Prehistory of the Pitt Rivers Museum

This document was written during the ESRC funded Relational Museum project between 2002 and 2006 by Alison Petch and Frances Larson (the researchers on the project). The project looked at the networkers of collectors and museum staff who had formed the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum up to 1945 and the history of the Museum up to 1945. This document reflects those interests.

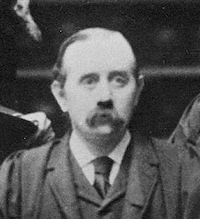

H.N. Moseley, the first Curator responsible for the Pitt Rivers Collection at OxfordThis document has not been extensively revised since it was completed at the end of 2006, and may not reflect the fullest knowledge available to the Scoping Museum Anthropology full project team at the time of writing. AP has quickly reviewed its contents though to make it as consistent as possible with other pages as they were in April 2013, when this article was added to the SMA website.

H.N. Moseley, the first Curator responsible for the Pitt Rivers Collection at OxfordThis document has not been extensively revised since it was completed at the end of 2006, and may not reflect the fullest knowledge available to the Scoping Museum Anthropology full project team at the time of writing. AP has quickly reviewed its contents though to make it as consistent as possible with other pages as they were in April 2013, when this article was added to the SMA website.

See here for some of the correspondence which relates to this time period, about the founding collection and early history of the Pitt Rivers Museum:

The history of the Pitt Rivers Museum and its collections stretches back before 1884, the date usually given for its foundation. Not only did its foundation depend upon the donation of the collection amassed before 1884 by Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, but the transfer of items deemed to be ‘ethnographic in content’ from the Ashmolean Museum [AM] and later the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (as it is now known [OUMNH]). These collections were acquired before 1886 and (mostly) obviously predate the foundation date. The history of the museum and its collections therefore needs to be seen as part of the complicated web, not only of Pitt Rivers’ total collection but also of the University of Oxford’s ethnographic collections, which date back to the Tradescants’ collections given to the University by Elias Ashmole in the seventeenth century.

The first dates of significance related to the Pitt Rivers Museum’s collections therefore is 1683 when the Ashmolean Museum opened at its original site on Broad Street.[1] The recent gift of the collection presented to the University of Oxford by Elias Ashmole (1617-92) was already half a century old by this time, having been founded by John Tradescant (died 1638) and displayed to the public (for a fee), first by him and later by his son John (1608-62) in their house in London. The contents were universal in scope, with man-made and natural specimens from every corner of the known world. By the time it passed to Ashmole by deed of gift, the Tradescants' collection of miscellaneous curiosities had grown in scale and stature to the point where its new owner could present it to the University as a major scientific resource. So the Museum opened in Broad Street under its first curator, Dr Robert Plot, as an integrated, three-part institution, comprising the collection itself, a chemistry laboratory for experimentation and teaching, and rooms for undergraduate lectures. [based upon the account given on the Ashmolean Museum’s website: http://www.ashmol.ox.ac.uk/ash/faqs/q003/]. Part of the Tradescants’ collection together with other ethnographic objects accumulated by the Ashmolean museum between 1683 and 1886 were transferred to the newly opened Pitt Rivers Museum in 1886. Some of these ethnographic objects are of great historical importance, particularly perhaps the items collected by George and Johann Reinhold Forster during the Cook voyage of 1772-1775.

The next significant dates occurred in the 1840s when the University first began to take an interest in developing its museums and collections (hitherto formally and solely concentrated at the Ashmolean) by agreeing in principle to the development of a separate natural history museum and University Gallery. However, some of the colleges had scientific collections, such as Christ Church [see on]. According to Howell:

[The University Museum] owed its existence to a heroic band of champions of science, and above all to Dr Henry Acland, who in 1849 engineered a resolution to the effect that, in view of the entirely inadequate provision for the teaching of Natural Science, and the chaotic condition of the University’s scientific collections, a museum should be built to assemble “all the materials explanatory of the structure of the earth, and of the organic beings placed upon it’, together with teaching accommodation. [Howell, 2000:739]

The natural history collections had been scattered around the University and the Colleges, and included such important accumulations as the natural history part of the great Ashmolean Museum collections, a large comparative anatomy and physiology collection held at Christ Church (for the history of the ethnographic section of this college's collections, see on], and the Dean Buckland's collection of fossils. As David Berry explains:

‘On 1 May ... [of 1849], a meeting of 21 members of Convocation was held in the lodgings of David Williams, Warden of New College, to discuss the idea of establishing a new museum. At this meeting, it was resolved ‘that in order to enable the University to carry into effect the vote of Convocation which established a School of Natural Science it is desirable that a general University Museum be formed with distinct departments under one roof, together with lecture rooms and all such appliances as may be found necessary for teaching and studying the natural history of the earth and its inhabitants’. [Vernon-Harcourt 1910,5]’ [Berry, 2003:225]

During 1853 four acres of land were purchased for the new museum of natural history (on what is now called Parks Road in central Oxford) from Merton College. [Fox, 1997: 650] The Keeper for the new museum, John Phillips, was appointed. The drive to create a single building to house and display all the material and to be the centre of the teaching of natural sciences [2] in Oxford came from Sir Henry Acland, the then Regius Professor of Medicine. As David Berry explains ‘[t]o assist architects in the preparation of designs [for the University Museum in 1854], a Statement of the Requirements of the Oxford University Museum was issued by the third delegacy (with the help of the architect, Rohde Hawkins). This statement included the following information:

‘To increase the value of the Collections illustrative of Natural History, and to aid the School of Natural Science in the University, it is desirable that a General University Museum be formed with distinct departments under one roof, together with Lecture Rooms and apartments for the use of Professors and working-rooms for Students. It has been determined that this Museum shall be a Building of two stories in height, in the form of three sides of a quadrangle, and the area covered in by a glass roof; the fourth side being so adapted as to admit of extension of the building at some future period.’ [Berry, 2003:227-8]

The design of the University Museum was also set out in the Statement, it was to be of two storeys, ‘in it were to be specialized museums or apparatus rooms for medicine, physiology and anatomy, zoology, geology, mineralogy, chemistry and experimental philosophy. In addition there were to be seven lecture-rooms (including one capable of seating 500), a library, a detached residence for the Curator (later redesignated as Keeper), accommodation for a porter and two servants, and generous provision for laboratories and dissecting rooms, private work-rooms, store-rooms, workshops and individual sitting-rooms for the professors and readers, [3] including the Savilian Professors of Astronomy and Geometry and the Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy. Most importantly, easy communication was to be ensured by the arrangement of the facilities around the three sides of a common central courtyard roofed in glass, leaving the fourth side for future extension.’ [Fox, 1997:651]

In June 1860 the British Association for the Advancement of Science held its annual eight day meeting at Oxford. During the meeting a special meeting was held in the still unfinished library of the new museum, featuring the debate on evolution theory between Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Henry Huxley. [4]

The new Museum building was structurally completed in 1860, and is now considered a gem of middle Victorian neo-Gothic architecture (for further information about the Museum of Natural History’s history see http://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/history.htm). Moves were now made to occupy the building under the ‘meticulous supervision of Phillips in his capacity as Keeper of the Museum (a position he held from 1858 until his death in 1874...’ [Fox, 1997:657] The work of installation was completed in ‘the early months of 1861’. [Fox, 1997: 657] A plan of the University Museum circa 1866 shown in Fox, 1997: 662 shows that the eastern side of the Museum was still marked ‘side for extension’. The museum was thought to need potential room for extension from its inception. This was, of course, the side upon which the Pitt Rivers Museum was later built. The newly occupied building was described by F.G. Stephens in Macmillan’s Magazine as ‘there is hardly any modern public building which even nearly approaches its beauty or dignity.’ [Fox, 1997:660] The new building ‘gave disciplines immediate access to a common central court roofed in glass. The court, which was bounded by open arcades on the ground-floor and first-floor levels, was devoted to collections, in particular those of geology and mineralogy, palaeontology, zoology and anatomy and physiology, and to cabinets housing the apparatus for experimental philosophy... it was essential to the plan that communication between the departments should be easy.’ [Fox, 1997:660] ‘There was only one science which had no place in the scheme, to Acland’s enduring regret. This was botany, the base for which remained in the Botanic Garden.’ [Fox, 1997:661]

