'... Before long, we came on to Pitt-Rivers' ground, all the gates bright blue with yellow tops, like the covers of his archaeological pamphlets. I thought them ugly, but when we were driving back, they seemed nice, when one had spent all day in their fairyland, and seen the King of the place with all his magic things about him.' [Drower, 1994, quoting Hilda Petrie from a visit to Rushmore in 1898]

Pitt-Rivers' not only publically displayed his collections at London and Oxford (founding collection) and Farnham, Dorset (second collection), he also kept and displayed objects at his homes. This page gives further information about these homes and evidence of this part of the disposition of his collections. It is divided temporally, as his financial circumstances changed so much in 1880 when he inherited the estate from his great-uncle.

See here for photographs of some of Pitt-Rivers' homes from 1827-1900.

Before 1880

This link gives information about all of the residences Pitt-Rivers lived in up to 1880. There were at least 12 of these, the most important being the houses he lived in in London: including Chesham Street, 10 Upper Phillimore Gardens, 30 Sussex Place, Onslow Gardens, and 19 Penywern Road. Edward Burnett Tylor in his entry for Pitt-Rivers in the Dictionary of National Biography remarks that these houses were full of objects from cellars to attics. Unfortunately however, there is not known to be a catalogue or list of the items from these days except for those which ended up being transferred to the University of Oxford, so we shall never know about the majority of things Pitt-Rivers chose to be surrounded with in his own home before 1880. Here is an account of the items known to have been located at Penywern Road (according to the catalogue of the second collection), this must be a small percentage of the overall number.

Pitt-Rivers lived in several houses in London but they were all in western London or on the west side of central London. Here are some details about the kinds of houses, and areas, he was living in before 1880.

Brompton Crescent, Brompton

This was a rented house lived in for a short time between returning from Malta and staying with his parents-in-law in central London at Dover Street, and moving to Clapham. British History online says:

The development produced thirty-four houses in Brompton (now Egerton) Crescent ... The houses in Brompton Crescent, made up of twenty-four in the crescent proper and two short return ‘wings’ of five houses each, were numbered 26–59 (consec.) in continuation of the numbering of the existing late-eighteenth-century houses opposite to the new crescent (see page 90). This numbering was retained both when the latter houses were demolished in 1885 and when the street was renamed Egerton Crescent in 1896 after the Honourable Francis Egerton, one of the Smith's Charity trustees. ...

Park Hill House, Clapham

Presumably Park Hill House was on Park Hill in Clapham, SW4. This is the furthest he lives outside central London. It is quite close to Clapham Common. He lived there for at least 2 years in 1858 and 1859 according to Thompson (1977: 123).

10 Upper Philimore Gardens, Kensington

Pitt-Rivers lived here in 1866-7. [Thompson, 1977: 123] It is located just north of, and parallel to, Kensington High Street. This street is now one of the most expensive in London. Pitt-Rivers lived on the south side of the road. According to the Survey of London volume 37: Northern Kensington 'Joseph Gordon Davis was himself responsible for most of the larger houses in Phillimore Gardens and Upper Phillimore Gardens'. The same source says:

The enumerators' books for the census of 1861 give an indication of the kind of people who were attracted to the new development. Returns were received from fifty-seven houses, just over a quarter of the number eventually built under the agreement with Davis. The occupants of the new houses were generally members of the substantial Victorian middle class and on average there were between two and three servants to each household. A considerable number of residents belonged to the professions. As might be expected there were several solicitors and barristers, including Charles Clode, the solicitor to the War Office, at No. 47 Phillimore Gardens, as well as surveyors, doctors and one dentist. Perhaps the most remarkable concentration was of artists, seven occupiers describing themselves as such; five lived in Upper Phillimore Gardens, the most noteworthy being Henry Tanworth Wells (at No.9), Frank Dillon (No.13) and William Duffield (No.4). Four men described themselves as clerks, but the size of their households indicated that they are probably in positions of considerable authority. There were a few army and navy officers, mainly retired, including Captain William Hutcheons Hall) at No. 48 Phillimore Gardens . Few individuals declared that they were living on unearned incomes, and those that did were mostly widows, although two men described their occupation simply as that of 'gentleman'.'

Find this account here. Frank Dillon was trained at the Royal Academy schools and was a widely travelled topographical painter, painting in Egypt and Japan. It is tempting to see him as an influence on Pitt-Rivers' artistic tastes but there is no evidence that the two men ever met.

