into drawing-room conversations involving the customs of other cultures and places, including rural Britain, as the extract from Tylor’s cousin, Elsie Howard, ... ‘

[Some time ago I remember that you were interested in potatoes that have been carried in the pocket for rheumatism, so I think I will send you, in case you care to have them, these two potatoes which were given to me yesterday. They have been carried for more than three years by an old gentleman here, the master of a city company, who has the firmest belief in them, - indeed I feel rather brutal to accept them, but he said he should begin another one! (Elsie Howard to E. B. Tylor 16.4.18?? [year unknown], Tylor Papers, PRM manuscript collections).] [original draft of Brown, 2005, page 1]

The network was extended further still through Tylor persuading friends and acquaintances to ask their overseas contacts to send materials for the Museum, often with extremely positive results:

'Here are a couple of the Jain rosaries which my friend, Chester MacPherson has sent me for you from Rajkut. He says “they are very common cheap little things”, but I am told they are of the sort always used though others are known. But if they are not the sort required, I can send you as many more as you like.’ (J. Holland to E.B. Tylor, 09.01.1891. E.B. Tylor Papers, PRM manuscript collections). [original draft of Brown, 2005, ?unpublished page 9]

Tylor seems to have had a strong sense of fun and humour. He seems to have been keen to write poetry and here contributes to a poem written to Andrew Lang (a photocopy of this was given by Chris Tylor). The section written by Andrew Lang reads:

Primitive Man

He lived in a cave by the seas

He lived upon oysters and foes

He made kitchen middens of these

And ..., as a rule, upon those.

Geology’s evidence shows

He had never a pot nor a pan,

And he shaved, with a shell when he chose

T’was the manner of Primitive Man.He worshipped the rain and the trees

He worshipped the River that flows

And the Dawn, and the storm and the breeze

And bogies, and serpents and crows

He buried his Dead with their toes

Tucked up a peculiar plan

Till their Knees came right under their nose

T’was the manner of Primitive Man.His Communal Wives, at his ease.

He would curb with judicious blows,

Or, his state had a Queen, like the Bee’s,

As some other inquirers suppose,

When he spoke, it was never in prose,

But he sang in a strain that would scan,

For (at least so the theory goes)

T’was the manner of Primitive Man.Prince, proud as you ancestors prose

It was thus their journey began

And as every Darwinian knows

T’was the manner of Primitive Man.

Tylor’s (handwritten) contribution reads:

From savage commencements like these [14]

Society’s fabric arose

Developed, evolved, if you please—

But deluded chronologists chose

To declare that mankind with their woes

In B.C. 4000 began

Moses’ history of Primitive Man.But the mild anthropologist sees,

That so recent he cannot suppose,

Flints palaeolithic like these,

Quaternary bones such as those.

In Rhinoceros, Mammoth and Co’s

First period the Human began,

And Theology’s dream to expose,

Was the purpose of Primitive Man.

Note that I have read several different forms of this poem in various printed sources, most mentioning Tylor’s contribution but attributing the main poem to Lang. I am unclear what the actual status of this poem is. It seems it might have been published in ‘Ballads in Blue China’. According to http://www.bookrags.com/ebooks/3138/11.html,

the poem is entitled ‘Double Ballade of Primitive Man to J.A. Farrer’ and goes as follows:

He lived in a cave by the seas,

He lived upon oysters and foes,

But his list of forbidden degrees,

An extensive morality shows;

Geological evidence goes

To prove he had never a pan,

But he shaved with a shell when he chose, —

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man.He worshipp’d the rain and the breeze,

He worshipp’d the river that flows,

And the Dawn, and the Moon, and the trees,

And bogies, and serpents, and crows;

He buried his dead with their toes

Tucked-up, an original plan,

Till their knees came right under their nose, —

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man.His communal wives, at his ease,

He would curb with occasional blows;

Or his State had a queen, like the bees

(As another philosopher trows):

When he spoke, it was never in prose,

But he sang in a strain that would scan,

For (to doubt it, perchance, were morose)

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man!On the coasts that incessantly freeze,

With his stones, and his bones, and his bows;

On luxuriant tropical leas,

Where the summer eternally glows,

He is found, and his habits disclose

(Let theology say what she can)

That he lived in the long, long agos,

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man!From a status like that of the Crees,

Our society’s fabric arose, —

Develop’d, evolved, if you please,

But deluded chronologists chose,

In a fancied accordance with Moses,

4000 B. C. for the span

When he rushed on the world and its woes, —

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man!But the mild anthropologist,—He’s

Not RECENT inclined to suppose

Flints Palaeolithic like these,

Quaternary bones such as those!

In Rhinoceros, Mammoth and Co.’s,

First epoch, the Human began,

Theologians all to expose, —

’Tis the MISSION of Primitive Man.ENVOY,

MAX, proudly your Aryans pose,

But their rigs they undoubtedly ran,

For, as every Darwinian knows,

’Twas the manner of Primitive Man! {2}

According to http://www.tnellen.com/cybereng/blank_v.html ‘... the ballade (not to be confused with the ballad); it normally has three stanzas of eight lines and a concluding stanza or "message" called an envoy of four lines usually addressed to a "prince" or patron. The rhyme scheme is ababbcbc with the envoy rhyming bcbc; all of the stanzas have the same rhyme sounds in corresponding lines but no rhyme word may be repeated. The last line of the first stanza becomes a refrain with which each of the other stanzas ends. An amusing use of the form is in Andrew Lang's Double Ballade of Primitive Man; in the envoy, Max, instead of the "prince" or patron, is Professor Max Müller, a theorist about primitive sun-god myths, who was perhaps the poet's greatest antagonist..’ The mystery deepens however for this account of the poem is identical to that above except that it omits (and does not suggest that it has omitted) the final two stanzas above the Envoy. The mystery, and Tylor’s contribution to it, could probably only be definitively answered if the manuscript version of the Ballad of the Blue China was consulted.