From the first, the University Museum suffered from lack of space,

‘in 1863 Westwood commented on the shortage of space for the zoological specimens: ‘you may fancy how wretched the arrangements for zoological purposes are when I tell you that Cases covering about 6 square yards are allotted for the general Collection of Mammalia! But the most humiliating illustration is that of the Strickland collection of birds which [was] .. formally offered to the University in 1860. By 1866 ... Phillips had to advise the Vice-Chancellor ... that no space for the collection could be found ...’ [Fox, 1997:673]

Despite this perceived lack of space it was not long after this that there were moves to transfer other University collections from one institution to another. Macgregor footnotes an early attempt ‘in a letter addressed to the Vice-Chancellor on 26 Jan. 1867 by George Rolleston, the University Professor of Anatomy and Physiology, and himself a archaeologist, in which he advocates the relocating of the archaeological and anthropological collections to a new gallery to be built adjoining the University Museum [AA AmS 45]’. [Macgregor, 1997: 603 footnote 26] In the 1860s there were moves to transfer the scientific collections from Christ Church College to the University Museum. In fact Dr Lee's trustees loaned their collections to the OUMNH and to this day [2005] these collections remain the formal property of the College and not the Pitt Rivers Museum (and other museums). [Jeremy Coote pers comm] The most famous part of the Christ Church collection was the collection of 'Cook first voyage' material. Coote has demonstrated [2005] how this collection was probably first given by Joseph Banks to the college before January 1773 [Coote, 2004:7] Part of the collection was later transferred to the OUMNH in 1860, upon that museum's foundation. [Coote, 2004:7] The second half of the collection was transferred direct from Christ Church to the Pitt Rivers Museum in 1886, possibly via the OUMNH or Ashmolean Museum. [Coote, 2004:7-8]

Part of this transfer of scientific collections from different parts of the University did not take place until 1886, after the Pitt Rivers Museum had been established and the founding collection received; the totality, of course, never occurred as British archaeological collections remained at the Ashmolean Museum itself.

In the 1870s attention shifts to the founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum. Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers had been amassing his collection from the 1850s. His intellectual interest in collecting archaeological and ethnographic objects came out of his early professional interests in the development of firearms which he outlined in a lecture delivered in 1858.[5] As Tylor describes it, ‘In order to follow ... [the evolution of design in firearms] he collected series of weapons ... the method of development series extending itself as appropriate generally to implements, appliances and products of human life, such as boats, looms, dress, musical instruments, magical and religious symbols, artistic decoration and writing, the collection reached the dimension of a museum.’ [Tylor, DNB entry:1141] He kept his collection in his house at first where Tylor describes how ‘he collected weapons until they lined the walls of his London house from cellar to attic’. [Chapman, 1987:31]

Pitt Rivers was a strong believer in the role of museums in public education:

The knowledge of the facts of evolution, and of the processes of gradual development, is the one great knowledge that we have to inculcate, whether in natural history or in the arts and institutions of mankind; and this knowledge can be taught by museums, provided they are arranged in such a manner that those who run may read. [Pitt Rivers, 1891:116, quoted in Chapman, 1991:137.] [6]

In 1872 he loaned a number of musical instruments for a special exhibition at South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum). From 1874 parts of his collection (numbering about 10,000 objects in total) were displayed at the Bethnal Green branch of the South Kensington Museum. The whole of Pitt Rivers’ collections were never publicly displayed together, the items which were displayed at Bethnal Green (and later transferred to the main South Kensington Museum) formed the collection donated to the University of Oxford, parts of his collections were kept privately in his houses but another large portion of his collections were displayed at his private museum at Farnham, Dorset.

The displays in London followed his interests in the development of particular designs and in evolution:

The objects are arranged in sequence with a view to show ... the successive ideas by which the minds of men in a primitive condition of culture have progressed in the development of their arts from the simple to the complex, and from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous. ... Human ideas as represented by the various products of human industry, are capable of classification into genera, species and varieties in the same manner as the products of the vegetable and animal kingdoms ... If, therefore, we can obtain a sufficient number of objects to represent the succession of ideas, it will be found that they are capable of being arranged in museums upon a similar plan. [Pitt Rivers, 1874:xi and xii]

and would have resembled, in appearance, those of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (at least up to 1945):

... Table cabinets were placed at the centre of the room, standing cabinets and simple pegboards around the periphery, along with drawings. The whole was carefully arranged ... The first segment of the exhibit, was devoted to skull types and other physical features including samples of skin and hair. Drawings ... supplemented actual specimens ... The second part of the collection was ‘Weapons’, beginning with the display of throwing sticks and parrying shields ...[Chapman, 1981:374]

In 1878 his collection was moved to the main South Kensington Museum where it was allocated ‘two rooms in the Exhibition Galleries on the western side of the Horticultural Gardens’.[Pitt Rivers, 1874:frontispiece.] As Chapman has explained:

Pitt Rivers’ occasional arguments with those in charge of his collections at South Kensington served to underline a far more fundamental concern: whether he was planning to make his collection a truly public foundation by relinquishing his ties with it, or whether he was to keep it for himself. It was a decision that Pitt Rivers had been avoiding for a number of years. Still, something had to be done soon, and it was clear that the South Kensington authorities would no longer tolerate his attempts to retain control over the details of arrangement or add to or subtract from his collection as he pleased. The outcome was, as the Council on Education informed Pitt Rivers in late 1879, that the Museum would have to be given complete control if the collection was to remain on display there. ... In the early part of 1880, Pitt Rivers became suddenly and unexpectedly the heir to a great fortune ... For the first time Pitt Rivers had the means to purchase in an unrestricted way ... he let Richard Thompson at South Kensington know that he would ‘extend much more rapidly than hitherto the Ethnographical collection now exhibited at South Kensington.’ He was also anxious, as he explained, to provide for a more permanent kind of foundation ... I shall want nearly double the space at once, and if my intentions are fulfilled, more rooms will be required immediately’. [Chapman, 1984:13]

In 1880 he offered his collection to the South Kensington Museum. In April 1880, General Pitt Rivers wrote to the Assistant Director of the South Kensington Museum, explaining that he intended to expand his collection rapidly and would require more room.

'I propose, if I live [Pitt Rivers was ill with diabetes], to extend much more rapidly than hitherto the Ethnological Collection now exhibited at the South Kensington to which as you know I have devoted much attention during the last twenty five years and I am anxious to know whether in view of such extension the Museum Authorities will undertake the housing and exhibition of it or whether it will be necessary for me to seek accommodation for it elsewhere.

The collection now occupies the rooms L and H ... on the ground floor and it is intimated that there are 14,000 objects in it, but the space is insufficient to exhibit even the present collection properly and the arrangement on which the value of the series mainly depends cannot be fully carried out with the present accommodation I shall want nearly double the space at once and if my intentions are fulfilled more room with be required ultimately.

