ENGLAND: THE OTHER WITHIN

Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum

The Pitt Rivers Museum and a Museum for English or British artefacts

Peter Rivière, Fran Larson and Alison Petch

In December 2007 the Telegraph newspaper reported that Gordon Brown, the Prime Minister, had 'put his weight behind [a] campaign for a national museum of history':... while so many other countries have a museum dedicated to their history we in Britain, as Lord Baker says, still do not. Perhaps such a venture would require considerable private backing as well as public funding but I know there are numerous British companies and benefactors who would be interested in offering their support.

And as we take forward our discussions, we will focus not just on how a museum could relate the narrative of British history, but how it could celebrate the great British values on which our culture, politics and society have been shaped.

This is just the latest in a series of attempts to establish a museum for England (or Britain)(depending on the political climate at the time of the proposal).[1]

Pitt Rivers Museum staff were involved in several of these attempts. This page concentrates on these attempts.

Henry Balfour and a British National Museum

In 1904 Henry Balfour was President of the Anthropological Institute, and in this capacity gave the annual address where he discussed 'The Relationship of Museums to the Study of Anthropology'. The last half of his piece is devoted to the need for a National Museum devoted to artefacts from Great Britain:

There is one type of museum in which the British Islands are singularly deficient, and, by some irony of fate, it is one which would fully illustrate the ethnology and culture of the people of Great Britain, that is so conspicuously lacking. We have every reason for being proud of that noble institution the British Museum in Bloomsbury, with its immense wealth of archaeological and ethnological material. At the same time, we must admit that its name applies rather that it is a treasured possession of the British Nation, than that it illustrates it characteristics, developmental history and culture. British archaeology is, it is true, well represented, but there has been little space devoted to a connected treatment of the arts, industries and general culture of the nation through the historical period. This clearly indicates that this phase of the subject must be illustrated elsewhere. We want a National museum, national, that is, in the sense that it deals with the people of the British Islands, their arts, industries, customs and beliefs, local differences in physical and cultural characteristics, the development of appliances, the survival of primitive forms in certain districts, and so forth. Some attention has, I know, been given to these matters, as, for example, in the Antiquaries Museum in Edinburgh, the small private museum at Farnham, Wiltshire, formed by the late General Pitt Rivers, and some other museums and private collections; but nothing of a comprehensive nature has been attempted and we have allowed many interesting, and at one time important customs and appliances, associated with our national life, to die out, without having taken adequate steps to preserve their record. We have no institution in this country which occupies the position of the larger "Folk-museums" of the continent. Paris, Moscow, Stockholm, Christiana and Copenhagen, not to mention other large cities, all have their Folk-museums, illustrating in a most interesting and instructive manner the life of their people, particularly of their peasantry. Nor is it only the great cities, for many of the smaller towns, such as Bergen, Helsingfors, Sarajevo and others, have well-equipped and very popular museums of a similar kind. Surely we have reason to be as interested in our national characteristics as other countries are of theirs, and, surely, the ethnology of and culture developments in Great Britain are as important to us as these subjects are to continental peoples. And yet we still lack an institution in which the non-political history of the British Nation is studied and illustrated in a comprehensive manner. It is not too late even now to start such a National Museum, on the model of the famous Nordiska Museum in Stockholm, the life-work of Dr. A. Hazelius, which combines both indoor and outdoor museums, and which not only illustrates in a splendid manner the life of Scandinavian peoples, but also furnishes a valuable object lesson, as a record of what can be achieved through the enterprise and devotion of one man, starting with but very meagre funds.

There must be a great amount of material, representing the obsolete appliances and customs of Great Britain in the hands of private collectors, which would find its way into such a museum, if it were once started upon a satisfactory and systematic basis; and, with reasonable energy, we might in a few years' time boast of a National Museum which would defy the world to taunt us with the accusation that, while we eagerly look after and make collections illustrative of everybody else's ethnology, we neglect our own. Ethnological museums on an extensive scale are every now and then founded by enlightened private individuals, but, with the establishment of each new one on the old familiar lines, there is the loss of an opportunity for filling a serious gap, and for providing the country with something which it definitely lacks. [p.15-16]

Balfour repeated this call to the Museums Association in 1909. When he remarked on the great many ethnological collections in the Museums of the British Isles, but said,

we cannot fail to become cognizant of one fact, which is that only a comparatively insignificant proportion of the whole has any direct bearing upon the ethnology of Great Britain, and, further, it must be remarked that such British material as is preserved and exhibited usually lacks organization and continuity in its arrangement, and as a necessary consequence, its educational value remains comparatively undeveloped.

Pre- and proto- historic antiquities have already received attention, but little time and effort had been spent on the mediaeval and post-mediaeval period. He again suggested Nordiska Museum in Stockholm as the model for a national folk-museum.

An English Folk Museum

In 1948 the Third Report of the Standing Commission on Museums and Galleries praised the pioneering work of the Welsh Folk Museum. Unfortunately they thought there was no chance of founding an English equivalent from public funds, nor was there an obvious candidate from within existing museums to take on this role. However, the Commission felt that plans should be made for the collection of material which would form the nucleus of such a museum.