30 Sussex Place

now known as Launceston Place is in Kensington. As he is supposed to have lived in both Sussex Place and Onslow Gardens in one year (1878), they may have been temporary rented lodgings before he purchased Penywern Road. As shown below, Penywern Road houses were built during the 1870s and he may have had to await the completion of his house(s). According to the Survey of London volume 42, Kensington Square to Earl's Court:

Kensington New Town is a name in only limited current use. Today it refers loosely to a fashionable district of predominantly stuccoed housing South of Kensington Road, west of Palace Gate and Gloucester Road and north of Cornwall Gardens. The early-Victorian pattern and character of this district derive from the history of two estates, which are called in the ensuing account by the names of their freehold owners at the time of their main building development. To the east is the compact Inderwick estate of six and a half acres, covering the area of Victoria Grove, Launceston Place, the west side of Gloucester Road between Kynance Place and Canning Place, and the south side of Canning Place. Built up neatly and efficiently between 1837 and about 1843, this was the area originally denominated Kensington New Town, a name first encountered in 1841. ... Launceston Place was known as Sussex Place until 1883. It was the last of Inderwick's new streets to be finished, its houses not all finding residents until 1846. The buildings here are mostly semi-detached villas, each side having its own distinctive design. On the earlier, western side the typical features are the round-headed recessed porches and square two-storeyed bays; on the eastern side the design is holder, with squarepiered, double-height porches of some originality and pairs of narrow round-headed windows like those in Victoria Grove. The last house on the west side (No. 22) has a little circular, lead-capped turret—perhaps a slightly later addition. .... But two leases were granted to building tradesmen, one in November 1842 to William Laurence of Kensington Church Street, plumber and glazier (No. 30) ... Four of the estate's residents in 1851 found their way into the Dictionary of National Biography: the Reverend James Booth, educationist, mathematician and discoverer of the ‘Boothian co-ordinates’ at No. 7 Launceston Place; ... Thomas F. Marshall, painter, at No. 11 Launceston Place;... Between 1862 and 1865 the heretical Bishop Colenso, home on furlough from Natal to defend and promulgate his views, lived intermittently at No. 23 Launceston Place. By 1881 this street had fallen from social grace and was inhabited by smaller families of an apparently lower status; at No. 14, the activities of a ‘psychopathic healer’ perhaps enlivented the street.'

See here to find a longer account.

Onslow Gardens

See above. Onslow Gardens is in Kensington parallel to but between Old Brompton Road and Fulham Road. See Thompson, 1977: 125 for the reference to him living in these two places. According to the Survey of London volume 41:

Building in Onslow Gardens was under way by 1863, the first occupants moved in during 1864, and by 1878 all of the houses in this complex pattern of streets had been completed and occupied. ... Onslow Gardens and Cranley Place and the Italianate houses in Cranley Gardens have elevations of grey stock brick with stucco dressings rather than the completely stuccoed façades previously favoured by Basevi elsewhere on the estate and actually specified in the building agreement of 1844. ... The first houses to be built in Onslow Gardens, Nos. 1–8 (consec), which were at first called West Terrace, Onslow Square, introduce cement balustrades to the balconies, canted hays to the end houses of the terrace, and three windows to a floor in each house front, in contrast to two in Onslow Square. Their frontages are wider (twenty-five feet compared with twenty to twenty -four feet generally in the square), but, with the exception of Nos 26–33 (consec.) Onslow Gardens, all of Freake's subsequent houses on the estate are three windows wide ... Onslow Gardens were still in the early stages of building in 1871 and only twenty houses had what appears to be their normal complement of occupants on the night of the census. There were 175 inhabitants in these twenty houses (an average of 8.75 per house), of whom 106 (5.3 per house) were servants. The largest household was at No. 41, where a thirty-five-year-old stockbroker, his wile and three children were attended by nine servants. At the top of the social scale among the householders were a dowager baroness (Lady Monteagle at No. 17, A, whose grandson, the second Baron, was living with her) and two sons of earls, one describing himself as a landowner and the other as a late captain of the First Lite Guards. There was one other landowner and three other army officers, including a retired colonel who was a Justice of the Peace for Northamptonshire. Another occupant was late assistant military secretary to the Horse Guards. Two householders held high public office, the Accountant General of the Court of Chancery and an Assistant Secretary to the Treasury, and two had retired from the Indian civil service. Of the remainder, two lived on income from securities or a jointure, one was the stockbroker mentioned above, and one a ship and insurance broker; the others were a barrister, a clergyman (who was also Secretary to the Church Missionary Society), a newspaper proprietor (William Reed) and the historian J. A. Froude, who described himself as 'Man of letters' and lived very comfortably with his wife and two children and seven servants at No. 5.'

You can find a longer account of the street here.