It may be usefull [sic] that I should state briefly the plan on which the objects have been brought together in order that it may be understood why a collection of this kind should exist side by side with other Ethnological or Colonial exhibitions. My collection differs from others in this that the arrangement is psychological rather than geographical, that is to say, objects from different countries appertaining to .... or phases of the human mind have been classed together, the intention being to shew how far one nation has borrowed from another on the other hand to what extent the phases of art have arisen spontaneously in different Countries and to trace the development of each branch. I do not affirm that all Museums should be arranged upon this plan but having been in constant communication with men of science on the subject, anthropologists and others, I find that the utility of this arrangement is recognized as a means of shewing connections which could not be brought to light otherwise. ... If the Museum Authorities decide to give me the space I require with any prospect of permanence there is one point to which I would invite attention viz that the arrangements for superintendence which are satisfactory in the case of other collections which having been once handed over to the Museum remain constantly in the same cases, without change or addition are not satisfactory in the case of my collection to which additions are being made daily, and which must be subject to constant arrangement as the things accumulate. The objects are collected with a view of demonstrating certain principles of evolution and it is quite necessary that the superintendent should understand what those principles are and enter into the spirit of the arrangement. Either it will be necessary to have an officer in the position of a Curator who has special qualifications for the post or the person superintending must be a subordinate officer of intelligence whose time is devoted exclusively to the Collection and who will act under my guidance, I shall be most happy to provide and pay the Superintendent myself, if that arrangement meets the views of the authorities, but I think I need not dilate upon a point so obvious further than to say that to carry out the extension of my Museum in the manner proposed with the system of superintendence which has been in vogue hitherto would be impracticable.

If it should be decided not to entertain the proposal which I now make with respect to the collection generally, I hope that sufficient time may be given me either to make other arrangements or to build a Museum of my own.

I may add that my intention is if I am able to increase the Museum in such a way as to make it worthy of the purpose for which it has been commenced to leave it to the nation or to some other Nation or to some Institution which will carry it on.” [Letter from PR to Thompson 14.4.1880 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum [henceforth SSWM], P125]

It may be that Pitt Rivers had already offered his collection to the nation by this stage, and that the committee created to consider his offer had already been set up: see SSWM, P134, which is a letter drafting the terms of Pitt Rivers’ offer to the nation and which appears to be dated 1879 [see SSWM catalogue]. This letter stipulates that Pitt Rivers must retain management of the collection, and that he would provide and pay for a curator should his offer be accepted. Pitt Rivers’ conditions were designed to ‘insure its being properly maintained in its present arrangement, and prevent the possibility of its being broken up and distributed amongst other collections by any future authorities who might not thoroughly comprehend its importance in its present condition’ according to an article in Nature [23 September 1880:490]

Only a matter of weeks after Pitt Rivers’ letter to the Assistant Director of South Kensington, George Rolleston (then Linacre Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Oxford) was invited to join a committee detailed to ‘report on the Collection and on the advantage to Science and Art which may be expected to accrue from the proposal made by Pitt-Rivers [to donate his collection to the nation]’. Rolleston was invited to join the committee in May 1880 [SSWM, P127]. The existing members were John Lubbock, Fergusson, [?Thomas Henry] Huxley, Poynter, Cunliffe-Owen and Colonel Donelly. Augustus Wollaston Franks was also on the committee, but joined sometime during or after July [PRM foundation volume, PR to Franks, 1 July 1880]. The committee reported favourably sometime between May, when Rolleston joined, and September 1880. Although its conclusions had not been officially announced yet, Nature reported that the committee had ‘reported unanimously in favour of its being accepted’ in September [1880:490].

Despite this, the government ultimately rejected the General’s offer. Following the committee’s report, negotiations seem to have broken down over whether the collection should be subsumed into the South Kensington Museum or the British Museum, and over the specific terms Pitt Rivers had laid down regarding the ongoing care and maintenance of the collection. It would appear, from a letter written by Pitt Rivers to the Daily News, that the government decided that the proper place for an ethnological collection was within the ethnological department of the British Museum, not at the South Kensington Museum. Pitt Rivers replied that his collection was in no sense ethnological, but was a museum of primitive arts designed to show their development [SSWM, P137]. This was a weak argument, given that he had described it as an ethnological collection when originally making the offer to the nation (ibid). Neither does it make sense in light of his earlier letter to Franks [1 July 1880, PRM foundation volume] when he voiced a preference for the British Museum over South Kensington, which was too focussed on ‘aesthetics’ and not ‘scientific’ enough. In this letter Pitt Rivers also voiced some apprehension when it came to his specific conditions. He worried that the British Museum would not, ‘adapt itself to the peculiar conditions and accept the Museum subject to my having the control of it during my life.’ He went on,

‘I consider this a sine que non. It would not be possible to carry out my views in any other way. My object is, more space with a view to increase the collection, and as the accumulations will be made with a view to the special arrangement the management in so far as the arrangement of the objects is concerned must be in my hands… I am most anxious that my collection should be carried on in harmony with the British Museum and I consider that the utility of my museum would depend in a great measure upon its being in harmony. I have no doubt that I should secure a good deal of valuable assistance from the officers of the Museum if my collection were attached to them and that it might very likely become desirable to modify my system in some measure to meet their views, but it would be essential that freedom of action should be retained.’ [PRM foundation volume]

Pitt Rivers was suspicious of government bureaucracy and was keen to retain complete control over the collection despite his offer to hand it over to the nation. He seems to have been rather critical of the British Museum from the start: ‘As a means of education for the public the B.M. is useless. I shall supply that want.’ [PR to Franks, June ?1881, PRM foundation volume] South Kensington had refused him more space, and the British Museum were not willing to meet his demands for space or ongoing control (ibid). Franks no longer supported the proposition, and Pitt Rivers began to think about other possibilities for his collection:

‘I shall build a museum in or close to London about the size of the room I have at present. Keep the bulk of the collection in trays or drawers and exhibit only a few things in cases, but I shall not have space enough to continue the series and I must make the museum valuable in other ways I shall become a collector of ethnological gems and [unclear] I die. I have received no encouragement to leave anything to the nation. If the nation will not accept my offer now on account of a dog in the manger rivalry between the two departments I shall take good care it never gets anything from me.’ [PR to Franks, June ?1881, PRM foundation volume]

In June 1881 the offer was rejected by the Council, by the autumn of that year the museum authorities refused to accept any more materials from him on loan. The ongoing negotiations with Oxford do not seem to have affected Pitt Rivers’ day-to-day collecting habits, because in December 1881 attempts were made to stop him from adding to the collection at South Kensington, since his tenure of the galleries might terminate at any time and all the objects would have to be removed rapidly

“The hands of the Committee of Council on Education learn that some additions have been sent in by you to your Anthropological Collection in the Western Galleries since the termination of the Correspondence between you and their Lordships as to the transfer of the Collection. You are aware that the tenure of their Lordships of these galleries is very uncertain, and that they are liable to be called on to give them up and to remove all their contents at short notice. They have no desire to press for the removal of your Collection until the decision as to their tenure of the Galleries make it necessary; but they do not feel it desirable under existing circumstances that any further additions should be made to it, and they will not be able to provide cases or other fittings for the reception of any such additions. They would suggest that the attention of the Curator (who they learn from your letter of August 31 has been appointed by you) should be directed to the necessary preparation for facilitating the ready removal of the collection which may have to be carried out in great haste.” [SSWM, Letter from G.F. Duncombe to PR 14.12.1881, P131].

Indeed, the pamphlet issued by Oxford in January 1883, designed to help members of the University to make an informed decision about accepting the collection, reiterated the fact that the collection was estimated to contain 14,000 objects two years previously [PRM foundation volume]. He therefore cast about for suitable alternatives, eventually settled upon the University of Oxford.

It may be that the suggestion of Oxford University as a home for the collection had already been broached by this time (this depends on the exact date of the Franks letter quoted above, which is unclear), because in March 1881 Henry Nottidge Moseley wrote to Franks about the Oxford possibility. He stated that, on the suggestion of Professor Westwood (John Obadiah Westwood was an entomologist and palaeographer, and the University’s first Hope Professor of Zoology), Pitt Rivers had offered his collection to the University of Oxford. Pitt Rivers had authorized Moseley to make the offer on his behalf, ‘on the condition that the University finds a building etc.’, and the proposal was due to come before the Hebdomadal Council in April 1881. The idea was apparently broached with plans for more formalized teaching of anthropology already in mind, because Moseley added,

‘I think the collection would be a splendid gain to Oxford and would do much in the way of letting light into the place and would draw well. Besides of course it would act as introduction to all the other art collections and about to be made and would be of extreme value to students of anthropology in which subject we hope to allow men to take degrees very shortly.’

