ENGLAND: THE OTHER WITHIN

Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Calendar-related artefacts

Christmas

Alison Petch,

Researcher, 'The Other Within'

The Pitt Rivers Museum's English collections do not have many objects specifically related to Christmas. This is perhaps surprising as this season is perhaps the season most widely celebrated throughout England even today. Indeed English, European and North American Christmas traditions have now spread throughout the world, and can be seen as almost divorced from its purpoted religious connections to Christianity. Christmas Day, 25 December in the Anglican and Roman Catholic calendar, was supposed to be the day when Jesus was born in Bethlehem. It has been a public holiday in the United Kingdom for a very long time, in the nineteenth century it was one of only two days on which workers had a statutory right to be absent under the Factory Act of 1833 (the other was Good Friday)[David please link Good Friday to the Good Friday part of the Easter object biography]. [Hutton, 1996:112]

Hutton makes the point that a midwinter festival had probably been celebrated in Britain from 'the dawn of history'. [1996:34] Christmas, in England, occurs at the darkest time of the year, when days are at their shortest. It is also during the cold winter, when food would have been more scarse and life (before the twentieth century) much harder for most people. As Hutton remarks, 'the Christmas season is the most important complex of festivals in the modern British year and contains by far the largest number of customary practices. [1996:112]

Gifts

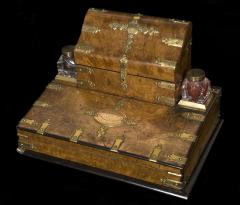

Christmas time is a time for exchanging or giving presents to family and friends. Gifts are sometimes also given to employees, or employers or people to whom the person feels an obligation. The next object, which is Christmas-related, is an oddity, it is described as:'A hideous [sic] fitted desk, 1 ft 2 inches x 10 inches x 9 inches, veneered with bird's eye maple and with brass ornaments, and an inscription on brass: "Presented to Miss S.U. Powys by the members of the Bournemouth Central Workers' Club, Christmas 1877". Tout à fait typique.'[1945.6.124]

It was donated by William Horace Boscawen Somerset in June 1945. It is not known why Bournemouth Central Workers Club felt it should give Miss Powell the desk at Christmas, or why the anonymous accession book recorder in 1945 should feel that the desk was so 'hideous', though there is a rather unattractive underlying note of snobbishness in the final sentence 'tout à fait typique' (loosely translated as 'entirely typical'). This object was not given to the Museum because it was a Christmas gift (indeed the motivation for giving it to the Museum or accepting it seems unclear as it was considered so 'hideous'). The museum has been unable to find out anything more about either Miss Powell or the Bournemouth Central Workers Club and would be grateful for any information on either.

Gift-giving, before the nineteenth century, had traditionally been associated with New Year rather than Christmas Day but during that century, the date gradually changed to Christmas Day, where it has remained. [Hutton, 1996:116] As Hutton points out, dislike of the perceived commercial nature of Christmas started early, 'George Bernard Shaw started an enduring myth in 1897 by declaring that 'Christmas is forced upon a reluctant and disgusted nation by the shopkeepers and the press'.' [1996:116]

We also have other Christmas gifts in the collections, two packets of cigarettes issued by Her Royal Highness the Princess Mary's Christmas Fund, 1914. [1989.44.97-98] When the first world war started, public opinion was firmly on the side of the armed forces, risking their lives for their country. People who remained in England wished to show their support. Thousands of appeals were launched during the First World War but the most memorable was the Princess Mary Christmas Fund. It was launched on 14 October 1914 by Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary (known as Mary), the daughter of King George. She had originally intended to pay (from her personal allowance) for a gift for every soldier and sailor. This was not practical and she was asked to give her name to a public appeal which would provide a gift for every man serving under Admiral St John Jellicoe and Field Marshall Sir John French, around half a million men would benefit. It was decided that the money should be spent on an embossed brass box, based on a design by Messrs Adshead and Ramsey. The cost of each box was 6 1/4 d [pennies] per box. The Appeal proved a great success. The total sum eventually subscribed was £162,591 12s 5d. In the end nearly two million presents were distributed. Because of the distribution problems with such a large number of parcels many people received their gift in the New Year (and were given a New Year card from the King and Queen).

The contents varied considerably; officers and men on active service in the Navy or Army received a box containing a pipe, tinder lighter, one ounce of tobacco, twenty cigarettes in distinctive yellow monogrammed wrappers and a Christmas card. Non-smokers and boys received a brass box, a packet of acid tablets [sic], a khaki writing case containing a pencil, paper and envelopes. [I think most people would consider that a less exciting parcel!] Special provision was made for the foreign troops serving, to take account of their perceived cultural preferences. Nurses received the box, a packet of chocolate and a greetings card. Because some of the contents were difficult to provide at such short notice some other gifts were substituted.