An impression of how Tylor appeared to Oxford friends was given by Myres many years later:

Soon after I [Myres] came up in 1888, I was introduced ... to Dr. Tylor, and attended his lectures in the Mathematical Room in the University Museum. The audience was small, mostly ladies. ‘So many hat [sic] of women.’ he would say, counting Miss Wild separately. Mrs Tylor sat in the front row, watchful for confusion among the specimens. ‘Oh, Edward dear’ she would say, ‘last time, you said that one was neolithic.’ But she did not prevent the conflagration when he demonstrated the fire drill, and his long beard became entangled with the bow. Usually, however, he got no fire. ... Later I used to call, at Mrs. Tylor’s suggestion, and take him for a walk. One had to plan one’s route carefully, for he was liable to halt and work out some problem on the return journey, and arrive home late. He began to sleep badly and Mrs. Tylor encouraged me to look in about nine p.m. for a pipe before bedtime. He liked company as he smoked ... His thoughts tended to revert to the past ... of his travels and the Mexican barbers who offered you the choice of ‘the steel or the stone.’ If you were wise, you chose ‘stone’ and had the further choice of newly flaked obsidian blades on a napkin from the back room. ... When I told him that as Professor of Anthropology he might have to be ex-officio examiner for the Diploma [in Anthropology] he was appalled: ‘I know nothing about examining. I have never been examined in my life.’ [Myres, 1953: 6-7]

There seems to have been something about Tylor and fire for here is another story (described as ‘frivolous’ by the author):

‘Tylor was lecturing on this very subject (manipulative skills) at the Royal Institution, and sought to show how the simple fire-drill was worked by twirling one stick against the other as nimbly as could be; but, possibly because the London atmosphere was unpropitious, nothing happened, and the lecturer seemed put out. Tyndall, who was there, offered to take on the duty, so that the discourse might continue. Instantly, fire flared up, and the audience applauded. “But, Tyndall,” said Tylor afterwards, “I don’t understand: you should have produced no more than a spark.” “I’m afraid” was the reply, “that I added the head of a lucifer match, just to cheer the thing up!” [Marett, 1936: 200]

Marett concluded about Tylor that:

‘... whereas his zeal for Anthropology never flagged to the end of his working days, it might not be altogether unfair to accuse the Pitt-Rivers collections of having taken up more than a fair share of the time that he could ill spare from delivering over sixty terminal courses of lectures, writing innumerable articles and reviews, presiding over learned societies, organizing courses of academic instruction, and so on. After twenty years’ intercourse at Oxford, one retains the impression of him as the very happiest of men, and that because he was everlastingly finding something new to play with. Sometimes it was an idea but oftener it was a toy. It might be a Tasmanian implement, that he would suddenly produce from his pocket; or it might be a Haida totem-post of such vast proportions that ... [it] could hardly get into the Museum.’ [Marett, 1936: 211]

In Haddon’s introduction to Anthropology (Thinker’s Library edition) Tylor is summarised as:

‘Dr Tylor was a tall man of imposing appearance, and his friendly, modest courtesy will never be forgotten by those who had the privilege of knowing him. ... apart from [Tylor’s] four books, his activity largely manifested itself in lectures, reviews, and addresses. His papers, even when descriptive, were always marked by a breadth of view and an endeavour to drive home the lessons to be garnered from the facts. There were few aspects of Anthropology which he had not investigated, and he enriched all those with which he dealt. He was always interested in method, and it was mainly by his efforts in this direction that ethnology could claim to be recognized as a science.’ [Haddon, Introduction to Anthropology, 1930: v-vi]

It is possible to see Tylor's religious background as a linchpin both in the development of his ideas on religion but also as a precursor to his wider attitudes and beliefs:

'... as might be expected of a Quaker, the author of Anahuac is staunchly anti-Catholic, and especially antipathetic to what he regarded as empty display in religious observance. Like nearly all students of primitive religion at the time, he was an agnostic. Lacking religious convictions himself, and prejudiced against ritual observance, his influence on the subsequent study of primitive religion acted to overvalue the intellectual and speculative component of religion (beliefs and intentions) at the expense of the physical and affective (rites and ceremonies). He cared more about creed than consolation.' [Ackerman, 1987: 77]

2.3 Tylor’s travels

As the DNB recounts: ‘[Tylor] ... was, as one commentator has noted, primarily ‘a navigator of books’. For the most part he culled his data from the reports of travellers and missionaries. He always attempted to corroborate this information and always carefully weighed the evidence according to his own common sense.’

However he did travel and here is a list of the journeys for which he obtained passport documents [information provided via Megan Price, pers. comm.]:

|

Date |

Destination |

|

1852 |

France, Spain, Italy, Gibraltar, Morocco |

|

1853 |

Switzerland, Italy, Croatia |

|

1854 |

Italy, Germany, Austria, France |

|

1855 - 1856 |

Italy, USA, Cuba and Mexico. |

|

1857 |

Germany [and France?] |

|

1858 |

Italy, France, |

|

1860 - 1861 |

France, ?Greece (spent winter in France) |

|

1862 |

Spent winter on Isle of Wight, Greece [possibly only Anna Tylor it is hard to tell from Megan’s notes] |

|

1863 |

June - September in Scotland |

|

1867 |

Switzerland and Italy [visit Swiss Lake Villages] |

|

1869 |

Switzerland |

|

1870 |

September in Cornwall |

|

1872 |

‘Abroad’ including Belgium |

|

1873 |

Took Dorothy Tylor to Lake District |

|

1875 |

Switzerland |

|

1877 |

‘Abroad’ |

|

1878 |

Brittany |

|

1879 |

Lake District |

|

1881 |

Greece, Corfu, Italy, France and Ireland |

|

?1881 |

?Turkey [it is hard to tell from Megan’s notes if this date and journey is right] |

|

1882 |

Cornwall |

|

1883 |

Switzerland |

|

1884 |

Canada (for BAAS) USA and tours New Mexico with Moseley |

|

1885 |

Holland, Scotland |

|

1886 |

North Africa, Algeria |

|

1887 |

Switzerland |

|

1888 |

Norway |

|

1889 |

Russia, Norway, Sweden, Poland and Germany, Scotland |

|

1890 |

Switzerland |

|

1891 |

Cornwall |

|

1892 |

Italy |

|

1893 |

Switzerland |

|

1894 |

Norway |

|

1895 |

Holland and Denmark, Switzerland |

|

1898 |

Switzerland |

|

1899 |

Austria, Hungary, Bosnia |

|

1901 |

France, Scotland |

|

1902 |

Switzerland |

|

1904 |

Italy, Germany |

2.4 Professional life

His professional life first began on the trip to the USA, Cuba and Mexico and was fostered by private study. Because of his religious status he was precluded from life as an academic and therefore he was forced to undertake scholarly research and writing outside an academic institution. This was more common during the Victoria era than it would later be in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Christy may have started his interest in ethnology and anthropology, and his trip to Cuba and Mexico must have fostered it. After the publication of his first book, Anahuac, Tylor began to ‘familiarize himself with the growing ethnological, linguistic, and archaeological literature, keeping numbered notebooks of his research, now located in the Balfour Library, Oxford.’ [DNB] According to Gosden and Brown [ers. comm] Tylor’s notebooks record visits that Henry Christy and he made to museums in the 1860s.

