Native American performance

© Pitt Rivers MuseumHistorical drawing of Tewa Pueblo Indians, Arizona or New Mexico, USA, c. 1912

© Pitt Rivers MuseumHistorical drawing of Tewa Pueblo Indians, Arizona or New Mexico, USA, c. 1912

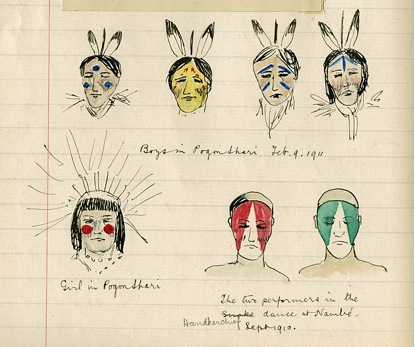

Barbara Freire-Marreco made this field drawing in her notebook on a study trip to Arizona and New Mexico. It now forms part of the Pitt Rivers Museum's accession books.

Freire-Marreco had been the only female member of the first class of anthropology students to graduate from Oxford in 1908 and in the course of her life donated several hundred objects to the Museum relating to Native American cultures. During this particular trip in 1911–12 she studied the various Tewa Pueblo communities, each of which have their own distinctive languages and identity. The sketches illustrate the face paintings and feather headdresses as worn in the performance of sacred dances a century ago. At the time, the collector also obtained some specimens or red pigment and wrote:

"Pueblo Indians redden their faces on all festive and full dress occasions, such as dances; when setting out on a journey or to undertake some important piece of work; to express cheerfulness, energy, recovery from an illness; and on winter mornings to keep out the cold."

However, the precise significance of the patterns and colours used in bodily decoration is something known to the Tewa alone. Despite pressures to conform to neighbouring American or Hispanic modes of material culture, economy and social organisation, the Tewa ritual calendar of village performance has remained a strong and fiercely protected thread in Tewa cultural continuity.

This is not to say that the Tewa have not adapted. Over time they have carefully and selectively blended elements of Western symbols or theatrical conventions into their own forms of ritual performance – whether in terms of formation, movement, costume or music – to create a fresh and relevant interpretation of an ancient tradition. Thus two modes of dance can be said to co-exist: the theatrical shows performed outside the village for tourists, and the sacred dances within the community itself.

For the Tewa, secrecy is the key to maintaining the power and vitality of the performances. The theatrical shows are imbued with as much sincerity and meaning as the private ones and are performed to promote rainfall, harvest, and to bring blessings and good health upon the community. The tourists who witness these events are discouraged from photography, filming or asking invasive questions. This value on discretion extends within the Tewa community itself; for example in the preparations and execution of ritual dances, members of the older generations may be privy to religious information that the younger ones are not.