To search the RPR site click here

... one can assume that a movable object normally carries more complex meanings than fixed kinds of décor ... With objets d'art, ... the high value of the material itself was also a consideration ... [b]ut their principal meaning ... was that they served as generic fine art objects. These artefacts elicited 'feelings of the possession of beauty' (Charles Blanc). [Muthesius, 2009: 109-110]

This website concentrates for the most part on Pitt-Rivers' ethnographic and archaeological collections but the Cambridge University Library catalogue of his second collection acquired after 1880 makes it clear that Pitt-Rivers also collected objets d'art and decorative items for his homes. It is clear that Pitt-Rivers shared many of his contemporaries' tastes in interior decoration. This is underscored by examination of the surviving photographs of the interior of Rushmore, his country house, held by Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum. Taste in home decoration is not only for private consumption but also for the public gaze - homes are used not only as dwelling houses but also to entertain guests. They have probably always been used as venues for public display and demonstration of personal taste. Possessions could not only 'show the wealth and cultural aspirations of the owner' but also 'animate conversation and create entertainment'. [Muthesius, 2009: 110]

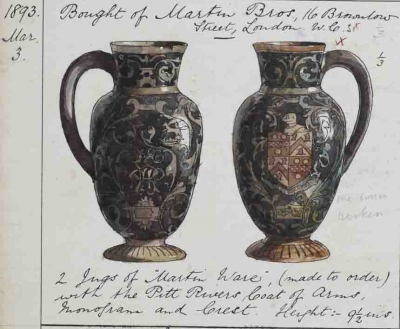

After 1880, when he inherited the means to pay for any decoration in his houses that he wished, he remodelled Rushmore into a fashionable Aesthetic house. Not only did he apparently employ the best known names of the Aesthetic movement in the UK to remodel and decorate the house, like Philip Webb, he also bought the objets d'art that such an interior required - Japanese and Chinese ceramics, fans and furniture, ceramics from the London potters, etc etc. This page seeks to make clear this aspect of his taste, to show how his taste fits into the mainstream of late 19th-century interior decoration.

Unfortunately it is impossible to examine his tastes and styles of interior decoration before 1880 as, so far as we know, this was not recorded. In addition, it is impossible to say what contribution Mrs Pitt-Rivers made to the interior decoration of her home. It is clear that she must have made some - she may even had made most of the choices and the taste for aesthetic or arts-and-crafts interiors may mostly have been down to her. However, it is clear that the CUL volumes record only the items that Pitt-Rivers himself purchased and therefore it is evident that they must have reflected his taste. The catalogue records where some objects ended up in Rushmore and from this it is clear how important public rooms like the Drawing Room were decorated. In addition, it is clear that some items were intended from the start for certain private areas like Mrs Pitt-Rivers' boudoir. These, it must be assumed, reflect her taste.

As well as his taste for ceramic and other objets d'art, another sign of Pitt-Rivers' taste was in the paintings he chose to add to those he inherited in 1880. These are discussed further here. Also significant are the frontispieces he caused to be painted for each of the CUL volumes, like the one shown at the beginning of this article.

It is clear from the catalogue of his library (now held at Cambridge University Library, Add.9455 volume 10) that he was interested in western art, and had an interest in the pre-Raphaelites and aesthetic movement pictures. For example, he owned a copy of the catalogue for an exhibition of 'pictures, drawings, designs and studies' by Dante Gabriel Rossetti held at the Burlington Fine Arts Club (to which Pitt-Rivers also loaned other objects for other exhibitions) held in 1883.

Pitt-Rivers collected a great deal of decorative china and porcelain in his second collection (it is not known if he only started collecting this kind of objet d'art after 1880 as such things are not recorded in any extant record for before 1880). This was a very common form of display and decoration in British homes in the second half of the nineteenth century. As a British writer claimed in the late nineteenth century , 'Next to our pictures our china is our most valued movable decoration'. [unnamed author, quoted in Muthesius, 2009: 109]

Some letters from the end of 1896 makes it clear that Pitt-Rivers continued to be interested in 'arts and crafts' decorative work. On Boxing Day 1896 Percy Scawen Wyndham (1835-1911), a Conservative politician and close neighbour of Pitt-Rivers from Clouds at Salisbury wrote to him to recommend Alexander Fisher. [see L1720 S&SWM PR papers]. Fisher writes to Pitt-Rivers on the same day to say:

4 Warwick studios: Kensington: 26 Dec 1896

Dear Sir,

I have heard with much pleasure from Mrs Wyndham, saying that you would like me to take my work down to your house at Rushmore, to show you. I shall be very happy indeed to do this. And I thought that Thursday next the 30th inst. might be convenient to you: and being the earliest day which I can get my few things together.

One of my pieces of work which I should so much like you to see being one of the best, is now on loan at Sth Kensington Museum. I have asked to be allowed to take it down to you. And Mr Skinner the assistant Director says that if you will be so kind as to write to him asking for it to be sent to you that (if they can persuade the owners to let it go) They will send it insured and ask you to return it in the same manner. If you will be so kind as to do this I shall be so much obliged. I am writing to the owner by the same post.

Believe me Yrs most faithfully

Alex. Fisher

Alexander Fisher (1864-1936) was a silversmith and enameller. He worked at the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts from 1896-8, and believed, as with other Aesthetic movement figures, that every artwork should be created from beginning to end by one person. According to the link given above he made several specimen works to show his mastery of different enamelling techniques. It is not known if Pitt-Rivers commissioned any work by him.