In 1862-3 Tylor joined the Somerset Archaeology and Natural History Society [Megan Price, pers. comm.] Interestingly his address was given as Ventnor, Isle of Wight so he might still have been recovering from tuberculosis. Many other well-known amateur anthropologists and archaeologists were members of the Society including Boyd Dawkins. Other people were honorary and corresponding members including Acland, and J.H. Parker (both of whom were from Oxford). By 1865 Tylor had moved permanently to Somerset. His early membership of the Society seems to have been forgotten by the time that his (very inaccurate) obituary was published in the Society’s Proceedings of 1917 (vol LXII) where he was said to have joined in 1901 but to have lectured at ‘conversaziones’ as early as 1865 or 1866. [Megan Price, pers. comm.]

After Anahuac the next ventures he made in the ethnographic field were based around the time he spent in the Berlin Deaf-and-Dumb Institute in the 1860s, which he visited to study the ‘inmates’ gesture language which they had developed on their own. He hoped to discover how both language and culture began in humans. His second book, Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization (1865), is described by the DNB as beginning:

‘... with an analysis of his discoveries, is about origins and how to account for the similarity in customs and beliefs in different areas of the world.’

in 1865 he wrote his first review in The Times. [Megan Price, pers comm] In 1866 he wrote two articles, for the Fortnightly Review and Quarterly Reviewrespectively, which drew on the work of Max Müller, and in which Tylor developed his ideas about the origins of language. In 1865 and again in 1866 he made visits to Oxford (for an unknown reason). [Megan Price, pers. comm.] In 1865 he attended the BAAS meeting in Birmingham, in 1866 the BAAS meeting in Nottingham [?] and in 1868 the meeting in Norwich. In 1869 he published ‘The survival of savage thought in modern civilization’ (in the Proceedings of the Royal Institute) following the lecture on April 23rd of that year. [John Young comments with regard to Tylor's facility with languages: ‘Tylor was a foreign languages clerk’ [EE Evans-Pritchard Social Anthropology p. 72] The piece in Popular Science says that he learned languages to help with his researches as many translations were inadequate. See Popular Science Monthly Volume 26 December 1884]

According to the DNB article Tylor’s main claim to fame rests on his two-volume work Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (1871). This is described by Stocking as his ‘magnum opus’ [Stocking, 1995: 3] Ackerman says:

'Spencer had been advancing evolutionary arguments for social phenomena in the 1850s, so that although it is tempting, it is not accurate to understand the burst of evolutionary philosophizing in the third quarter of the century as directly and exclusively influenced by Darwin. John Burrow has put it neatly, "In this context, Darwin was undoubtedly important, but it is a type of importance impossible to estimate at all precisely. He was certainly not the father of evolutionary anthropology, but possible he was its wealthy uncle." Certainly the most important example of evolutionary anthropology was Tylor's Primitive Culture (1871) which is regarded with justice as the founding document in modern British social anthropology.' [Ackerman, 1987: 77]

According to Stocking it was continually in print for over twenty years after publication. In that same year he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1871 Tylor attended the BAAS meeting in Edinburgh but he was not well and had to give one of the evening lectures. [Megan Price, pers comm.]

Shortly after the publication of Primitive Culture Tylor wrote a review (1872) of the work of the Belgian sociologist and statistician Adolphe Quetelet. Quetelet's influence became clear in a two-part article that Tylor wrote for the Contemporary Review in 1873 entitled ‘Primitive society’. In 1873 he lectured at the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society on the Primitive Social Condition of Man. In 1876 on March 22 he lectured to the London Institute, and again in January of 1877. On November 15 1878 he lectured to the Bath Literary and Philosophical Society on The beginnings of Exact Knowledge. On March 14 1879 he lectured at the Royal Institution on the history of games, later in that year he attended the British Association meeting in Sheffield where he gave an address to the Anthropological Section on Man’s Antiquity. In 1880 he gave the Anthropological Institute’s Anniversary Address. In 1881 he gave a talk at the London Institute on Problems in the History of Civilisation and on January 25 of the same year he gave the Anniversary Address to the Anthropological Institute again in which he discussed the ‘Pitt Rivers collection’. In 1882 he gave another lecture to the Royal Institution on The History of Custom and Belief. [Megan Price, pers. comm.] In 1889 he published a further article in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute called ‘On a method of investigating the development of marriage’. [DNB]

The DNB describes his later publishing life thus:

He was instrumental in drafting the first edition of the Royal Anthropological Institute's Notes and Queries on Anthropology for the Use of Travellers and Residents of Uncivilized Lands (1874), and contributed eighteen sections (the largest number). He also wrote eleven articles for the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which was published between 1875 and 1887. Tylor's last book, Anthropology: an Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization, published in 1881, was the first introductory textbook on the subject and provided a survey of what was then known in the field. Over the winters of 1889–90 and 1890–91 Tylor delivered two series of ten lectures each at the University of Aberdeen, some of the first Gifford lectures. [15] He spent the next ten years preparing them for publication; however the intended book, to be entitled ‘The natural history of religion’, was never published.