19 Penywern Road, Earl's Court, London

According to 'The Survey of London: volume 42 Kensington Square to Earl's Court' (1986: Hermoine Hobhouse) accessed via British History Online:

'The formation of an east-west road between Earl's Court Road and Warwick Road in continuation of Eardley Crescent to the west of Warwick Road was projected in 1868, and when building began in the new road in 1873 it was simply regarded as an extension of Eardley Crescent. The Welsh name Penywern was adopted shortly afterwards at Lord Kensington's request. ... When building began in Penywern Road late in 1873 Harris, initially assisted once again by Scott, used essentially the same house-type he had employed in Earl's Court Road, that is houses of three main storeys above a basement with Doric porticoes and bay windows up to the first floor. Their facades are of stock brick with plain stucco window-surrounds and have a cornice and balustrade at roof level. An attic storey within the roof has roundheaded dormer windows set flush with the balustrade. The only slightly unusual features of these very ordinary Italianate houses is that the porches are enclosed and that stone or cement balustrading is used to protect the areas rather than iron railings. ... At that point, in about September 1875, Harris changed from this type of house to one with a full fourth storey crowned by a secondary cornice and balustrade instead of attics, the rest of the elevation remaining unaltered. The succeeding houses in Penywern Road [including no. 19] are of this type and were built over some four years. ... At the time of the census of 1881 fifteen houses in the street were still unoccupied and there was a mixed pattern of occupancy in the remainder with two already being used as boarding-houses. Nevertheless, besides the annuitants, lawyers, clerks, and military men who formed the core of the population of Earl's Court, several merchants, a stockbroker, a shipowner and a railway contractor lived in the street. Sir Norman Lockyer, the director of the Solar Physics Observatory at South Kensington, had purchased No. 16 in 1876 for the remarkably high price of £2,700, and continued to live there until his death in 1920. The archaeologist and anthropologist, Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers, lived in the street for a much shorter time, between c. 1879 and 1881, but he occupied both Nos. 19 and 21 and had eleven servants.

Note that Pitt-Rivers seems to have acquired both nos 19 and 20 in Penywern Road and was probably running them as a single property. His last will and testament makes it clear that he still maintained the leasehold on these properties which were 'now used as one house'. They were bequeathed with the bulk of his estate to his eldest son Alexander.

After 1880

It seems that Pitt-Rivers probably remained in Penywern Road for a short time after he inherited the estate from his great uncle. His main London residence after this date was at 4 Grosvenor Gardens.

4, Grosvenor Gardens, London SW1.

He inherited this house with Rushmore in 1880. As this was in a much more salubrious area than his own house in Penywern Road he must have decided to move his main London residence there quite quickly. Pitt-Rivers' residence here from 1881 to 1900 is marked by a blue plaque (no. 149) first erected in 1983. See here for more detail. Grosvenor Gardens was in the Belgravia area of central London. Like most rich people in Victorian England Pitt-Rivers would spend several months a year in London and other months at his country estate. Pitt-Rivers inherited this property at the same time as Rushmore in 1880. Grosvenor Gardens was described in 1878 as

At the bottom of Grosvenor Place, and reaching to Buckingham Palace Road, is a large triangular piece of ground, intersected by a part of Ebury Street, and covered with lofty and handsomely constructed houses, known respectively as Grosvenor Gardens and Belgrave Mansions. On the east side of this triangular plot is Arabella Row, one side of which is occupied by the royal stables of Buckingham Palace, which we have already described. [Edwar Walford, 1878 'Old and New London: volume 5

The Survey of London volume 39 says:

All of these works as built betray the hand of Thomas Cundy III working untrammelled by the restrictions of previous estate policy. Grosvenor Place itself had a complicated history and was the last of these improvements to be undertaken, but for Grosvenor Gardens, initiated in 1863, Thomas Cundy III provided designs for the street fronts; behind these, highclass builders were allowed to proceed much as they pleased. Cundy's elevations here were of a French-style Second Empire character and of an elaboration and colourfulness hitherto unknown in London terrace architecture, with tall mansards and pavilion roofs, lavish stone dressings, and plenty of red brick, terracotta and polychrome slatework. Though his inspiration was no doubt the New Louvre, mediated through such recent buildings as Burn's Montagu House and Knowles's Grosvenor Hotel, Cundy showed that he had learned something too from the proponents of Advanced Gothic. ...

Find out more here.

Grosvenor Gardens was part of his inheritance. It was presumably furnished when he acquired it, so he must have had a substantial amount of furniture and objets d'art by this stage. Unfortunately we only know the details of the items acquired after 1880 and listed in the 9 Cambridge University Library volumes. The proportion of objects displayed or stored in these locations can be found here.

It is clear that in the 1890s Pitt-Rivers spent increasing amounts of time at his country estate in Rushmore and that his children often lived at 4 Grosvenor Gardens, though correspondence for Pitt-Rivers is still often directed there [see various letters from his children, giving this address, in the S&SWM PR papers].

Grosvenor Gardens was rented out to a Mr Hughes in 1895 and in 1896 it was rented to Lord Wolseley. [I am grateful to Rachel McGoff for pointing this out, as it is at various with the information in Bowden, 1991 but based upon Pitt-Rivers correspondence in S&SWM Pitt-Rivers papers B397] He owned this house until his death when it was bequeathed with the rest of his estate to his oldest son, Alexander.

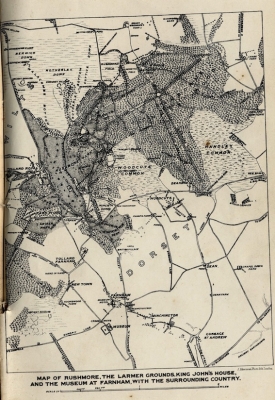

Rushmore

Pitt-Rivers inherited Rushmore as part of his estate. It was a large house of some fifty rooms and there was a surrounding estate of some 27,000 acres. Bowden suggests that it was 'one of the largest held by an untitled man in the whole of Britain and was considerably larger than those held by many noblemen'. [Bowden, 1991: 37] The house and estate were in Cranborne Chase, on the borders of Wiltshire and Dorset, between Salisbury and Blandford Forum.

A History of the County of Wiltshire, volume 13, (1987: Crowley, Freeman, Stevenson) describes Rushmore as follows:

Rushmore Lodge, standing in the 15th century was repaired in 1546 and replaced in the early 17th century. Part of the 17th-century lodge was demolished and the remainder used as offices from the mid 18th century, when Rushmore House was built nearby. The house, of c. 1760, was perhaps the central part of the ashlar-faced main block of that standing in 1984. In the early 19th century a southern extension was built with, to the south, a pair of two-storeyed canted bay windows and between them a front of three bays. Similar windows were later added on the east and west sides of the extension, and a northern wing of the house was replaced by a service range. The interior was much altered for A. H. L.-F. Pitt-Rivers after 1880. Philip Webb was consulted about some of the alterations and the decoration is reputed to have been by Morris & Co. Lands around the lodge, presumably including Rushmore, were imparked in the early 17th century. In the 19th and 20th centuries no clear boundary existed between the park and the surrounding woods. Apart from Rushmore House there were few buildings in the park in the late 18th century. Park House was built in the early 19th century, and in 1839 there were cottages 500 m. north of it. New gardens around Rushmore House were planned after 1856. It is not clear whether those plans took effect, and in the 1880s and 1890s many changes were made to the grounds. The straight drives through the park and Chase Woods were probably made at that time, and cottages north of Rushmore House and lodges in 16th-century style at the northern, north-eastern, and southern park gates were built. A small chapel in similar secular style was built west of the northern gate in 1887. The principal, northern, gate and perhaps some buildings were designed by Webb. Kitchen gardens had by the mid 1880s been laid out 500 m. south-east of the house. Then or later they were enclosed by a high red-brick wall; circular turrets with conical roofs stood at three corners and a viewing platform, looking south-east, at the fourth. From 1893 A.H.L.-F. [sic] Pitt-Rivers maintained a menagerie within the park, chiefly in paddocks near North Lodge. Attempts to acclimatize foreign animals and birds, including reindeer and white peacocks, were largely unsuccessful, but experimental breeding produced unusual crosses, for example of yaks and indigenous domestic cattle. Like the Larmer Grounds in Tollard Royal the menagerie was open to the public.

Find a longer account of the house and surrounding area here. Pitt-Rivers seems to have decided to improve Rushmore as soon as he inherited it. According to Caverhill:

"General Pitt-Rivers wasted no time in making improvements to the interior of "this not beautiful mansion from an architectural point of view but commodious - containing some fifty rooms," (Pevsner, 1950). The interior of the building must have resounded to the noise made by the carpenters who were engaged to install the oak panelling of the main hall, stairway and the square landing on the first floor. Between four and five thousand pounds were spent on the work between 1882 and 1883 and an inscription carved on a panel going up the stairs bears witness today of its construction.' [Caverhill, n.d.: 21]

It is clear from the correspondence that survives in Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum Pitt-Rivers papers that he had a large domestic staff at Rushmore, there are letters seeking references for senior staff like butlers and there is also a letter giving a reference for a Head Gardener, called Robert Stanley, who Pitt-Rivers says was in charge of 40 men working at Rushmore. [L1441, S&SWM PR papers] Another letter makes it clear that as was common for someone with Pitt-Rivers' income and status, he employed both a butler and footmen [see for example L1456, his past first footman who had worked elsewhere for 6 years seeking to return as his butler].

Today Rushmore is a school, Sandroyd.

It is clear from the catalogue that Pitt-Rivers' chose to display a large proportion of his collection at Rushmore. There were several places that were chosen for more formal displays, principally the various galleries (like the so-called music gallery) and also the corridors. Other areas for display were the various rooms in the house, particularly the drawing room and dining room. In addition the room known as the ground floor bedroom seems to have been used for more informal storage. You can find out more about which objects were displayed at Rushmore here.

The Dorset Estate contained other properties, some of which were used to display parts of Pitt-Rivers collection. The most notable were King John's House and the Larmer Gardens (see below). Another house was Hinton St Mary which was used by relatives (like the Reverend Thomas Lane-Fox during Lord Rivers time) and later as a 'dower-house' by Pitt-Rivers' own eldest son. In 1900 the house was extended and renovated (presumably for the next tenant as Pitt-Rivers' eldest son inherited the estate). See here for more information.

Eyewitness account of visiting Farnham Museum and Rushmore in 1898. Find out more about Rushmore here.

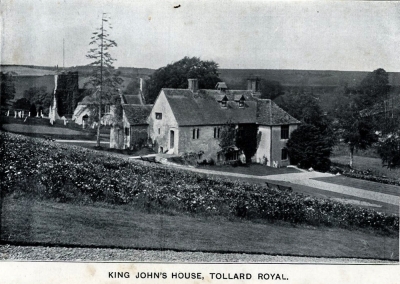

King John's House

Pitt-Rivers used this property to show his fine art collection and even published a book about its contents King John's House, Tollard Royal, Wilts, printed privately in 1890. Thompson describes King John's House thus:

'The name is applied to a building later than John's reign and ... is a transference from the Manor House at Cranborne. The house lies to the south east of the parish church, and consists basically of a first floor hall oriented east/ west, with traces of a contemporary latrine tower at the south west end and a seventeenth century cross range on the east end. Most of the thirteenth century two-light windows were exposed and partly restored by Pitt-Rivers in 1889, when he carried out much work on the structure and excavated the adjoining area. The exhibition in the house was intended to illustrate the history of painting and pottery making. This valuable collection, containing paintings by Giovanni Bellini, Tintoretto and others, was the fine arts section of the main collection housed at Farnham'. [Thompson, 1977: 85]

Find out more about King John's House here. Find out more about what objects are known to have been displayed at King John's House from the catalogue of the second collection here. To find out the full extent of the displays at King John's House see here.

Larmer Tree Gardens

Pitt-Rivers established some pleasure gardens on his estate at Larmer. These included some reconstructed buildings, which still exist today. The gardens were also decorated with statues, which are listed in the catalogues. Please note that the gardens are still open to the public. Find out more about Larmer Gardens here. Find out more about the objects located at the Larmer Gardens here.

Hinton St Mary

After Pitt-Rivers' death items were sent to Hinton St Mary, another property and possibly the dower house for Mrs Pitt-Rivers.

Bibliography for this article

Caverhill, Austin. [undated] Rushmore Then and Now: A short history of Rushmore House and Park, at one time residence of Lieut-General A.H. Pitt-Rivers and now the home of Sandroyd School No publisher [published on the occasion of Sandroyd's Hundredth anniversary]

Drower, Margaret. 1994 'A visit to General Pitt-Rivers' Antiquity 68 (1994): 627-30

Thompson, M.W. 1977. 'General Pitt-Rivers' Moonraker Press.

Images:

Image of Sandroyd School (in what was Rushmore) from http://www.independentschools.com/england/sandroyd-school_1266.html

Image of King John's House from the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum sitehttp://www.salisburymuseum.org.uk/collections/pitt-rivers-collection/king-johns-house-a-royal-hunting-lodge.html

Images of Larmer Tree Gardens taken from http://www.gardens-guide.com/gardenpages/_0550.htm

and

http://pacha-design.blogspot.com/2009_10_01_archive.html

AP, 17 March 2010, updated September and December 2010, updated with information about the will in February 2011.

![Front entrance Sandroyd School (Rushmore), May 2012 [Photo by H. Davison]](../../../component/joomgallery/image/index-view=image&format=raw&type=img&id=1098&Itemid=41.html)