'The 'tin' itself was approximately 5" long by 3¼" wide by 1¼" deep with a double-skinned, hinged, lid. The surface of the lid depicts the head of Princess Mary in the centre, surrounded by a laurel wreath and flanked on either side by the 'M' monogram. At the top, a decorative cartouche contains the words 'Imperium Britannicum' with a sword and scabbard either side. On the lower edge, another cartouche contains the words 'Christmas 1914', which is flanked by the bows of battleships forging through a heavy sea. In the corners, small roundels house the names of the Allies: Belgium, Japan, Montenegro and Servia [sic]; France and Russia are at the edges.' [Information taken from The Princess Mary 1914 Christmas Gift webpage]

The Fund was eventually wound up in 1919 and the remaining funds transferred to the Queen Mary's Maternity Home, founded by the Queen for the benefit of wives and infants of the men who had served.

Candles

A particular emphasis in the winter festivities was always upon light (not surprisingly). In 1725 a Newcastle clergyman commented that many people in the north of England lit huge 'Christmas candles' on Christmas Eve. It seems to have been a matter for each family or local area when the candles were actually lit, some doing so on Christmas Eve, others on Christmas Day; some families had standard-sized candles and others many candles, some of them painted. The aim was to fill the family home with light. [Hutton, 1996:38] The Christmas candles that many people still light today, either to decorate their living-rooms or as a feature of the Christmas meal table in their dining-room reflect this tradition. Today christmas cakes are often decorated with figures of Father Christmas, snowmen and small candles.

Our collections include a box of twelve candles, 1966.3.129 .1-13. These are coloured orange, yellow, grey and green and are arranged in a Christmas box. They were used to decorate a Christmas cake. These candles were bequeathed by Frederick William Robins, who was greatly interested in lighting and had a large collection of such artefacts he bequeathed to the museum. These candles came from Boscombe, Hampshire. The candles are approximately 10 cms high.

Christmas crackers

The final two objects are from Christmas crackers. 2004.3.56 is a blue plastic cup, tiny blue plastic ball and a short length of white string for making a cup and ball game. The gift was probably obtained from a Christmas cracker by the donor, Giles Gaudard Barber. The final object is a fortune-telling fish, also obtained from a cracker, and donated by a conservator then working in the Museumm, Lorraine Rostant. The fish is made from a very thin piece of plastic. It is placed on the hand, and its movement is supposed to indicate various states of mind, which can be interpreted from the instructions accompanying it, e.g if the head moves, the person is 'jealous'. [1998.16.1]Christmas crackers were invented by a London confectioner, Tom Smith. In 1844 he imported the French bon-bon into England, and sales of the new product turned out to be best at Christmas. According to Hutton, 'in 1846,* hearing a log pop on the fire, he hit on the idea of marketing the sweet at that time in a paper wrapping with two handles which detonated a firecracker.' [1996:119] These proved so successful that later the sweet was replaced by a small gift. Tom Smith's company has been the leading manufacturer of crackers in the UK ever since. By the 1870s manufacturers had added paper hats. A cracker is now usually constructed of a small cardboard tube (containing the paper hat, small gift and joke) wrapped in brightly decorated paper which is twisted at either end. The ends are open and the cracker is pulled by two people, breaking a card strip, impregnated with chemicals which runs from end to end, this produces a 'pop'. Crackers are usually bought in boxes of around 10 or 12.

*Both wikipedia and the Tom Smith website [addresses below] give the date as 1847 rather than 1846.

Cards

1965.5.1 237 One of Ettlinger's working catalogue cards showing a Xmas card to her from Peter & Iona Opie

Further reading

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christmas

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christmas_cracker

http://www.tomsmithchristmascrackers.com/how-crackers-were-invented.php

http://collections.iwm.org.uk/server/show/ConWebDoc.994

http://www.kinnethmont.co.uk/1914-1918_files/xmas-box-1914.htm

http://collections.iwm.org.uk/server/show/ConWebDoc.994/

Ronald Hutton. 1996. The Stations of the Sun: A history of the Ritual Year in Britain Oxford: Oxford University Press [especially pages 1-41, 95-123]

Steve Roud. 2006 'The English Year: A month-by-month guide to the nation's customs and festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night' London: Penguin Books [especially pages 366-412]