Regarding Tylor’s contribution to Notes and Queries, Urry believes that the production of a ‘fieldwork questionnaire’ in 1871 was mainly due to members of the old Ethnological Society, [16] ‘Tylor, Lane-Fox, Lubbock, Evans and Galton, men who saw anthropology as a natural science among natural sciences. Anthropology was for them a science, and information on other races was to be collected by scientific methods.’ [Urry, 1972: 46] Urry recounts how the term ‘culture’ (used for one of the sections of the first edition of Notes and Queries ‘reflected the influence of Tylor and he contributed the largest number of parts; eighteen in all. ... The sections written by Tylor contain not only lists of questions but also specific instructions as to how to collect which types of information, with advice about objectivity. In spite of all the statements about objectivity, however, the questions posed by Tylor and others reflected the concerns of their age, both in scope and the number of questions asked.’ [Urry, 1972: 47]

In 1872 Tylor actually undertook a short period of ‘participant-observer’ fieldwork when he became interested in spiritualism. As Tylor himself explains:

‘In November 1872, I went up to London to look into the alleged manifestations. My previous connexion with the subject had been mostly by way of tracing its ethnology and I had commented somewhat severely on the absurdities shown by examining the published evidence. ...’ [unpublished ms in PRM ms collections, quoted in Stocking, 1971: 91]

During the course of a month or so Tylor attended many seances with different spiritualists (one of them ‘recommended’ by Pitt Rivers!) Tylor concluded:

‘What I have seen and heard fails to convince me that there is a genuine residue. [I]t all might have been legerdemain, & was so in great measure except that legerté is too complimentary for the clumsiness of many of the obvious impostors. ... I admit a prima facie case on evidence, & will not deny that there might be a psychic force causing raps, movements, levitations etc. But it has not proved itself by evidence of my senses, and I distinctly think the case weaker than written documents led me to think. Seeing has not (to me) been believing, & I propose a new text to define faith “Blessed are they that have seen, and yet have believed.”’ [unpublished ms in PRM ms collections, quoted in Stocking, 1971: 100]

At some point during this period (I assume) Tylor started to take an interest in general education, providing classes at the local Wellington Literary and Scientific Institution. An article in the Wellington Weekly News of January 10 1912 describes:

The scientific side was represented chiefly by a number of lectures given during the winter months. Dr Tylor on several occasions lectured for the Institute in what was then the Town Hall—... In these lectures, dealing with such subjects as “Colour” and “Sound” the demonstrator was almost invariably the late Mr Robert Knight, and much of the apparatus used in the illustrative experiments was made by Mr Knight in his workshop ...

Tylor’s publications had obviously gained him the admiration of his peers and this proved sufficient to earn him the degree of DCL from the University of Oxford in 1875. An account of the Encaenia on June 9 1875, when Tylor received his honorary degree, says:

Honorary degrees were then conferred on the Very Reverend R.W. Church ... Sir John Lubbock ... and Mr E.B. Tylor, all of whom were constrained to stand in a long line along the narrow passage which led up to the Vice-Chancellor’s throne like candidates for confirmation before a Bishop. ... The University honours herself in granting her honours this year to the gentlemen whom she has selected for degrees. The almost new and nameless science of comparative research into the history of human institutions is recognized in the persons of Sir John Lubbock and of Mr Tylor. Both have helped to endow Englishmen with new interests, with new knowledge, with an invaluable instrument and guide in the formation of opinion. [Daily News, June 10 1875, ‘Encaenia at Oxford’]

The Times account of the same occasions states:

In solemn silence the Regius Professor of Law presented each of the candidates for an honorary degree: ... and Mr Tylor, famous for his researches into the science of the origin of man. Each of these, as he was presented, was received with a flutter of feminine interest and passed to his seat. [The Times, June 10 1875 ‘Commemoration at Oxford’]

The Tylors stayed with the Rollestons during this visit. [Megan Price, pers. comm.] This recognition was confirmed by paid employment from the same University from 1883.

Tylor was to some degree, it appears, the nineteenth century equivalent of a ‘media celebrity’ (although, I suspect a highbrow version), who courted, or at least attracted, controversy. An article in Punch dated February 10 1877 writes:

‘An appeal for the alphabet (From an alarmed conservative)

It is unfortunate that a language of such power and prospects as the English should have so disordered an Alphabet, which has been thrown into utter confusion by the attempt to keep up English and French spelling in it at once. At present two millions of English-speaking children come up for education annually, and waste from one to two years of their educational life in mastering this absurd puzzle, the cost of maintaining which can thus hardly be less than ten to twenty millions sterling a year, which would be saved by the use of a rational Alphabet.” E.B. Tylor, on the Philosophy of Speech.

In response to which the anonymous author burst into verse:

Reform our English Alphabet? Good lack!

What won’t these revisionists attack?

I fondly fancied that the A.B.C.

Was the fixed symbol of simplicity,

The one thing changeless, certain, strong and stable,

Midst Innovation’s universal Babel.

Here TYLOR comes that A.B.C. to shake,

And prove our spelling one immense mistake ...

Against this E.B. Tylor’s sly attack

Let all Conservatives stand back to back,

And fight for our time-honoured A.B.C.—

I’m very sure its good enough for me.

In 1881 Tylor resigned the position of President of the Anthropological Institute and said:

'In now resigning this chair to an already tried and successful President, General Pitt-Rivers, it may not be inappropriate for me to express a hope that his Museum of Weapons, which illustrates so many problems in his History of Civilisation, and has been already in its collector's hands so fertile a source of new ideas, may in some shape become a national institution. It is not a small duplicate of the national ethnographic collection of the British Museum, but something of different nature and different use. It is not so much a collection as a set of object-lessons in the development of culture, and the student whose mind is unprepared to visit intelligently the British Museum collection, may gain by preliminary study of the Pitt-Rivers collection an idea of development which will be a natural framework for further knowledge. He will know better what to look for in the vast galleries of the British Museum, and how to appreciate its meaning when he sees it...'

‘[A]s a result of a formal petition on his behalf by twenty Oxford professors, Tylor gave two public lectures on anthropology at the university in February 1883 which attracted large audiences, [Stocking 1987: 264] [Chapman, 2000: 501] and when the Keeper of the University Museum (Henry Smith) died early that very month, Tylor was chosen to replace him’.

An account of these lectures was given in Science:

Tylor's lecture at Oxford - On Feb. 15 and 21, Prof. E.B. Tylor lectured at the University museum, Oxford, upon anthropology. The occasion was the installment of a museum of civilisation, the nucleus of which is the Pitt-Rivers collection, previously mentioned in Science. The speaker first drew attention to the fact that the theory of development has had its own evolution parallel with the progress of knowledge. Pritchard recognized the descent of mankind from one pair, whom he considered to have been negroes; and as we have been able to reconstruct the ancestry of the horse, Huxley leads us to hope that we may some day discover the fossil pedigree of his rider.