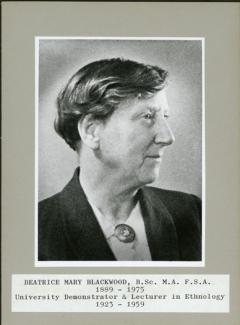

In June 1948 the Royal Anthropological Institute [RAI] set up an Exploratory Committee (to be known as the British Ethnography Committee) to ‘to consider means of promoting the ethnological study of Great Britain in the light of the present state of such studies in this country and abroad’. One of the members of this committee was Beatrice Blackwood, who worked at the Pitt Rivers Museum and was a member of both the RAI and the Folklore Society. The chairman of this committee was Herbert J. Fleure, Professor emeritus of Geography, Manchester University; the Hon. Secretary was William Fagg, then at the Department of Ethnography, British Museum (his brother, Bernard, was later to become Curator of the PRM); Meyer Fortes, Reader in Social Anthropology, Oxford was an ex officio member.

At the first meeting of the Committee it was agreed that the establishment of a museum was the essential step for placing the study of British ethnology on a sound footing. The museum should concentrate on English culture, but include comparative material from elsewhere in Britain and Europe. The name Museum of English Life and Traditions was suggested for the first time. Various potential funding bodies were suggested, though the second meeting of the Committee received news that most of these bodies had attempted to suggest alternatives rather than seizing the opportunity themselves. At the same meeting it was agreed that the Committee should become a standing committee of the Institute in order that representatives from other interested bodies, like the Folklore Society, could belong.

In April 1949 'A scheme for the development of a Museum of English Life and Traditions. A memorandum by the British Ethnography Committee of the Institute, in collaboration with the Folk-Lore Society' was published in Man. This suggested plans to co-ordinate and organize collecting and storing material relating to English cultural traditions, initially through regional museums, in the hope that, 'some large house of architectural and historic interest, within easy access of London, with its surrounding land (a minimum of 200 acres) might be made available or patriotically offered, as a permanent home for the Museum of English Life and Traditions and its open-air section'. [PRM manuscript collections Beatrice Blackwood box 34, ‘Scheme for the development of a museum of English Life and Traditions’]

Copies of the RAI document were widely circulated and discussed and in September of the same year the chairman of the British Ethnography committee (Bagshawe) gave a paper at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science entitled ‘A plea for a museum of English life and traditions’ which garnered a great deal of press interest.

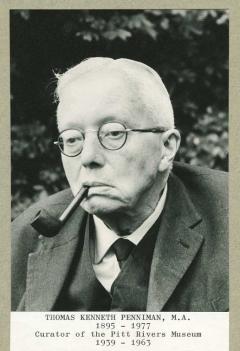

The scheme relied on curators siphoning off material in their collections, or diverting objects presented to them in the future, when they were deemed suitable for the national museum. Penniman wrote that, so far as the Pitt Rivers Museum was concerned, while deaccessioning could be problematic, ‘Should such a Museum be established, it would be our policy when approached by donors or vendors of suitable material, to accept objects which were required for our own series, & put the donor or vendor in touch with the National Museum of Folk-Lore for other material which he might wish to place in a Museum.’ (PRM manuscript collections Beatrice Blackwood box 34, letter from T.K. Penniman, 6 December 1948). Circular letters informing curators of the scheme were also drafted, but, from surviving correspondence between the chair of the Committee [Thomas W. Bagshawe] and Blackwood, it appears that the plans had been shelved by 1950, and Blackwood sent papers relating to the proposed Museum to Bagshawe in Cambridge to be archived.

Although the Committee continued its work for several years, it never achieved its objective of establshing a national museum for British ethnography.

Please Note

A much more detailed account about the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) at Reading and the Museum of English Life and Traditions (MELT), The Tale of Two Museums: Success and Failure will hopefully be published at some future date by Peter Rivière in the Journal of History of Collections.

Further Reading

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1572265/Brown-Why-I-support-British-history-museum.html

Balfour, Henry. 1904. 'President's Address. The Relationship of Museums to the Study of Anthropology' The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 34 (Jan. - Jun., 1904), pp. 10-19 [2]

Balfour, H. 1909. ‘Presidential Address’, The Museums Journal 9 (1909), pp. 5—18.

No name. 1949. '49. A Scheme for the Development of a Museum of English Life and Traditions.' Man, Vol. 49 (Apr., 1949), pp. 41-43

Notes

[1] The most recent at the time of writing this web page (February 2009) was an initiative by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council [MLA, a quango of central Government in the UK). Called a museum of Britishness, it announced on 3 February 2009 the establishment of a Museum Centre for British History:

The MLA has consulted a range of leading experts, and has recommended the idea of a federated organisation that could draw on the collections in museums, libraries, archives and heritage sites across the UK to capture the story of Britain. The proposed centre would co-ordinate research and scholarship, plan thematic programmes, and schedule shows and events in places across the country.

See this website for further information. My thanks to Ollie Douglas for pointing this press release out to Alison Petch.

[2] N.B. Jstor mistakenly attributes this address to W. Gowland, but a quick check in the previous item clarifies that Balfour was definitely the President of the Anthropological Institute that year, and thus the address is his.