(Note: we do not know when moves started to bring Edward Burnett Tylor to Oxford as Keeper of the University Museum – he gave his first lectures at Oxford in February 1883, shortly before becoming Keeper, but discussions about bringing him to Oxford probably started much earlier). In 1883 the University Gazettes record the appointment of Tylor to the first anthropological academic post in the UK. A Decree submitted in November 1883 proposing appointment of a Reader in Anthropology, with stipend of £200 a year. Shall lecture in each of three University terms, for not less than six weeks, once in each week. Students for informal instruction twice each week he lectures. Any student receiving informal instruction shall give no more than £2 a term, otherwise all lectures open and free to members of University. [Vol. XIV November 6, 1883, p. 89 ] The Decree was carried, 20 November, 1883, [p. 128] On December 11, 1883, the announcement of appointment of the E.B. Tylor to Readership in Anthropology, tenure from January 1, 1884 was given [p. 192])

Moseley appealed for letters of support for the Pitt Rivers donation from Franks, Tylor and John Evans. Moseley continued the Oxford-Pitt Rivers campaign following the death of George Rolleston, who had been on the original Committee to consider Pitt Rivers’ offer to the nation in 1880. Rolleston and Pitt Rivers were good friends. They were both archaeologists and worked on excavations together and had toured Sweden together in 1879 [Paton 2004, DNB entry for Rolleston]. Rolleston died suddenly of kidney failure in June 1881, and Moseley replaced him as Linacre Professor of Anatomy (Rolleston’s Chair was split following his death). Although it is hard to be sure what kind of a role Rolleston took in the earliest negotiations between Pitt Rivers and Oxford, Pitt Rivers later wrote to Acland,

‘[I] wish you every success in your endeavours to promote anthropology in Oxford. Professor Rolleston often talked to me about it and we can’t but wish that he had lived to carry it out.’ [21 May 1882, Bod, MS. Acland d.92, fols.75-76]

A committee of members of Convocation was appointed to consider Pitt Rivers’ offer, and they produced a report for the Hebdomadal Council in January 1882. The Committee consisted of the Regius Professor of Medicine (Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland), Professor Smith (probably Henry Smith, mathematician and Keeper of the OUM?), Professor Prestwich (John Prestwich, Professor of Geology), Professor Westwood, Professor Moseley and Mr Pelham (Henry Francis Pelham, historian (of Rome), tutor in classics at Exeter College). These men apparently visited the collection during the course of their deliberations:

‘The Committee have examined the Collection on several occasions, and having had its contents and purposes explained to them by Major-General Pitt-Rivers in person, are thoroughly convinced of its great importance, and, believing that its presence in Oxford could not but prove of great assistance to students in almost all branches of study, and of great value in aiding general education…’ [PRM foundation volume]

Interestingly, Pitt Rivers wanted this Committee to draw up the terms of the agreement, so his position at this stage with regard to ongoing control contrasted with that expressed during negotiations with the British Museum [ibid]. [NB the suggested terms are detailed in this Committee Report, and an ‘Approximate Estimate of the Museum-Space required’ and associated costs, supplied by Gilbert R. Redgrave ‘Assoc. Inst. C.E.’ is appended. Redgrave was recommended by the Department of Science and Art at South Kensington.] However, Pitt Rivers did voice disquiet in a letter to Acland, dated May 1882, over the suggestion that his objects should be added to those already held by the Ashmolean:

‘I am afraid the incorporation of the Ashmolean Museum with mine may spoil it. Valuable as the objects in that Museum are it has a different object & had better be kept apart.’ [21 May 1882, Bod, MS. Acland d.92, fols.75-76]

For a short but detailed description of the founding collection prior to its transfer to Oxford we have to rely on the account given in 1883 to the Hebdomadal Council by the ‘Committee of Members of Convocation appointed to consider the offer by Major-General Pitt-Rivers ... of his Anthropological Collection to the University and advice them’ dated January 19 1883:

The following rough summary of the contents of the Collection may serve to illustrate what has been said:—

(1) A collection of prehistoric weapons and instruments, including a specially valuable series of Palaeolithic weapons from Acton. A fine series of Neolithic weapons from Denmark. A series of stone and bronze weapons from Ireland. A series of stone hammers. A series showing the gradual conversion of the simple bronze celt into the socketed form. Lastly, series of bronze hammers, of spear-heads and swords, and of implements of bone and ivory.

(ii) A collection of objects belonging to historic times.

A. Collection of weapons (of this a printed catalogue already exists) including—

(a) Defensive Armour :— Series of parrying sticks and shields from Australia, India and Polynesia. European shields of fifteenth century. Series of circular shields. Body armour from Polynesia, Japan, and China; Mogul scale and chain armour. Series of helmets, including bronze Greek and Etruscan helmets.

(b) Offensive weapons :— Series of boomerangs from Australia, India and North Africa. Throwing sticks. Bows. Cross-bows and quivers. Series of clubs, maces, and wooden battle-axes. Series of paddles, spears, javelins, and arrows. Series illustrating the development of the axe, halberd, glaive, and other cognate weapons. Several series illustrating the development and geographical distribution of various forms of swords, daggers, slings, lassoes, &c. A series of fire arms. A series showing the growth of the bayonet.

B. Collection of objects connected with domestic life, &c.

(a) Series illustrating modes of kindling fire :— Savage fire-sticks, flints, tinder-boxes, &c. Series of lamps (Babylonian, Roman, Egyptian, modern Algerian). Collections of mirrors, spoons, knives, &c.

(b) Valuable series of pottery and of bronze, silver, and glass vessels, illustrating especially the development of the various forms, and of the decorative patterns. This series comprises, besides a remarkably fine stand of Cypriote [sic] vases, Greco-Etruscan pottery, Samian ware, specimens from Mexico, Peru, India, Africa, Algeria, Japan &c; and also a collection of decorated gourds, and of basket-work.

(c) A collection of personal ornaments, necklaces, armlets, clasps, fibulae, &c, illustrating the development of particular forms. Especially valuable are the various series of gold and bronze ornaments (Cypriote [sic], Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Celtic, and Mexican).

(d) A collection showing the development of musical instruments (drums, stringed instruments, shell, horn, ivory, and bronze trumpets, &c.).

(e) A collection of objects of religious worship, and of charms, votive offerings, relics, divining-rods, &c. The series of votive offerings is very interesting. It ranges over a wide field, from ancient Cyprus to modern Brittany, and exhibits the most instructive coincidences of belief and ritual.

(f) A series illustrating the growth of the art of writing, including savage marks, Oghams, Runic inscriptions, &c.

(g) Series illustrating the realistic representation of human and animal forms (including some very fine terra cottas from Cyprus and Tanagra, Roman and Etruscan bronzes, Japanese masks of the sixteenth century, &c.). Series illustrating the conventionalised treatment of animal forms in decoration.

Series of mediæval panels illustrating the development of leaf-patterns out of architectural designs (to this the history of mural paintings at Pompeii offers an exact parallel, in the gradual transformation of the architectural designs into ornamental borders).

(h) A collection of harness, horse-shoes, spurs, and stirrups, ancient and modern.

(i) A series illustrating the history of boat and ship-building, comprising many beautifully-executed models of savage canoes.

... Oxford, January 1883.’

It seems likely that this proposal-–which may have been entirely informal and personal-–was rejected because of the space required to house Pitt Rivers’ collection. The terms of agreement proposed by the Committee of Convocation [January 1882] began with the statement that ‘in the event of the acceptance of the Collection the University shall build a separate annex to the present University Museum to receive the Collection.’ Pitt Rivers’ comments regarding the Ashmolean suggest that he was not aware of this proposal yet, or that the terms were still under negotiation.