Mr Tylor next spoke of the approach which cranioscopy is making to an exact science, drawing his illustrations from the crania of the British barrows, and other localities of undisturbed population. Comparative philology, properly understood, may tell its story in perfect accordance with anatomy. The blended parentage of the Fijians is heard in their speech, as it is seen in their faces. The cross-section of a single hair, examined microscopically by Pruner's method, shows it circular, or oval, or reniform; its follicle curvature may be estimated by the average diameter of the curls, as proposed by Moseley; its coloring-matter may be estimated by Sorby's method. This examination enables one to judge in what division of the human species to classify its owner. Climate, albinism, 'Addison's disease,' and other natural causes in their relation to race-color, are carefully considered.

It is upon the evolution of civilization, however, that Mr Tylor is most happy, a subject to which he has devoted the most of his life. The last portion of the addresses, therefore, is devoted to the unfolding of several phases of social life in their relation to race and history. - (Nature, May 3) [Science, volume 1, no 18, June 8th 1883, p525:]

Tylor's lectures at Oxford. - The concluding portion of Dr. Tylor's lectures on anthropology, delivered in the Oxford museum in February (see i. 1055), is devoted to the history of the growth of practical art. 'In considering the claims of anthropology as a practical means of understanding ourselves, we have to form an opinion how the ideas and arts of any people are to be accounted for as developed from preceding stages. To work out the lines along which the process of organization has actually moved, is a task needing caution. A tribe may have some art which plainly shows progress from a ruder state of things: and yet it may be wrong to suppose this development to have taken place among themselves; it may be an item of higher culture, that they have learned from sight of a more advanced nation. It is essential, in studying even savage and barbaric culture, to allow for borrowing.' Illustrations are given by Dr. Tylor of this borrowing, one of which is quite amusing. The later Danish travellers among the Eskimo enter very minutely into the description of the tools and dress of these people, before contact with Europeans, meaning the post-Columbian voyagers; but, unwittingly in many instances, they are describing fashions and forms borrowed from the Skraelling ancestors of these very writers a thousand years ago. Another very important point discussed in the lectures is the possibility of national degradation. Dr Tylor was the first to discover, after the battle between the advocates of 'degradation' and those of evolution, that both were right, and that a proper view of human history must include both vicissitudes over and over again, and the commingling of both in every degree of complexity. Mr Tylor gives a succinct account of the formation of the Pitt-Rivers collection, now housed at Oxford, and, in commenting upon the evolution of gesture-speech, pays this tribute to our country: 'The labor and expense which anthropologists in the United States are now bestowing on the study of the indigenous tribes contrasts, I am sorry to say, with the indifference shown to such observations in Canada, where the habits of yet more interesting native tribes are allowed to die out without even a record.' With very great shrewdness the speaker discussed the subject of magic and the benefit derived from even such useless search as that for the 'lost tribes of Israel.' - (Nature, May 17) J.W.P. [Science volume 2, no. 23, 13 July 1883, p57]

According to Megan Price’s research Tylor received the proposal of a post at Oxford on 22 February 1883 and he was appointed to the Keepership on March 10 of that year. [17]

‘E.B. Tylor, for whom the first readership in Anthropology in the UK was created in 1884, and upgraded in 1896 to a personal chair, was the leading British scholar of the time in his field—ethnology was, in effect, in Max Müller words, ‘Mr Tylor’s Science’. [Howarth, 2000: 468 quoting in part from A. Kardiner and E. Preble They Studied Man (1962), 76]

He moved to Oxford on 19 September 1883. As he was the Keeper he moved into Museum House on September 22 1883, ‘a large and ornate Victorian Gothic building in the Museum grounds, dating from about 1860, soon after the completion of the University Museum, which it matched in style. It was later used to provide additional accommodation for various scientific departments, including storage space for the Pitt Rivers Museum, until it was demolished in 1954 to make way for a new Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory’. [Blackwood, 1970: 10] As Keeper of the University Museum he oversaw all new accessions to the Museum, listing them for the purposes of his annual reports under the subheadings ‘Anatomy and Zoology’ in 1884, and thereafter ‘Anatomy and Zoology’, ‘Anthropology’ and ‘Geology’ (Oxford University Gazette XIV: 475; XVI: 160).

In 1883 the University Gazettes recorded the appointment of Tylor to the first anthropological academic post in the UK. A Decree submitted in November 1883 proposing appointment of a Reader in Anthropology, with stipend of £200 a year who would lecture in each of three University terms, for not less than six weeks, once in each week. He would also lecture students for informal instruction twice each week. Any student who received informal instruction was required to give no more than £2 a term, otherwise all the lectures were open and free to members of University. [Vol. XIV November 6, 1883, p. 89 ] The Decree was carried on 20 November, 1883. On December 11, 1883, the announcement of appointment of the E.B. Tylor to Readership in Anthropology, tenure from January 1, 1884 was given. According to Stocking [1987: 265] ‘Tylor’s position was structurally anomalous, and his lectures usually drew rather small and heterogeneous audiences, many of them non-academics.’

In that same year [1883] Tylor commenced his first lecture series, held in the Geological Lecture Room at the museum of Natural History. Penniman reported:

Tylor was appointed Reader in 1884, and lectured in the Museum, usually with specimens, demonstrating their working. One of the usual contentions was that to understand a people, one needed a good collection of the objects made by them. In days before the ‘magic lantern’ became general, he used large wall pictures (drawn by Alfred Robinson, the predecessor of Mr Turner), many of which we still have, [18] including his classic series for his lecture on Assyrian winged figures and the fertilisation of the date palm. Perhaps too much is made of the scanty attendance at his lectures, when we recall that people like Henry Balfour, Sir John Myres, Dr. R.R. Marett, Sir Everard Im Thurn, and Sir Baldwin Spencer were among those present. [Penniman, 1953: 13]

Marett remarks that in Tylor’s very first address to the University ‘he declared roundly: “To trace the development of civilization and the laws by which it is governed, nothing is so valuable as the possession of material objects.”’