What seems clear from all these sources is that Pitt-Rivers' taste was broadly in line with the then very fashionable Aesthetic movement. He chose 2 of its leading lights to re-model his new country house, Rushmore, which he inherited in 1880:

The interior was much altered for A. H. L.-F. Pitt-Rivers after 1880. Philip Webb was consulted about some of the alterations and the decoration is reputed to have been by Morris & Co. [A History of the County of Wiltshire, volume 13, (1987: Crowley, Freeman, Stevenson)]

Philip Speakman Webb (1831-1915) was an English architect, apparently sometimes called the 'Father of Arts and Crafts Architecture'. He is best known for the Red House, Bexleyheath which he designed for William Morris and Standen in East Grinstead. Webb and Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings [SPAB] in which Pitt-Rivers was also interested. William Morris (1834-1896) was a designer, artist, writer and Socialist. It will be noted that these men were very slightly younger than Pitt-Rivers. It seems unlikely that Morris and Pitt-Rivers would have had much in common given Morris' socialist leanings and Pitt-Rivers' conservatism, but it may have been that very conservatism and belief that change was not necessarily for the best (at least so far as material culture was concerned) that they shared. Pitt-Rivers' strong belief in the slow 'evolution' of material culture being a valuable instructive tool for ensuring that rapid upheaval and revolution was not seen as a valid choice by those who visited his museum and earlier displays can be seen to be in line with Morris' strong beliefs in the value of solid craftsman skills and the need to learn from the past. Pitt-Rivers followed SPAB's interest in the protection of ancient buildings when he investigated and renovated King John's House on his own estate.

The Aesthetic Movement

When delineating the elusive character of the Aesthetic Movement it is hard to avoid straying into the realms of Reformed Gothic on the one hand and the Arts and Crafts Movement on the other [Gere, 2010: 9]

The Aesthetic Movement was the first international design movement to originate in England. One of the movement's key ideas was that 'art should no longer primarily illustrate a story or point a moral but should, on the contrary, be a sensuous visual thing, expressing certain feelings or states of mind'. [Wilson, 2011: 36]

According to Gere, the raison d'etre for the Movement was the cult of beauty. [2010: 16] It grew out of the fascination in the mid nineteenth century for the Gothic and the design reform which started in the 1840s and influenced much art and architecture for the remainder of the century. According to Gere [2010: 9] a central tenet of the Movement was that in a work of art 'every element is essential to the whole'. However, the Aesthetic movement tried to distance itself from all kinds of prescriptive and rigid pronouncements regarding taste. [Muthesius, 2009: 47] Gere suggests that the Aesthetic Movement:

... was the logical development of Reformed Gothic, blended with japonisme and a further eclectic range of sources from Ancient Egypt, Moorish Spain, Chinese, Indian and Persian art, and English eighteenth-century styles in various guises, a free style in architecture and domestic decoration [2010: 16]

The Aesthetic movement can be seen as a precursor to Art Nouveau. Wikipedia lists the sort of things associated later with the Aesthetic movement in interior design and art:

- Ebonized wood with gilt highlights

- Japanese influence

- Prominent use of nature, especially flowers, birds, ginkgo leaves, and peacock feathers.

- Blue and white on porcelain and china.

It can easily be seen that these are all represented in Pitt-Rivers' second collection. This movement, sometimes also called the Art movement, was intensely popular in London from around 1880. This was convenient for Pitt-Rivers, who appears to have utilised it at around that time, if it is true that he employed Webb and Morris in his remodelling of Rushmore.

There seem to have been several contacts between Pitt-Rivers and strong supporters of the Aesthetic Movement. For example, Christopher Dresser corresponded with Pitt-Rivers several times, citing his displays at South Kensington Museum before 1884 as an inspiration to his work on ornamentation. See letters from him transcribed here (the letters are part of the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum’s Pitt-Rivers’ papers).]

South Kensington Museum

Pitt-Rivers displayed his first collection (which later formed the founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford) at South Kensington Museum from 1878-1885. This Museum was an integral part of the spread of aestheticism in England. The museum 'promoted the home as a work of art', and

... [and] was responsible for creating public interest in the wider artistic milieu. Its purpose, to provide inspiration to designers and manufacturers and to improve public taste, has a direct relevance to 'artistic' taste in home design and decoration. [Gere, 2010: 60]

It is possible that Pitt-Rivers developed his taste for the typical products of Aesthetic veneration from this period.

National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry

L588, one of the Pitt-Rivers papers in Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, suggests that Pitt-Rivers had agreed to give a paper at the first meeting of the Association at Liverpool in 1888. Unfortunately L598 makes it clear that Pitt-Rivers withdrew his offer and did not speak even though the promise of a talk appeared on the agenda for the meeting. This was presumably because Pitt-Rivers was so slow to respond to the organizers' pleas for the finished paper. The organizers end the letter 'We had looked forward to the criticisms of so valuable and important an authority as yourself'.

Burlington Fine Arts Club

Pitt-Rivers appears to have been a member of this Club, a gentleman's club for men interested in the arts. In November 1888 he asked the Club to be 'furnished with the Catalogues of the past Exhibitions of the Club'. [see L587 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum Pitt-Rivers papers] As members received these catalogues at no cost when issued it would seem that he joined the Club at about that date. It seems to coincide with an increased interest in art as shown by his belonging to the National Association for the Advancement of Art (see above).

Bibliography for this article

Gere, Charlotte. 2010 Artistic Circles: Design and Decoration in the Aesthetic Movement London V & A Publishing

Muthesius, Stefan. 2009. The Poetic Home: Designing the 19th-century Domestic Interior London: Thames and Hudson

Wilson, Simon. 2011, 'In the realm of the senses' RA London: Royal Academy p. 36

AP, March 2011.