The group leading the charge in Oxford – Moseley, Acland, Westwood, and others—clearly saw the donation as a chance to further the cause of Anthropology at the University. As already noted, Moseley hoped to attract students to the subject, and Pitt Rivers had offered Acland luck in his ‘endeavours to promote anthropology in Oxford’. In May 1882, Pitt Rivers responded, in great depth, to a set of ‘proposed schedules of study for Honours in Anthropology’ sent to him by Hatchett Jackson. His letter, which outlines the different ‘sub-sections’ of anthropology and their relationships to each other, is kept in the Acland papers at the Bodleian [MS Acland d. 92, fols. 79-90]. So, it seems that efforts to establish a Final Honour School in Anthropology at Oxford began well before Tylor’s campaign in the early 1890s. Tylor–-or at least his position at Oxford-–may well have been part of an earlier, on-going campaign, rather than leader of the first campaign.

The Delegates of the University Museum considered Pitt Rivers’ offer at a meeting in April 1882, at the request of the Hebdomadal Council. They also appointed a Committee, comprising Acland, Moseley, Westwood and Prestwich, ‘to report on the amount of space which the Collection would occupy, and on the probable cost which would be required for new building and cases’ [OUMNH, minutes of the meetings of Delegates, 1867-1888, 1882.7]. In November 1882, the Keeper of the University Museum was able to report that a deputation had been appointed by the Hebdomadal Council ‘to confer with General Pitt Rivers on the subject of his proposal to give to the University his ethnological collection’. The deputation consisted of Friedrich Max Müller, Professor Archibald Henry Sayce (friend of Müller’s and deputy Professor of Comparative Philology), Canon Stubbs (possibly Canon William Stubbs, the historian and later (1888) Bishop of Oxford?), Acland, Westwood, Prestwich, Moseley, Maskelyn? (Mervyn Herbert Nevil Story-Maskelyne or Mervyn Herbert Nevil Story Maskelyne, Professor of Mineralogy Oxford), Mr Pelham and the Keeper (Henry Smith) [OUMNH, minutes of the meetings of Delegates, 1867-1888, 1882.12].

A decree, to be brought before University Convocation, stating that Pitt Rivers’ offer should be accepted, was published in the Gazette in May 1882, along with the letters of support from Franks, Tylor and John Evans [one reason to put full names at least in the first instance is to remove confusion, in this case marked confusion as it could be Arthur John Evans] that Moseley had petitioned them for, over a year earlier. The University accepted the offer on 30 May 1882, but negotiations regarding the terms of the gift continued.

The responsibility for specimens was a more open matter, however, ... much of the actual process of arrangement, cataloguing, sorting and even cleaning was left to various assistants, usually termed ‘demonstrators’ or simply to enthusiastic undergraduates. ... The impression is that everyone, including Moseley himself, assumed that the particulars would simply work themselves out. Moreoever it was apparently understood that the actual process of arrangement and transfer would be a one-time operation, and that subsequent care would follow more or less routine procedures. The assumption could not have been more wrong. [Chapman, 1981:473]

There had been ethnographic displays in the OUMNH prior to the Pitt Rivers Collection. There are references to the Cook collections being displayed there and the following excerpt from the Gazette makes it clear that any interesting ethnographic collections that came in may have been given a display, it is not clear whether these displays were meant to be permanent or merely temporary 'new accession' displays:

'Donation to the University Museum. The Delegates of the Museum announce that four Peruvian Mummies, from Angon near Lima, presented by Commander W. Acland, R.N., have been opened and examined; and that a series of objects of ethnological interest obtained from them are now on view in the University Museum. These objects comprise children's toys, grotesque ornaments, articles of food, and specimens of coloured fabrics, with patterns and figures of animals, characteristic of Peruvian art.' [Note in the 'Oxford University Gazette' vol. XIII no.436, 28 November 1882]

Indeed it seems that ethnographic displays continued there after 1884, as a letter from Moseley to William Gamlen sent on 1.11.1886 shows:

‘I include amongst such specimens those which with the sanction of the University have been transferred from the Ashmolean to the Pitt Rivers collection in exchange for objects formerly in the General Museum, a certain number of objects transferred directly from the General Museum to the Pitt Rivers collection, and a very few objects presented by various donors to the Pitt Rivers collection since it arrived at Oxford. The whole of these additions to the collection as presented by General Pitt Rivers to the University form a very small proportion of the whole. That portion of the objects received from the Ashmolean Museum which is known as ‘Captain Cook’s collection’ has been arranged in a case formerly used for ethnological objects in the General Museum not in a new one purchased for the purpose.’ [Oxford University Archives, University Chest files, UC/FF/60/2/3]

In a report to the Hebdomadal Council of the ‘Committee of Members of Convocation appointed to consider the offer by Major-General Pitt-Rivers ... of his Anthropological Collection to the University and advice them’ dated January 19 1883, the members stated:

The Committee having examined the Collection on several occasions, and having had its content and purposes explained to them by Major-General Pitt-Rivers in person, are thoroughly convinced of its great importance, and believing that its presence in Oxford could not but prove of great assistance to students in almost all branches of study, and of great value in aiding general education, strongly urge the Hebdomadal Council to take such steps as shall enable the University to become possessed of it. Major-General Pitt-Rivers having expressed a wish that the Committee should themselves draw up the terms on which the Collection should be received from him by the University, the Committee have suggested the following, which have been ascertained to be satisfactory to him:

1. That in the event of the acceptance of the Collection the University shall build a separate annex to the present University Museum to receive the Collection.

2. That the annex shall be used solely for the Collection, and for additions to be made to it from time to time, and that an inscription designating the Collection as ‘The Pitt-Rivers Collection’[7] [sic] be affixed over the entrance to the annex, and that the title be permanently retained as that of the Collection.

3. That the general mode of arrangement at present adopted in the Collection be maintained; that no change be made in details during the lifetime of General Pitt-Rivers without his consent; and that any change in details to be made subsequently shall be such only as are necessitated by the advance of knowledge, and as do not affect the general principle originated by the donor.

4. That the University undertake from time to time to expand and complete by the addition of further specimens such of the series of objects in the Collection as are at present more or less imperfect. Such specimens will bear on their labels the names of their donor or of collections from which they may have been derived. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/1]

In this document is also enclosed a report by Gilbert R. Redgrave, described as ‘an expert recommended by the Department of Science and Art at South Kensington’, which provided an estimate of dimensions of a building ‘suitable to a reception of the Collection’. He stated:

The Anthropological Collection of General Pitt-Rivers is at present arranged in three side-lighted rooms at South Kensington ... The total [area of these rooms is] 9390 square feet. ... [after calculations] I think that not less than 7000 sq. ft. should be obtained. The width stipulated for being 70 ft. it would require a building 100 feet in length to produce the necessary area, though it would be possible to arrange for the display of the Collection in a building only 86 ft long. ... I am of opinion that the extra area of wall-space which is obtained in a gallery 100 ft in length will not be undesirable, and, looking to the probable use of the Museum by the public, the additional floor space will be of great advantage. In order to utilize the walls for the exhibition of objects on screens, it will be necessary to introduce narrow galleries of sufficient width for two persons to pass. In a gallery of this kind only a limited extent of wall above the head of the visitor can be seen to advantage ... say about 8 ft in height. ... I believe that the level of the first gallery should be fixed at about 16 ft from the floor, while the upper gallery might be, as proposed, 12 ft above the first. At these levels the line of shadow cast by the gallery will fall clear of the screens. ... My estimate of the entire cost of a building of the form I have shown, together with the glass cases, is therefore £10,120.

There were also two plans included with the Hebdomadal Council report showing the Museum.

In May 1883, arrangements were being made at South Kensington for an inventory to be made prior to the removal of the collection to Oxford [SSWM, P132]. Unless this is Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum P116, which seems unlikely, this inventory has never been found (unless it is the books known as the 'delivery catalogues'?). In a letter dated 6 July 1883 Morrell and Son, soliticitors wrote to William Gamlen (Secretary of the University, see People in left hand menu for further details) saying that the matter of executing the Deed of Gift was 'standing over' whilst a catalogue of the collection was being completed and printed. They had heard from Farrer and Co. (presumably Pitt Rivers' solicitors) that the following conditions had been added:

‘1) That a Lecturer shall be appointed by the University who shall yearly give Lectures at Oxford on Anthropology

‘2) That the Donor and his agents shall have the right at all reasonable times of making drawings of the objects in the collection for purposes of publication’

Morrell had replied that a decision was only possible during October term, but that he could not imagine any objection to (2) but (1) would involve an annual outlay and he do not know what view the University would take. ‘To this Messrs Farrer reply that they understood that it had been already agreed by the University Authorities but that they quite consent that it should stand over.’ [University archives UC/FF/60/2/1] On 27 July 1883 Morrel and Son confirmed to Gamlen that Pitt Rivers had declined to execute the deed until the University had inserted his conditions into the deed. [University archives UC/FF/60/2/1]

In June 1883 Deane wrote to William Gamlen saying that plans were now available for the surveyor, the possibility of adding a (lecture) theatre was mentioned (but no details given). [University archives UC/FF/60/2/1] On 24 July 1883 Howard MacGarvey (Hydraulic and Sanitary Engineer, plumber, iron and brass founder) wrote to Deane, referring to plans for heating the 'new anthropological museum and laboratories' and enclosing a plan [University archives, UC/FF/60/1]

In 1883 the University Gazettes record the appointment of Tylor to the first Anthropological academic post in the UK. A Decree submitted in November 1883 proposing appointment of a Reader in Anthropology, with stipend of £200 a year. Shall lecture in each of three University terms, for not less than six weeks, once in each week. Students for informal instruction twice each week he lectures. Any student receiving informal instruction shall give no more than £2 a term, otherwise all lectures open and free to members of University. [Vol. XIV November 6, 1883, p. 89] The Decree was carried, 20 November, 1883, [p. 128] On December 11, 1883, the announcement of appointment of the E.B. Tylor to Readership in Anthropology, tenure from January 1, 1884 was given [p. 192] In 1883, Tylor commenced his first lecture series, held in the Geological Lecture Room at the museum of Natural History.

According to Chapman during 1883-4:

... arrangements had to be made for packing and shipping and for a place to store materials once they did arrive at Oxford. Technically, however, the task was Moseley’s concern, although Tylor apparently made suggestions. During the long vacation of 1884 both undertook a trip to New Mexico, at least partially in search of new specimens, but also to help set the scope and standards of their joint teaching and research venture. [these conclusions are based on Marett’s paper on Tylor] [Chapman, 1981:487]

The need to save money on the Museum building had meant that reduced plans were not completed until November 1884 and even at that time the design was far from settled.

By reducing the building’s length by a third and introducing a number of changes in the design of the roof and galleries, [T.N. Deane] had managed to reduce the cost to £8,230 or almost within the limits prescribed by the Hebdomadal Council. [Chapman, 1981: 487]

Deane had suggested that the building could be much improved if a small amount of additional funding was allowed but this was refused. In addition it is clear that building an annexe to the existing Oxford University Museum of Natural History led to debate, within that museum, about the best use of the space:

‘A second illustration of want of sufficient attention to the future is to be found in the Pitt Rivers Museum. The Pitt Rivers Collection was given on condition of an adequate and suitable museum being erected. When the time came for acting on this, Dr. Rolleston being had been removed from us. The details came by agreement under his successor Mr Moseley who became Professor of Anatomy, Dr Rolleston’s subject being divided between two Professors of Anatomy and Physiology. Mr Moseley had therefore the chief part in making the arrangements – I was on the committee with him. We would not agree in the matter of breaking the level of the two courts. For cheapness sake only we were to descend several steps, injurious in several ways. Had the level been kept a large basement would have been made, with extension space for storeroom with basements on the north and south sides suitable for laboratories [or workrooms – added to later draft]. It has been often regretted that in the great court this had not been done. But then then Architects felt it to be impossible for certain reasons in that court to do this. The cost of the few feet of wall on three sides of the Pitt Rivers was not worth discussing in so large an issue for the future.' [1885/1 History of OUMNH 1874-1902 Box 2, HW Acland correspondence]

There may well have been further debate for which evidence does not survive.

On May 13 1884 the University Gazette recorded the publication of the Deed of Gift and Declaration of Trust of the Pitt Rivers Collection in lieu of the Deed sanctioned by Convocation on June 5 1883. In a letter dated 2 December 1884 Morrell and Son (soliticitors) sent Gamlen the Deed of Gift dated 20 May 1884. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

Henry Nottidge Moseley (1844-1891), Linacre Professor of human and comparative anatomy at Oxford, was put in charge of the collection and Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917) was appointed the first Reader in Anthropology in Britain.[8] Tylor had been ‘invited to deliver two lectures on anthropology in the University Museum in February 1883, which attracted large audiences’. [Chapman, 2000: 501] Tylor had already been appointed as Keeper of the Museum of Natural History in 1883, succeeding Henry Smith.[9] As he was the Keeper he lived in Museum House, ‘a large and ornate Victorian Gothic building in the Museum grounds, dating from about 1860, soon after the completion of the University Museum, which it matched in style. It was later used to provide additional accommodation for various scientific departments, including storage space for the Pitt Rivers Museum, until it was demolished in 1954 to make way for a new Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory’. [Blackwood, 1970:10]

In 1884, Tylor commenced his first lecture series, held in the Geological Lecture Room at the museum of Natural History. Penniman reported:

Tylor was appointed Reader in 1884, and lectured in the Museum, usually with specimens, demonstrating their working. One of the usual contentions was that to understand a people, one needed a good collection of the objects made by them. In days before the ‘magic lantern’ became general, he used large wall pictures (drawn by Alfred Robinson, the predecessor of Mr Turner), many of which we still have, [10] including his classic series for his lecture on Assyrian winged figures and the fertilisation of the date palm. Perhaps too much is made of the scanty attendance at his lectures, when we recall that people like Henry Balfour, Sir John Myres, Dr. R.R. Marett, Sir Everard Im Thurn, and Sir Baldwin Spencer were among those present. [Penniman, 1953:13]

The University undertook to carry on Pitt Rivers’ general method of arrangement of objects during his lifetime and agreed that any changes after that date would only be instituted if ‘the advance of knowledge required it’. [Chapman, 1981:478] Although Pitt Rivers’ original stipulations had suggested an on-going interest in his collection once it was given to Oxford, in fact he did not display much interest in it after this date, transferring his interest to his new museum in Farnham, Dorset. However, he did remain in contact with Oxford at least until 1891 when the Museum formally opened (see on).

According to Chapman:

By the end of the summer of 1885, materials had begun to arrive at Oxford. The precise order of delivery or exactly how the boxes were initially accommodated are unclear, since no records of the transfers were made either by Moseley or Tylor. No records exist either of the overall nature of the collection at the time other than the two-volume delivery catalogue compiled by the South Kensington staff and given to Moseley presumably at the time of transfer. The latter also provides no indication of the South Kensington books, or how the collection was moved to Oxford or what items might have gone first. Something of the sequence, however, can be reconstructed by referring to correspondence of the period. Upon arrival at Oxford the collection was placed in storage, in several rooms at the University Museum and in a number of other University buildings, including the Ashmolean. There it stayed until individual pieces could be properly sorted by Moseley and Spencer. Actual unpacking, however, was not possible until the annex was complete and during the whole of 1885, the building was still under construction with its scaffolding in place. In the meantime, a preliminary survey could be carried out, and although no record remains of staffs’ thoughts on that procedure, it is clear that at least the order of arrangement was established at that time. [Chapman, 1981:489-490]

On 10 June 1884 the form of tender was signed by Symm and Co, the builders, confirming that they were prepared to erect the Museum in accordance with the plans and specifications of T.N. Deane and Sons and giving costs of £4,977 (with a range of possible additional costs also given). [University archives UC/FF/60/2/1] A further contract was signed with Symm and Co on 24 March 1885. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 4 July 1884 Moseley wrote to William Gamlen that he had seen Augustus Wollaston Franks 'in town' (presumably London) that day and Franks had said he would not value the Pitt Rivers collection but advised insuring it for £10,000 (about the same cost as the building etc), 'this I expect is the best I can do'. [University archives UC/FF/60/2/1 http://eh.net/hmit/ppowerbp/ calculates that £10,000 in 1884 would have been worth £637,113.69p in 2002].

On 12 November 1884 a report of the Committee on the Pitt-Rivers [sic] Museum for the Hebdomadal Council referred to the reduction of original tenders, primarily by changing the structure of the roof and galleries and by diminishing the length of the building by 14 feet (equivalent to a reduction of one-seventh). The report noted that the ‘whole area will not be proportionately reduced, because the galleries are increased in width from five feet to ten feet’ and recommended an application for a further grant so as not to reduce length of building [University archives, UC/FF/60/1] [Frances Larson has noted in her notes that according to these plans originally there were going to be two doors on both sides of the PRM court connecting to the OUMNH, rather than one central door).

On November 25 1884 a decree was noted ‘That the Curators of the University Chest be authorised to expend an additional sum not exceeding £1600 on the Pitt Rivers Building, and on fittings and expenses of removal.’ Note was also taken of the decree passed March 7, 1883. ‘Of the total £7500 it was estimated that £3000 would be required for the cases and for the expenses of removal and arrangement, thus leaving £4500 available for the building itself, a sum which there was reason to believe would prove sufficient. Mr. Deane, the architect already engaged in the erection of the Physiological Laboratory, was instructed to prepare plans and procure estimates for a building of the required size, to be laid before the Curators of the Chest. The estimated cost of the building, as returned by him, was £7092 13s 4d., and a Committee of Council was appointed to examine this estimate with a view to its reduction. The result of their labours was to reduce the estimate from £7092 13s. 4d. to £5445 12s. To this must be added a sum of £400 for the Architect and Clerk of Works. With the £3000, this makes £8845 12s. exceeding the original quote of £7500 by £1345 12s. Proposed £1600 allows for contingencies. A further decree was noted allowing for £200 to be spent on enlarging the boiler house, being built in connection with the Pitt Rivers annexe, for future warming of the University Museum as well as the PRM.’

A letter dated 27 January 1885 from the Secretary of the Science and Art Department, South Kensington Museum to E.B. Tylor stated that the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education had agreed regarding the two requests that that Museum provided 'men and vans necessary for the packing and removal of the Pitt-Rivers Collection' if the University Delegates paid the costs, and the request that SKM Department would present the wooden wall screens upon which weapons etc are arranged at present to Oxford. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2] On 11 February 1885 Tylor wrote to William Gamlen giving details of the requirements for cases drawn up by Tylor and Moseley with cost estimates:

28 ft of court cases 700 896

340 ft wall cases 600 680

250 ft desk cases 306 450

extra for drawers, cupboards 150

internal fittings, linings, locks 200

contingencies 124

total 2,500

[University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 19 March 1885 Tylor wrote again to Gamlen forwarding the case estimate from F. Sage and Co, of £25 per court case including delivery and set up in the University Museum (£8 or more less than Holland and Sons, presumably a rival quotation). Tylor reported that he had seen their work at the College of Surgeons Museum and had been over their factory and had approved it all. He would try and arrange a joint examination with Moseley. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2] On 15 May 1885 F. Sage wrote to Gamlen confirming that cases would begin to be delivered on 1 June 1885. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On the same day [11.2.1885] Moseley also wrote to Gamlen:

‘On going to the Pitt Rivers Collection yesterday I found that it had been shifted out of its place by the S. Kensington authorities and packed closely into one room. The galleries formerly occupied by it were ordered to be cleared for the patent collection. I think the cases have been moved carefully and that the objects are not injured but it is impossible to get at any but those adjoining the passage.

‘I believe that General Pitt Rivers will receive the first intimation of what has been done from a letter I have written to him tonight. I imagine the Curators of the Chest to whom I beg you will communicate the content of this letter will have to ascertain in how short a time the building for the collection will be ready for its reception and then ask the S. Kensington authorities whether they will permit the collection to remain as now stored till that time. It would also be well to have the collection examined to find out whether it will deteriorate as now placed I could not speak with any confidence on the matter after the very short view I had of it. If the Kensington authorities refuse to house the collection till the building is ready the things will have to be moved to some temporary resting place here. In that case the finer cases which will be required for the new building had better be ordered at once. As all the best things in the collection are now in cases which belong to S. Kensington and would not be stored here safely and so as to preserve their arrangement except in similar cases.’[University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 21 February 1885 the Secretary of the Science and Art Department, South Kensington Museum wrote to William Gamlen:

‘…although the Department is anxious to disturb the Pitt Rivers Collection as little as possible, it is quite out of its power to undertake that it shall remain in its present situation until the proposed new building at Oxford is ready for its reception. The Collection is at present placed in a Gallery which does not belong to the Department, and which it has received notice to vacate as soon as possible, as the building is required by the Treasury and the Office of Works for other purposes.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

The Secretary hoped that the Pitt Rivers collection would be removed as soon as possible. On 25 March the Secretary wrote again to Gamlen asking that steps be taken to remove the Pitt Rivers Collection before the end of next May (presumably May 1885?). [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 18 May 1885 Moseley wrote to Gamlen that:

‘I think you had better arrange with the S. Kensington people in the first instance about the removal but you must refer them to Tylor and me for instructions as to the order in which things are to be moved and the superintendence of the job. Some have to come here others to go to the Clarendon building and the packing must be arranged accordingly. You will I suppose let the builders know that the opening into this building will have to be ready by June 1st for the cases and also an ascent of some kind to the hole outside.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 23 May 1885 he again wrote:

‘The Authorities of the Science and Art Department have presented to the University a series of wall screens made especially for the Pitt Rivers Collection and to which a considerable portion of the collection still remains attached.

‘It will be most convenient that the screens should be brought here and stored till they can be erected in the new building, with the exhibits attached to them. As they are of large size it will be impossible to get them in to the rooms at present available without cutting them into short lengths a matter of expense and not without risk of damage to the specimens. It will therefore be of great advantage if some University building the approaches of which will allow the entrance of the screens intact can be devoted to their storage for six or eight months from the beginning of next month. And I beg that you will bring the matter before the Curators of the University Chest.

‘The extreme size of the screens is 9ft by 12ft. Most of them are 9ft by 9ft 3.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

On 30 May 1885 Duncombe (the Secretary Science and Art Department, South Kensington Museum) wrote to William Gamlen that the SKM would be ready to pack the Pitt Rivers collection at a day's notice of the date when Moseley and Tylor could be present. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

One of the people who helped to move the collection from London to Oxford later became one of the most famous Australian anthropologists, Walter Baldwin Spencer (1860-1929)[WBS]. He later wrote to (Henry) Balfour, who also helped in the move, of this time:

.... it was the old Pitt Rivers collection that first gave me my real interest in Anthropology. It was, I think, in 1884 or 5 that Moseley asked me if I would spend the vacation in helping to pack up the collection which was then housed at South Kensington. I did a great deal of the packing up and it was intensely interesting to have Moseley and Tylor coming in and hear them talking about things. [PRM Archives, Spencer papers, Box IV: letter 21, 24 September 1920]

Penniman remarked that, ‘Two of his [Moseley’s] research pupils were Henry Balfour and his life-long friend Baldwin Spencer, both of whom volunteered to go to South Kensington to help to pack the Museum, and to unpack it on arrival at Oxford.’ [Penniman, 1953:12] According to Balfour in an unposted letter to Pitt Rivers dated 2 December 1890 actual arrangement of the displays did not begin until ‘some time after the year (1886) had turned’. [quoted in Chapman, 1981:682]

On 12 June 1885 Moseley wrote to Gamlen that ‘It is very possible we may want to begin to store some Pitt Rivers things in the Clarendon upper rooms tomorrow. Will you kindly tell the Curators and see if they can be swept out etc.' and ‘I am off to town with Tylor to superintend.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2] On 17 June 1885 Tylor was 'in town about the Pitt-Rivers collection' staying at the Athenaeum [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2] A letter from Moseley to Poulton in June 1885 in which he states, ‘I have to go to town on the Pitt Rivers packing business…’ [OUMNH, E.B. Poulton mss.]) confirms this timetable. On 22 June 1885 Moseley wrote to Gamlen that he had just heard that the staircase down into the court had been reduced in width from six feet to 4 ft 2 inches:

‘I cannot conceive how a serviceable building is ever turned out of the University on a system of this kind. We have devised the building and are responsible for its efficience [sic] for the purpose of taking the collection for which it is intended and yet a most important alteration is permitted without a hint to us who are the people who will suffer by the error.

‘The six foot doorway half blocked by a wall of brick only three feet distant from it in a direct line will look absurd and hideous. The four feet two stairway will not allow the carrying down of a single one of the 28 cases now erected in the old building…The front door of the Old Museum was so ludicrously bungled through oversight that it is inconvenient and useless and now we are day by day with our eyes open making a worse bungle of the entrance of the new building.’

Sage says the cases will have to be taken to pieces again to get them down the stairs now. The door is six foot and the stairs 4 ft 2, therefore part of the door is blocked by an internal wall coming to meet the corner of the stairs.

‘How will Pitt Rivers like to see his inscription over such an abortion? Tylor is going to the Vice-Chancellor about the matter. …'

‘I do trust that if it is proposed to abolish the galleries or omit the skylights or build up hermetically all approaches to the building we shall be afforded an opportunity of expressing our disapprobation first.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

Baldwin Spencer [WBS] had become Moseley's assistant from Easter 1885, replacing S.J. Hickson. His main duties included supervision of laboratory classes and a course of lectures. In March 1885 he was involved in reorganizing the zoological collections. [Mulvaney, 1985:54, 55] In June 1885 Spencer was recruited by Moseley to help with the move of the Pitt Rivers Collection from London. 'Spencer estimated that there were some 15,000 items, "and as each of them required labelling a considerable work has to be done. The Government people are removing it ... but we can't trust them to do the labelling ... We three began in the mornings and go on till 5.30 with only a short break for lunch. However, it is rather interesting, if tiring work: Tylor himself is of course the best anthropologist in England and a very nice man indeed."' [Mulvaney, 1985:60][no clear source of quote given in endnote, probably WBS to H Goulty 21 27 June 7 July 1885 PRM ms collections see here]

'The move occupied Moseley, Tylor and Spencer for over four weeks. It is generally believed that Henry Balfour assisted them, but Spencer's letters are explicit that only 3 persons were involved. Once the collection reached Oxford, however, it had to be inspected and placed in the new museum. Although Spencer did not refer to these further duties, he must have assisted with them. A decade later, during his wordy disagreement with Lankester, Tylor wrote that Spencer and Balfour were given the Keeper's room in the University Museum while they handled the collection - and they 'used the room for a long time'. [Mulvaney, 1985: 60, same end note refs as last quote plus Radcliffe Science Lib 2B9:11 (Tylor) See also Spencer's recollections as expressed to Balfour in Marett and Penniman p. 163]

On 3 July 1885 Moseley wrote to Gamlen enclosing a statement of expenses for himself and Walter Baldwin Spencer, 'I have paid Spencer the £6.9.8' [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2] He also enquires about railings for the galleries, and requires a drawing so that he can decide whether to fit the desk cases to the railings. He wrote again on 25 July 1885 devising a system for which cases should be made for the Museum. On the basis of this plan ‘the Keeper and I recommended the order of the 28 transparent cases to fill the available floor space with proper intervals’. For wall cases: ‘In selecting the kind of wall cases to be recommended I first got an estimate at per foot run by subsequently thinking it better to get an offer to make the entire set of wall cases required for a lump sum including a certain modification of breadth for 23 feet in the middle of the east wall…’ etc.

The original plans were suggested by Redgrave and adopted by the University Chest Curators. Moseley guaranteed the plans as correct in his letter to Messrs Sage (the case-makers). Sage offered 240 ft of wall case for £600. It seemed they now needed 6 ft extra of wall cases, which will cost £2.10 per foot (ie £13 10s in all), but peculiarities of requirement (e.g. for going round door to PRM etc) meant that it would probably be more than this. He requested an up to date plan so that he could confirm design of cases, case doors and partitions. He also needed 12 additional feet of desk cases. It was confirmed that the breadth of building was now 76 ft not 70 ft. The situation needed to confirmed before Sage began work. ‘I have given a very great deal of my time to the Pitt Rivers matter’ and had been trying to save expense. [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

Objects were still being removed from South Kensington in January and February 1886, but these were sent to Pitt Rivers’ home address in London, rather than to Oxford [SSWM, P133].

At this time the Pitt Rivers collection was considered a department or annexe of the larger museum rather than a separate entity. It is not clear when the museum did become separate, no University decree to that effect has been found to date and there was certainly no such decree up to the end of 1945. In his 1991 re-publication (and updating) of Blackwood’s Origin and Development of the PRM Schuyler Jones states:

‘From the early days of the Museum, when we were a Department of the University Museum (Natural History) next door ... In early Annual Reports the Museum was referred to as the ‘Ethnological Department’ and later as the ‘Ethnology Department’, being formally designated as the Department of Ethnology and Prehistory in 1958. [1991:17]

Up to 1939, Balfour wrote direct to the University Chest (and Secretary / Registrar) about building maintenance and costs within the department. After 1939 Penniman also wrote to the University Chest directly about financial details, showing that the Museum’s accounts were separate from the Museum of Natural History. The Museum began to post annual reports of its own from the late 1970s, arguably 1974-1975. It is clear that the Museum did not post separate annual reports up to 1945 (so in that respect at least it must have been considered still to be an adjunct of the Museum of Natural History) throughout this period. In 1957 Council promoted legislation to change the title of the Department of Ethnology to the Department of Ethnology and Prehistory, and stated that the Pitt Rivers Collection formed part of the said Department and the building in which the main part of the collection was housed would be named the Pitt Rivers Museum. Fagg was both Curator and Head of Department of Ethnology and Prehistory. During the 1960s a separate Board of Delegates or Visitors for the PRM was established and separate annual reports from this group were agreed in 1966, although the academic side of the museum was still associated with the Faculty of Anthropology and Geography (itself established in 1938). In March 1964 the Delegates for the University Museum (which had also covered the Pitt Rivers Museum, up to that date) changed their name to the Delegates for the Science Area.

When Arthur Evans became Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in 1884 he quickly proposed ‘the transfer to the new (Pitt Rivers) anthropological museum almost the entire ethnological holdings of the Ashmolean. Some of these, he pointed out, of the utmost importance, including, for example, the items brought from the Pacific by Forster, and the material collected by the Tradescants and forming part of the Ashmolean’s seventeenth-century foundation collection. In return various holdings in the University Museum, the Taylorian building, and the Bodleian Library were earmarked by Evans as appropriate for transfer to the Ashmolean. Amongst these was the entire coin cabinet, housed inappropriately and inaccessibly in the Bodleian ...’ [Macgregor, 1997:607]

On 12 October 1885 Moseley wrote to Gamlen that it was necessary for him to have the help of a skilled assistant for a year to aid him arranging and labelling the Pitt Rivers Collection:

'I think I shall be able to obtain such aid as I require for a payment of £100. I propose merely to make the engagement for the job without any suggestion of future employment and I shall be much obliged if you will apply for me to the curators of the University Chest for permission to [unclear – enfeud?] £100 of the sum allotted to the purposes of the collection in the payment of such an assistant.’ [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/2]

He would also require a carpenter for some six months or a year to fit and fix wall screens, shelves brackets etc and so useful jobs.