Tylor’s professional life is discussed by Gosden and Brown [original draft of Brown, 2005,]. According to them Tylor ‘... carried out with other professionals, missionaries, traders and interested parties around the world to gain objects for his research.’ [original draft of Brown, 2005, page 1]

Gosden and Brown comment:

‘The conventional view of Tylor is that material culture was of ‘secondary interest to him’ (Chapman 1987: 37, see also Chapman 1981), especially when compared to someone like Pitt Rivers. Our aims here are to show that artefacts, which were viewed as cultural facts, ... were so basic to Tylor’s view that it is easy to overlook his interest as recourse to material things was a fundamental part of much of his writings. Tylor worked at the Pitt Rivers and University Museums from 1883 for over twenty years, and his publications and private papers suggest his interest in the material world predated his appointment at Oxford (see Freire-Marreco 1994 [1907]). ... [His] collection and the correspondence linked to it, which ... illuminate the sets of connections through which Tylor worked and exchanged objects, photographs and information. This exchange community was vital to Tylor’s social persona, but also to the development of his thought and writing about the world, forming the site for the social production of his knowledge. ... Tylor saw his task as an ethnographer in two stages: first to gather as wide-ranging a set of material as possible on all aspects of human life; second to extract general principles, tendencies and laws from the mass of the particulars in front of him. ... Objects were the most basic of social facts and without the systematic study of artefacts, ethnography would always rest on an insecure basis. Tylor collected, and his collection included fire-drills, rattles, potatoes and hoes, together with myths, stories and accounts of kinship. Because of the primary nature of our sensory appreciation of the world, things were most valuable as the basis for generalisation. Subsequent commentators have focused on Tylor’s generalisations, rather than their empirical basis. Museum collections were to be the bedrock of ethnography, an idea which led Tylor to the Pitt Rivers Museum.’ [original draft of Brown, 2005, pages 1 - 3 of unpublished text]

Tylor also contributed to general anthropological public life; he led the movement that resulted in the creation of an anthropological section of the British Association, and in 1884 acted as its first president. Marett [1936: 14] suggests that the establishment of the anthropological section was ‘largely due to [Tylor’s] efforts’. Also in the same year, according to Chapman:

... arrangements had to be made for packing and shipping and for a place to store materials [from the founding collection] once they did arrive at Oxford. Technically, however, the task was Moseley’s concern, although Tylor apparently made suggestions. During the long vacation of 1884 both undertook a trip to New Mexico, at least partially in search of new specimens, but also to help set the scope and standards of their joint teaching and research venture. [these conclusions are based on Marett’s paper on Tylor] [Chapman, 1981: 487]

Tylor himself describes this visit in his Anniversary Address to the Anthropological Institute:

‘In 1884 we [Moseley and Tylor] went together to the British Association at Montreal, where he presided over the Biological Section, and thence to the American Association at Philadelphia. Then we made a journey into Arizona and New Mexico, under the patronage of the Bureau of Ethnology, and in company of Mr. G.K. Gilbert of the American Geological Survey, with the special object of visiting the Pueblo Indians, and studying in their adobe villages a still-existing matriarchal society, and the continuance of a native religion which has held on through centuries of Spanish dominion. [Tylor, The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 21. (1892), pp. 396-412.]

In 1887 Tylor gave an Account of a Witches Ladder found in Somerset at the BAAS meeting in Manchester. In 1888 he gave an address at the BAAS meeting in Bath. That year he also stayed at Rushmore with the Pitt Rivers [Megan Price, pers. comm.]

In 1888 Edward Tylor wrote to ‘General Pitt Rivers’:

... If I remember rightly, I was beginning to speak to you about the idea of a 3d [i.e. threepenny] Guide to the Pitt Rivers Museum when something else intervened and the subject did not come up again. The idea arose from the old Strangers Guide to the University Museum being now out of print and the Delegates wishing me to make arrangements to get a new one into shape. As this would involve some pages about the Pitt-Rivers [sic] Museum, the possibility suggested itself of these pages being also issued separately for visitors. The space (perhaps 10 - 15 pages 8vo) would be too limited for anything of the nature of a Catalogue but a ground-plan might be given with directions to the stranger where to find some of the principal series. For instance, he might be informed that on entering, he would find in the Court Cases to right and left specimens illustrative of the development of fire-arms from the matchlocks to the wheel-flint, and percussion types. Further to the left, he would come to the wall-case showing the development of the shield from the parrying-stick, and of metal armour from ... [sic illegible] defensive coverings. When he gets this information, the large labels on the cases, so far as Balfour has done them, will tell him more about the meaning of the series. When Balfour returns I will let you know, and I feel sure that your going over the Series with him will promote their being arranged so as to be open to the public (I mean those in the Galleries.) You will be able to ascertain from him what prospect there is of the publication of a Catalogue. To me it seems distant from the amount of work involved and the cost of illustrations. I think your active cooperation would do more than anything else to push it forward. ... P.S. I have just seen Balfour returned from Finland and looking forward to your visit. [Tylor to Pitt Rivers, letter dated October 4 1888, L541 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, Pitt Rivers papers]

The exact role that Tylor played in the Pitt Rivers Museum displays is (and has always been) disputed. Balfour certainly believed that Tylor had little impact in this area (and it is hard to see, other than by lying, how Balfour could not be the ideal witness). However there is some documentary evidence that Balfour might have played down Tylor’s role, at least in the early days. There is for example a letter from Tylor to Boas, dated 9 December 1889 thanking him for some objects and saying ‘I am having the spoons set up in a series’, in other words, presumably, directing Balfour in that task. [This letter is held by the American Philosophical Society and we require permission to use this quote - see file created by Ali Brown in Megan’s pile, it is in pink folder] Marett certainly believed Tylor’s role to be more important than Balfour stated:

‘... it was Tylor himself, aided by Moseley and younger helpers such as Baldwin Spencer, who actually superintended the removal of all this treasure [the Pitt Rivers collection] to its present domicile and reduced it to orderly shape. [Marett, 1936: 15-16]

Balfour seems to have felt that Tylor was given too much recognition for his limited work in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Balfour wrote to Sir Herbert Warren in 1919 that:

‘Tylor never played any part in the internal administration of the Pitt Rivers Museum + was not responsible in any way for its classification, organization or administration. ... it was placed under the care of Prof. Moseley ... until Prof. Moseley retired + I succeeded him as Curator, when he died. … Tylor played no part in the organization + was never asked to do so. It is true that in 1890 an attempt was made by Council to place Tylor over my head, but this fell through, as I very naturally refused to have anything to do with so unfair a scheme, which would have meant his getting the credit for the work I had done + was doing ... Tylor’s appointment was Reader in (+ later Professor of) Anthropology + this did not involve his having supervision of or responsibility in regard to the Pitt Rivers Museum.’ (1st October 1919, PRM? [see Fran Larson's account of Balfour also on this website for details])

According to Chapman, a Committee of Council was formed on 16 May 1890 to look into the possibility of the transfer of responsibility for the Museum from Balfour ‘to the Reader of Anthropology’ (that is, Tylor). [Chapman, 1981: 520] Balfour, in a letter to Professor Price, of the Committee, stated:

I have for some years performed the duties and assumed the responsibilities of executive curator, without having the privileges or title. In view of the fact that Dr Tylor, as he fully admits to me, could not possibly devote to the collection one quarter of the time required for its management, and as he has not studied the system of working the department, I am somewhat surprised that he should be so ready to accept the responsibilities. [Letter dated 15 June 1890, Balfour papers PRM, quoted in Chapman, 1981: 688]

In December 1890 a University decree was passed that Henry Balfour be appointed a Curator of the Pitt-Rivers Museum (as it appears to have been spelt at that time), to hold office for one year and it was reported in the Gazette that ‘during that period he have the same status in regard to the University Museum with the Professors teaching in the Museum.’

According to Megan Price, from around 1890 Alfred Robinson, the (?University) Museum’s ‘demonstrator’ prepared lecture aides (pictures and charts) for Tylor. These are now held in the PRM manuscript collections. She describes them as: ‘Each bears his signature or initial in one corner; some are in colour, others are executed in black ink, often drawn over a pencil sketch prepared by means of a grid (very much the same method as the painters of frescoes in Egyptian tombs). Approx 12 rolls each containing up to 6 charts each.’ By August 2003 Megan and Ellen Cumber (working on a work-experience project) had photographed them, described and annotated a list and placed a copy on the ESRC server [location?] The objects illustrated in the pictures may have come from elsewhere, Megan identified one as being a photograph of the Nimrod ivories (in the Death and Burial) series, as being obtained from the British Museum.

In 1890 Gladstone visited Oxford and visited the Museum ‘for an hour or so’. Tylor had breakfast with him at Balliol College. [Megan Price pers. comm.]

Between 1890 and 1892 Tylor was one of the vice-presidents of the Folklore Society. When Tylor died the Folklore Society journal (vol 28, p. 12) described him as ‘one of its original members’. [Megan Price, pers. comm.] In 1891 Tylor was elected president of the Anthropological Society. In that same year Tylor seems to have attended the International Folklore Congress in October. Other attendees included Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers and Alfred Cort Haddon. According to Megan Price’s notes [pers. comm.] the delegates visited Oxford as the guests of Andrew Lang and John Rhys and ‘[m]embers made acquaintance for the first time with the treasures appertaining to our study preserved at the Pitt Rivers Museum, the significance and importance of which were so convincingly set forth by Dr. Tylor’. [no source given for quote]

Until 1893 Tylor had been giving all the Anthropological lectures at the University. In 1893 his lectures were announced in the Gazette alongside Balfour’s and another series devoted to Physical Anthropology to be given by Arthur Thomson, then lecturer in (soon to become Professor of) Human Anatomy. A special notice announced that, while they were open to anyone who was interested, all these lectures were ‘adapted to meet the requirements of Students taking up Anthropology as a Special Honour Subject’ at the University (13 June 1893, University Gazette XXIII: 603). [Fran Larson, Balfour narrative account]

It seems that Tylor may have become discontented with Oxford life. In 1894 (no more specific date given) his brother Louis wrote to him:

‘... you must be near the Museum and within reach of society yet I suppose Anna could not live in a West End flat. Then you require an income adequate to your taste for gadding about and indeed economy would be bad for your work. Is it not best to set aside thought of change until you have had a long holiday? Your delegates have supported you and you must not let the Beast fish [ramp] over them.’ [Megan Price, pers comm., letter held by Chris Tylor]

The issue may have been one of prestige. A letter written to Anna Tylor at about the same time again from Louis, her brother-in-law, again apparently undated, states:

‘Clearly what you ought to do is to take your time and see if your friends will not only support you but keep up your prestige. If they fail to do this of course you will go sooner or later but do not give your one clear war whoop or what not until the exact moment when it suits you. Of course the Fish [sic] will get some consideration but that need not trouble you. I am glad Edward is going away at once as he is evidently worrying. I rather fancy that a three month sea voyage would the best and many a thing may happen in three months. Do anything except resign if you are beaten. Hold on all the tighter till you see your chance and then - why you won’t care by that time two straws about the whole affair’ [Megan Price, pers. comm., letter held by Chris Tylor]

The row seems to have revolved around the University Museum and not the Pitt Rivers collection (as it probably still was at that time). E. Ray Lankester wished to reform the University Museum and there was controversy at this time ‘concerning Tylor’s use of Museum rooms and of Alfred Robinson’s time’. [Megan Price, pers. comm.] In February 1894 Lankester wrote to the Vice-Chancellor to complain that Tylor (the Keeper of the Museum) had appropriated two rooms and the attendant [sic - previously Megan had described him as a Demonstrator] Alfred Robinson. According to this letter Tylor had ‘detached him [Robinson] from the duties which he was appointed to perform and now calls him the Keeper’s Assistant or ‘Keeper’s Servant’. Really he was engaged as attendant for the Zoological collections …. The Keeper makes little use of the rooms and utilizes the attendant as his secretary and artist ... has appropriated resources and has by statute no duties in the Museum whatever and no rights there. His sole business (according to the Statute) is to inhabit the Museum House and to receive £80 per year.’

Tylor replied on February 26 1894 that Alfred Robinson had entered the Museum in January 1879 where he had been set duties with ‘Henry Smith, Mr Rowell also Prestwich and Moseley. His work has always been general’. By May 5th the problem had been resolved, the first of the two rooms appropriated by Tylor was to be retained by Robinson, the second was to be used as a Delegates Room and by the Keeper and the third was to be given to Lankester as soon as it was vacated by Tylor. [There is an unexplained discrepancy here about the number of rooms involved] [Megan Price, pers. comm.]

