Snaphance revolving pistol

(1884.27.87 and 1969.4.1)

It is commonly thought that Samuel Colt invented the revolver in the mid-1800s. Whilst Colt certainly made the weapon popular and practical, the concept of multiple shots delivered by a revolving cylinder goes back much further in time.

Here are two versions of the same gun, one authentic, the other a 20th-century copy. The original (top) was made by the London gunmaker J. Annely in the early 1700s, during the reign of Queen Anne. Measuring 12 inches in length, it has a brass barrel of 72 bore attached to an eight-shot rotating cylinder. The brass ball-butt, common for the period, is engraved with a Tudor-style rose. Along the side of the cylinder can be seen eight separate depressions with small holes. These are the priming pans for the eight chambers inside. Sadly, the mechanism, trigger and pan covers are all missing. Fortunately, it was discovered that the Royal Armouries hold a very similar, if not identical, gun with its parts intact so we can see exactly how it worked.

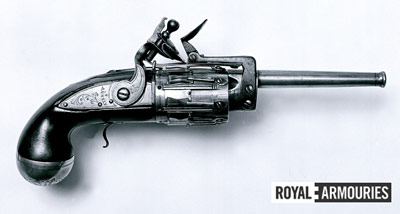

Annely snaphance, c. 1710 at the Royal Armouries. Copyright The Board of Trustees of the Armouries. XII.4745

Here we see how the original snaphance mechanism worked. The snaphance was developed in Germany in the mid-1500s and was the precursor to the flintlock. The name derived from the Dutch schnapp hahn, meaning ‘pecking hen’, referring to the lever and beak-like jaws which held the flint (and which led to the name ‘cock’ for that part of the mechanism). Pulling the trigger released the cock, striking the flint down onto a steel pan, showering sparks on the powder in the priming pan beneath. The steel is normally attached to a spring but here it is on the end of a long arm in order to reach back over the cylinder. In the example acquired by Pitt-Rivers, two vertical holes in the barrel attachment clearly show where the arm would have been screwed on.

All the chambers were loaded with powder and balls, and each pan filled with priming powder at the same time, after which the square pan covers that ran between the grooves on the cylinder were slid shut. The chamber at the top was the one that fired and that pan cover had to be removed manually before firing. After firing (note there is no trigger guard), the shooter pulled the cock to rotate the cylinder and position the next chamber which was held in place by a ‘plunger’ locking into a tiny circular recess in each chamber.

Detail of the ball-butt. Copyright The Board of Trustees of the Armouries. XII.4745

Such early revolvers all suffered from misfires and accidents when the chamber was not precisely lined up with the barrel. A considerable degree of gas leakage from the breech also affected range and velocity. For this reason they were never mass-produced. Annely would have run off a limited number from this pattern. The Pitt Rivers Museum and Royal Armouries examples are bothers but not a pair. Many single-shot pistols (especially duelling pistols) of this era were sold as pairs to guarantee the owner two shots in quick succession. The multi-shot capacity of this gun was intended to overcome this necessity, making it a lone weapon.

In fact, so rare and unusual is this gun that even without its mechanism it was stolen from the Museum in the 1960s, substituted by a crude copy commissioned by the culprit to be made in Hong Kong. Fortunately the police recovered the original and both are now displayed together in the Museum.