In June 1895 a statute was approved to establish a Professorship of Anthropology tenable by E.B. Tylor during his tenureship of the Readership. In 1895 Tylor led a petition to establish a final honour school in Anthropology at Oxford, but Convocation rejected his proposal, something he felt bitter about throughout his life. John Myres remembered that Tylor, ‘resented the rejection of his project for a degree examination in anthropology. It was an unholy alliance he said, between Theology, Literae Humaniores, and Natural Sciences. Theology, teaching the True God, objected to false gods; Literae Humaniores knew only the cultures of Greece and Rome; Natural Sciences were afraid that the new learning would empty their lecture rooms. And the arch-villain was Spooner of New College, whom he never forgave.’ (Anthropology at Oxford 1953 Oxford University Anthropological Society). [Fran Larson, Balfour narrative account]

In 1896 Tylor was unwell and underwent operations on 16 and 30 June [Megan Price, pers. comm.] He seems from this point to suffer an increasing incidence of ill-health, and many of his visits mention famous spas like Baden Baden. In 1905 diaries record that he needed nurses and was in an invalid chair. [Megan Price, pers. comm.] Stocking describes this period thus:

‘In 1896, Tylor suffered a serious illness, and although he published several important articles after that time, it seems to have marked the beginning of a general mental decline, which by 1904 had become quite severe. When Tylor was knighted in 1912, Clodd wondered in his diary if he was even aware of it, since “he has been long mentally dead.”’ [Stocking, 1995: 62]

In 1897 Tylor wrote to ‘General Pitt Rivers’:

I am sorry to hear of your having been out of health of late, but at any rate you manage to keep up your work, which is the greatest of consolations. I speak feelingly having had a long and severe illness last year and though better now, finding work no longer easy. In writing about the kopis series I had better not trust to memory, but in a week or two I shall be back in Oxford and will go over them with Balfour. My impression is that the series is much or altogether on the original lines, and that the drawings go with the specimens. No doubt the geographical continuity in such series is as important as it would be to a zoologist. Indeed the problem which most occupies me is to trace inventions etc from their geographical origins, especially because ideas and customs are so apt to follow the same tracks. In working out the whole course of culture, it seems to me that to follow the diffusion of such a thing as a special weapon, is to lay down the main lines of the whole process, so that I should be among those most interested in the travelling of the Kopis. [Tylor to Pitt Rivers April 13 1897, L1788 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Pitt Rivers papers]

Tylor was reappointed Reader for five years from December 1898. This year was probably the last year in which Pitt Rivers himself expressed his views about the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford:

‘I hardly think that the system [PR’s own system of typological arrangement] has been favourably tried at Oxford. Mr Tylor and Mr Balfour have done their best no doubt, but they do not have the means, the materials, or the funds to work the system thoroughly, and as I soon found out that it was quite impossible that a method communicated by one person should be worked out effectively by others. Some of the series have not been developed at all, and others very imperfectly. the whole collection was out of sight for a long time, five years, I think, whilst the building was being erected, and my health has not allowed me to go there much since. It is not the kind of a building for a developmental collection, which would be better in low long galleries well lighted from above and without pretention; the large and lofty space was not wanted. Rolleston and Moseley were the heads when I gave the collection to Oxford, and Tylor though the best man possible for Sociology, had at that time but little knowledge of the material arts. Balfour, though hard-working, does not, I believe know fully to this day what the original design of the collection was in some cases. I do not however complain of the men. They have done their best to carry out an idea which was an original one at the time, and circumstances have been against it. Oxford was not the place for it, and I should never have sent it there if I had not been ill at the time and anxious to find a resting place for it of some kind in the future. I have always regretted it, and my new museum at Farnham, Dorset, represents my views on the subject much better. I shall write a paper about it before long if I live ...’ [PR letter to FW Rudler 23 May 1898, Salisbury Museum quoted in Chapman, 1981: 535]

In 1898 Tylor was sent a proof copy of Spencer and Gillen's Native tribes of Central Australia, according to Ackerman (Frazer's biographer):

'... Frazer's acting as agent for Spencer and Gillen during the production of their book created, as an unintended by-product, a dispute between him and Tylor. When Macmillan accepted the book for publication, Frazer suggested that Tylor be sent a set of proofs, more as a courtesy than anything else, which was done. Tylor, however, had only recently (in May 1898) proposed to the Anthropological Institute a quite different theory of totemism of his own, one that grew out of his own animistic assumptions, namely (in Frazer's summary) that "the souls of ancestors animate the totem animals or plants, and therefore these animals or plants are sacred to their descendants." Perhaps because Spencer and Gillen's evidence did not support his theory, when the book was already in page proof Tylor proposed to Macmillan that the chapter giving a minute description of the crucial intitchiuma ceremonies be drastically compressed, in order to elide many "tedious and disagreeable details." In a letter to Macmillan ... Frazer disagreed most forcefully ... After a brief exchange Tylor backed down, and the book was published intact.' [Ackerman, 1987: 160]

I have found no other incident to support the charge of intellectual dishonesy implied by Ackerman in this passage. However, I recall from my research into Spencer and Gillen for My Dear Spencer that Tylor's sudden decision to propose changes puzzled and confused the two authors. In July 1898 Gillen reported that Macmillan had provided an 'account of Prof Tylor's opinion is very encouraging...' [Mulvaney et al, 1997: 233] so presumably earlier on Tylor had been positive about the publication but had later realised the implications for his own theory [Mulvaney et al, 1997: 245-6]

A great change to the appearance of the Museum took place in 1901 when the totem pole, acquired by Edward Burnett Tylor, arrived in Oxford. Tylor and his wife had visited a house called Foxwarren Park in Weybridge in 1897 to see the totem pole which had been acquired by Bertram Buxton in 1882, this visit was recorded in Anna Tylor's diary. The owners were distant Fox relatives. This pole was from Masset village. This must have spurred on Tylor’s wish to acquire one for the Museum. [Megan Price, pers comm.] Tylor acquired the pole through the Hudson’s Bay Company via C.F. Newcombe and the Reverend J. Keen.

According to Fran Larson [unpublished]: