To search the RPR site click here

It is possible to argue that one of the most interesting aspects of Pitt-Rivers life was his death, and this article argues just that.

Death-related artefacts in Pitt-Rivers collections

There is no evidence that Pitt-Rivers had a strong interest in death during his life. Through his collections and his archaeological explorations, he was aware of the myriad solutions that different cultures had employed for the treatment of the dead. As an archaeologist he was also very familiar with the idea of grave goods (items buried with bodies for prestige, or the after-life). Some of the items in his collections directly relate to these subjects. He is known to have donated a total of at least 19,605 artefacts to the University of Oxford. Of these the Museum categorises 254 as being related to death in some way, of which nearly half (119) are from England. This is a relatively small number but many of the 254 artefacts are interesting to specialists. It is unfortunate that he never produced a full catalogue of the collection acquired before 1880 (which eventually came to Oxford) although this had been his original intention. In 1877 he published parts I and II (in a single volume), which covered the weaponry series on display. The second half of the catalogue would have given us Pitt Rivers' own account of the parts of his collection which related to death.

Pitt-Rivers published journal articles about grave goods as part of his reports on excavations he had carried out (for example, Pitt-Rivers, 1876; 1877). However, he never really wrote about the treatment of the dead as he did on subjects like warfare and evolution of design (which were obviously the subjects closest to his heart). Such was the depth and breadth of his collections that it would have been impossible for him to publish on every aspect of them. There are many parts of this collections that are more numerous than those artefacts which relate to death, and these are equally lacking in any public discussion by their owner.

Pitt-Rivers’ religious beliefs

It is interesting to note that many of the artefacts in his collections deemed to relate to death were classified by Pitt-Rivers as 'religious emblems' but later, after transfer to the ownership of the Pitt Rivers Museum, were often seen as 'charms and magic', or else as more mundane demonstrations of mode of transport or as 'Pottery, Ancient Wheel-made'. This downgrading of the religious aspects of the treatment of the dead, and grave goods suggests that Pitt-Rivers himself might, in fact, have viewed them in a more religious light than did the people who cared for his collection after 1884. Unfortunately, he did not record many of his thoughts about death and even his religious beliefs are uncertain. In one of the few instances (an unpublished, and probably publicly unread, draft section of a lecture given at Whitechapel in 1875), he stated:

What then if we do find that religion is subject to the same laws of evolution as all other human ideas. Are we to infer from this that we can see God in nothing, or may we not rather infer that we may see him in everything instead of peeping at him through the narrow chinks & crevices which have been prescribed for us during an ignorant age. [Pitt Rivers Papers, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, P42 cited in Bowden, 1991: 12]

Just over a decade later, in an address to the Archaeological Institute in Salisbury in 1887 he said:

... I cannot myself see how human conduct is likely to be affected disadvantageously by recognizing the humble origin of mankind. If it teaches us to take less pride in our ancestry, and to place more reliance on ourselves, this cannot fail to serve as an additional incentive to industry and respectability. Nor are our relations with the Supreme Power presented to us in an unfavourable light by this discovery, for if man was created originally in the image of God, it is obvious that the very best of us have greatly degenerated. But if on the other hand we recognize that we sprung from inferior beings, then, there is no cause for anxiety on account of the occasional backsliding observable amongst men, and we are encouraged to hope that with the help of Providence, notwithstanding frequent relapses towards the primitive condition of our remote forefathers, we may continue to improve in the long run as we have done hitherto. [cited in Thompson, 1977: 120]

This passage would support a view that he had some religious beliefs but that these did not necessarily entirely accord with organized religious practice of his day. However, he was certainly interested in religion as a topic of conversation as several accounts can verify (see the section on 'Personality' in his biography on this site).

Pitt-Rivers' attitudes to an afterlife are also unknown. He seems to have attended some séances, as was quite common for someone of his class and interests in the mid-nineteenth century. As Stocking remarks of Pitt-Rivers, Alfred Wallace and Edward Burnett Tylor's involvement in séances, 'one might say that they were a representative group, ... [of the] professional and intellectual men and women who provided one important segment of the movement's audience'. [Stocking, 1971: 92] Tylor reported that he heard about one medium from Pitt-Rivers:

Of Mrs Basset[t] I had heard twice before ... once from Col. Lane Fox, who was with his wife at a séance at Lady Powlett's. When the phosphoric lights came, Mrs L-F [Lane Fox] let go Mrs Crookes' hand, jumped up & caught the lights & a very human hand[,] which struggled out of her grasp, which of course in the elaborate Medium report became a spirit hand. Mrs L-F has not I think cared much for the business since. [Unpublished ms in Tylor papers, PRM ms collections; cited in Stocking, 1971: 97]

Attendance at séances at this time is not proof of credulous belief, many people (including Tylor) attended in a spirit of scepticism. It is likely that Pitt-Rivers did similarly, or that his wife was interested and asked him to escort her. Pitt-Rivers, as an active member of the Anthropological Society of London in 1868, could have been involved in 'evaluating the claims of the Davenport brothers, visiting American mediums ... the committee of the Society specified a number of conditions for their continued participation; and when these were declined, they withdrew from the investigation'. (Stocking, 1971: 89)

However, even his own great-grandson assumed that he must have been an atheist, perhaps because during the twentieth century it became more commonplace to see a dichotomy between scientific and religious beliefs.[Bowden, 1991: 10] According to Bowden, one of his biographers, he did not attend church regularly (only at major religious festivals, weddings and funerals) but family prayers were said daily at his country house. [1991: 10] In addition, he allowed (or at least, did not refuse) his funeral to take place at Tollard Royal church. A loose adherence to Christianity is, therefore, inferred if not proven.

So much for his life, work and beliefs; how was this reflected in his death?

Pitt Rivers' death and its commemoration

Pitt-Rivers (like many of his contemporaries) endured ill-health for much of his later life. He seems to have suffered from complications brought on by diabetes and often complained in his letters of infirmity impeding his work.[Bowden, 1991: 7] In 1887 he wrote that:

Having retired from active service on account of ill-health, and being incapable of strong physical exercise, I determined to devote the remaining portion of my life chiefly to an examination of the antiquities on my own property [cited in Thompson, 1977: 91]

In 1897 he wrote, in a letter about buying a new property, that 'Alex [his eldest son] is dead against the purchase of the 'Eyesore' at £3000 He says says it is an enormous sum for it ... I think he is wrong in forming so decided an opinion against it, but as I am only going to be here for so short a time, I do not wish, if I can help it, to go counter to his wishes ...' [L1804 letter to Walter Grove dated 27.4.1897, S&SWM PR papers] It seems clear that he was already assuming that he was going to die relatively soon; he adds at the end of the letter that it was written in bed (though it was in fact typed, presumably by his secretary, so he might mean 'dictated').

By 1898 he was writing, 'I am very infirm now, having had diabetes continuously for 17 years. I can hardly do more than go from room to room but I still keep working a little slowly'. [Pitt-Rivers to Edward Burnett Tylor, 7 August 1898 PRM ms collections Tylor papers P11]

His death occurred on 4 May 1900 at his house in Rushmore, on the Wiltshire-Dorset border, at the age of seventy-three. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford has, in its photographic collections, a photograph of him, apparently taken two hours after his death.[Museum accession number: 1998.271.61] The image was obtained from A. Maltby, who is thought to have been an Oxford bookbinder, in 1918. How it came into his hands is unknown. This is the only known version of this image, though there may be others that are not in the public domain.

In the photograph, Pitt-Rivers is lying on his back, covered to his neck with a sheet but with head bare. The photograph shows his full figure. He is obviously lying on his death-bed, as the surroundings are furnished as a typical bedroom of the period. However the room does not appear to be his supposed 'normal' bedroom as shown by Caverhill in a photograph showing a half-tester bed with curtains, elaborately plastered ceiling, tapestries inset into the panelling etc. (n.d.: 27) The death portrait shows a more conventional Victorian bedroom, and a single bed.

Pitt-Rivers looks as if he has been formally laid out. The composition of the photograph conforms with painting conventions for so-called mortuary portraits.[Ruby, 1995: 27-33] Ruby suggests that painted portraits of this type were primarily commissioned as 'private mourning objects'.[1995: 30] Similar photographs of the corpses of deceased loved ones were not uncommon in Victorian times.

Broadly speaking, the photograph could be said to come within the sub-genre of an 'only sleeping' mortuary photograph, in that Pitt-Rivers' eyes are closed, and he is shown in bed. However it does not seem, to the author at least, that any attempt has been made to simulate a sleeping pose. Rather the body has been laid out, and is shown as it would have been seen by family members prior to being put into coffin for transport. However, the covering sheet is rather crumpled and has not been smoothed down, so the photograph (and laying out) do have the appearance of informality. The presentation of the body seems to be for the eyes of friends and family rather than a wider audience.

It is not clear why this photograph was taken. 1900 is rather late for mortuary photography of this kind in the United Kingdom, [1] and the fact that the photograph is quite large and mounted tells us that it was not intended for inclusion in the family album. [Elizabeth Edwards pers. comm.] [2] All this might suggest a very definite different intent but we cannot be sure what this is. His reportedly relatively poor relationships with other members of his family do not suggest that they necessarily would have wanted a photograph of him, post-mortem, as a memento mori or comfort.[Bowden, 1991: 31-36] Also, it is curious that the photograph did not remain in the hands of the family. A mere eighteen years after being captured, it had found its way into the antiquarian book trade. For the author at least, this confirms that the motivation for taking the photograph did not come directly from the family, but probably from Pitt-Rivers himself.

Indeed it seems probable that there was some pre-meditation in the act of photographing Pitt-Rivers' corpse because it took place so soon after the moment of his death. Who did this meditation, who took the photograph, and for what purposes will probably never be known for sure. It is possible, however, to speculate about the identity of the photographer. The possible options appear to be a member of his close family who was a keen amateur photographer, though the identity of one such has not been confirmed. More probably, it was one of his assistants who he employed to work on his archaeological excavations, recording all his artefactual purchases, in a series of volumes, and helping with and illustrating his publications.[Thompson and Renfrew, 1999] The assistants recorded the archaeological digs in a series of photographs (for example, see Bowden, 1991: 132) and would easily have been up to the technical problems of photographing Pitt-Rivers' body. The assistants, though kept at a social distance from the family, lived in Rushmore and were part of the General's household.

The most probable person to be the photographer was G.F. Waldo Johnson who worked with Pitt-Rivers until 1900 and was an adept artist. [Bowden, 1991: 106][Thompson and Renfrew, 1999: 385] This in turn makes it more likely that the General himself suggested that a photograph be taken as he managed the assistants directly. Johnson is described as a 'master illustrator' by Thompson and Renfrew (1999). Their article includes examples of his art (see particularly plates 9 and 10). He illustrated some of the Pitt-Rivers' bound volumes of purchases from Volume 3 onwards. He joined Pitt-Rivers' staff in 1895 and was a dominant force in illustrating his published work. He continued at Farnham Museum (Pitt-Rivers' private museum) after his master's death and was called 'Secretary' in 1901.[Thompson and Renfrew, 1999: 385] Another possibility might be Courtney Shepherd, an assistant who also continued to work at Farnham Museum after 1900. [Thompson and Renfrew, 1999: 385] He does not appear to have had such a marked contribution on the artistic endeavours.

Pitt-Rivers himself may have requested that a photograph be taken, as part of his ‘scientific’ attitude to death; this attitude might be confirmed by his choice to be cremated. It is clear from his writings that he considered him a scientist, one who used material culture to demonstrate the evolution of man; this in turn is likely to have distanced him from conventional religious beliefs and contemporary practices for the treatment of the dead. In addition, he was someone who sought physical evidence for theory and intellectual development; it was not enough for him to theorise, he needed to ‘see’ the ‘evidence’ with his own eyes. He might have considered that a photograph after death showed that death had actually occurred and what the process involved. Pitt-Rivers' on-going interest in acquiring evidence of different cultures' methods of treating the dead (both of their own culture and of enemies) may have influenced the fact that his own laying out was recorded for posterity, even if he did not ensure that his human remains remained intact. It is clear that he wished his human remains to be destroyed by choosing cremation: the only satisfactory way of ensuring this.

If the photograph was intended as a pseudo-scientific record, it is hard to see what the photograph is 'saying', as there is nothing remarkable about it, though of course it is unique (as all portraits must be). It is also unclear who Pitt-Rivers might have intended it to 'speak to'. He was not a Victorian A-list celebrity, though well-known in scientific circles for over forty years. The photograph would not have been created to meet public demand. In addition, the setting is informal and taken very close to the time of death. A more formal portrait would surely have been taken of his corpse in the coffin for such a purpose. I conclude therefore that the photograph must have had some personal meaning as well as public, scientific purpose, for it can never have been conceived to have publication or public interest possibilities. Might the photograph of his body have been taken as a permanent record of his passing, given that his body would be ashes, and he would not have a permanent burial plot (though he would have a memorial)? The photograph was a physical manifestation of his death in the same way that the more usual gravestone would have been. His interest in recording intangible intellectual endeavour by collecting the physical results (that is, by collecting the everyday possessions of other cultures) may be mirrored in the physical need to mark his passing.

Ruby suggests that:

Photographs commemorating death can be seen as one example of the myriad artifacts humans have created and used in the accommodation of death. [1995, p. 7]

From what is known of Pitt-Rivers' character, his social relations and attitudes to religion and science, I would infer that the motivation for the creation of the photograph may well have come from him, that in some way this photograph, rather than being a private record (which Ruby suggests motivates most such photographs), was a record for more public consumption. This inference is, of course, unfairly supported by the fact that the photograph eventually came into a museum collection where it may be consulted by all interested persons, though it has never been put on display, as other images of him in the Museum's collections have been. There is no record of a death mask being taken of him, which would have been another permanent marker of his passing. Perhaps he preferred to employ a newer technology (photography) for this action rather than the more traditional death mask?

Ironically, the painted portrait of John Tradescant the Elder on his deathbed by an unknown British artist in 1638, owned by the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, bears striking resemblance to the Pitt-Rivers photograph. [Ashmolean WA 1898.9; Ruby, 1995, p. 28 Figure 6.) The first similarity between the men, not connected with these portraits, is that they were both major donors of large artefactual collections to the University of Oxford. In the portraits the similarities continue: both the heads are supported by pillows, both men have sheets folded down so that the head is exposed though their chests are covered and both men have their lower jaws bound closed for practical reasons during the laying-out period (Pitt-Rivers' bandage is camouflaged by his beard). The men also bear a physical resemblance, chiefly because they are both relatively elderly and heavily bearded. In fact, Pitt-Rivers spent most of his life clean-shaven (though with heavy side-burns) until he was ordered to grow a beard by his doctor to protect his throat, presumably to offset the effects of the recurring bronchitis he suffered from.

Pitt-Rivers' death was unusual for another reason. He had elected to be cremated and this was carried out in Woking, Surrey on 9 May 1900. Although the first legal cremations in the UK had occurred in 1885, it was still very rare by 1900. Indeed it was not until two years following his death, in 1902, that the Cremation Act was passed by Parliament, giving cremation full legitimacy for the first time. Even by 1918 only 0.3 per cent of funerals involved cremation.[Jupp and Gittings, 1999: 250] Jupp and Gittings state that support for cremation at this time was 'strongest among the upper and middle classes, notably among the literary and scientific intelligentsia', and it seems that Pitt-Rivers was no exception.[1999: 251] It is possible that his knowledge of other cultures' different practices with regard to disposing of the dead, may have made it much easier for him to accept cremation as the sensible option. There is a story in his biography, possibly apocryphal, that he was determined that his wife should also be cremated, shouting 'Damn it, woman, you shall burn'. [Bowden, 1991: 34] In fact, his wife (who long outlived him) and children are buried in Tollard Royal churchyard as they obviously did not share his enthusiasm for cremation.

In contrast to modern practice, he was cremated before his funeral ceremony:

The remains of the late General Pitt Rivers will be cremated in Woking today. The ashes will be brought back to Tollard Royal, and the final ceremony will take place at Tollard Royal Church to-morrow afternoon. [Birmingham Daily Post, 9 May 1900: 4]

The Hebdomadal Council of the University of Oxford on 7 May 1900 appointed Edward Burnett Tylor, Henry Pelham and Henry Balfour (the Curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum) to be present at his funeral as representatives of the University. [University Intelligence: Jackson's Oxford Journal, 12 May 1900: 6] In addition the museum assistant, Harold St. George Gray, who had previously worked for Pitt-Rivers, attended.[Gray, 1953: 5] The funeral took place in Tollard Royal (the nearest settlement to his country home at Rushmore, Wiltshire).

Pitt-Rivers' death was marked by several published obituaries, as was common for people of his class and scientific interests. Obituaries were published not only in the national press but also in the major local newspapers like the Leeds Mercury [12 May 1900: 6], the Bristol Mercury and Daily Post [12 May 1900: 4], and the Northern Echo [11 May 1900]. The obituary for him in The Times of 7 May 1900 described his army career and added:

But it is not for his military career, distinguished though it was, that General Pitt-Rivers will be remembered by posterity. He was only 25 when he began to collect specimens of objects such as weapons, articles of dress, ornament &c., which were brought to England from various savage countries. In choosing his specimens he was guided by the principle of connexion in form, his desire being to illustrate the development of specific ideas among savage peoples and their transmission from one people to another. The result of his patience and scientific enthusiasm was the formation of a collection illustrative of savage life and embryo civilization which is certainly unrivalled in this country and probably in Europe also. [p. 11 column G]

In addition, his passing was marked in a series of learned journals, to most of which he himself had contributed during his life. [Geographical Journal, 15 no. 6: 654; Folklore, 11 no. 2: 185-7 et cetera]

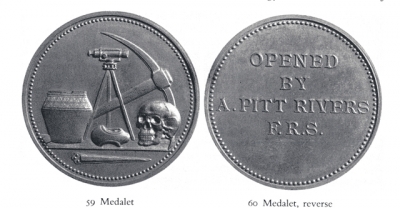

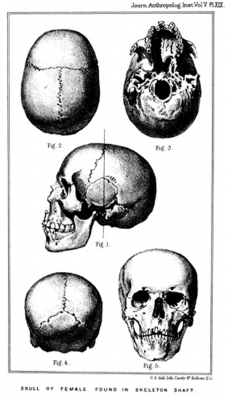

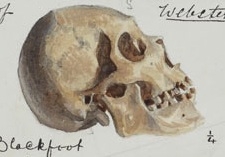

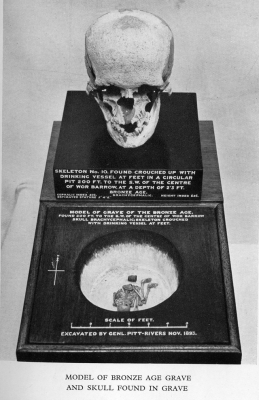

Pitt-Rivers' chosing cremation of his corpse is at variance with his wish to conserve the physical evidence of contemporary and past cultures by collecting them and placing them, in perpetuity in a museum. In the absence of any skeletal remains, his only lasting memorial (apart from his collection at Oxford) was his sarcophagus at the west end of Tollard Royal church in Wiltshire. [Bowden, 1991: 34] This is decorated by motifs of pick axe, surveying equipment, pot and human skull. These are the same motifs as on the medallion (or medalet as he termed it) that he had caused to be made, which he used to place at the base of his excavations before they were filled in. These marked his temporary presence and acted as dating evidence.

The design was created by Sir John Evans; an eminent fellow archaeologist and President of the Numismatics Society in 1880. It is clear, however, that Pitt Rivers chose the components of the design. [Evans, 2006: 964, 965] The presence of a human skull in the design made it particularly appropriate for re-use on the sarcophagus, though it was probably originally chosen for the medalet to reflect Pitt-Rivers' interest in craniological studies rather than a memento mori. Using the same device on his sarcophagus marked his temporary presence on the earth, in the same way that the medalet had marked his temporary opening of the earth during excavations. Pitt-Rivers may not have been able to leave grave goods in his own sarcophagus, but his collection contained many grave goods, especially from pre-Columbian Peru and Egypt but also from his own excavations in England.

The headless body?

A final bizarre twist in the tale. Some sources have suggested that Pitt-Rivers' head was removed after death and deposited in a public collection (for example, see here which suggests, 'He ordered his body to be cremated but left his head to the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons').

Bertrand Russell in his 1937 edition of his parents' letters (he was Pitt-Rivers' nephew by marriage), comments that his grandmother (Pitt-Rivers' mother-in-law) Henrietta Maria Stanley used to say:

"I have left my brain to the Royal College of Surgeons ... because it will be so interesting for them to have a clever woman's brain to cut up.' [Russell, 1937: 18]

Perhaps this gave Pitt-Rivers an idea which he later implemented?

Until January 2012 the authors of this monograph believed that this was based on hearsay but in that month Anthony Pitt-Rivers handed over a typescript of the beginnings of an autobiography that Lane Fox, in 1879 started but did not complete. At the end of the page or so of typescript (prepared by his descendant from his own handwritten version) is a short paragraph:

I wish to pursue a different course in my own case, and that my children should at least have the power of referring back to their family history if they desire it. I do not indeed propose to make a clean bosom of all my innermost thoughts but I desire to write with as little bias as can reasonably be expected of a man when speaking of himself. I have kept no journal, nor being a man of methodical habits and must rely on memory for the past years of my life, but my wife since her marriage has kept a small pocket diary to which I can refer for dates.

For the same reason that I write this, I would wish that if it could be done without inconvenience and without jarring on the feeling of those that I leave behind a post mortem examination should be made of my body and the particulars of my physical constitution recorded by a competent anatomist for the information of my descendants, more particularly the form and peculiarities of the cerebral convolutions, and I should even think it reasonable if it were practicable to preserve the skeleton for comparison with those of any of my progeny who might be similarly minded to have it done.

If Pitt-Rivers continued to hold this desire until 1900 then it does seem possible that the death portrait owned by the museum was taken as a record before post-mortem, and that his head (including presumably his ‘cerebral convolutions’) was removed. It may then have been given to the Royal College of Surgeons for safe-keeping and study, but lost in the second world war. We certainly from this autobiographical fragment know why he would have wanted to do this.

Simon Chaplin of the Royal College of Surgeons, however, has confirmed that there are no records at the collections to support this claim. He suspects that someone has confused him with another eminent archaeologist, William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), who did leave his head to the College in 1942. For further details about the Petrie head, see Ucko (1998). However, an article in the Sunday Times of 22 June 1969, entitled 'A new drum for the General' states:

It seems appropriate that [Pitt Rivers] survived until 1900, and that his skull, which he left to science, was lost when a bomb destroyed the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons.'

Chaplin has stated that although he can confirm there are no accession register entries for skulls which might be Pitt-Rivers', Petrie's skull was not accessioned either when it entered their collections so there is an outside possibility that Pitt-Rivers' skull was once part of their collections. If it were true, then it would yet again be another confirmation of Pitt-Rivers' essential scientific attitude to death, dead bodies and his own corpse. However, the lack of any documentary proof, including no reference in family history or written accounts in archives, and the absence of any physical evidence in the form of a skull, would suggest that it is unlikely to have been true. [pers. comm. 19 January 2008, 27 February 2008]

Conclusion

It seems, therefore, that like a lot of people, Pitt-Rivers had given some thought to the subject of his death before the event. His furious debate with his wife about cremation, obviously legendary among future generations of his family, suggests that matters of this kind were of some importance to him. In addition, several of the commemorative events following his death would have had to be set in motion prior to his death if he were to agree them, especially his sarcophagus and memorial photograph (and the removal of his head for preservation, if this did occur). Because of his long-term health problems he is likely to have had a great deal of notice of his imminent demise and this might have made preparation easier. Although it cannot be proven, it seems like his hand can be seen in the arrangements following his death; they certainly seem unsurprising in the light of his earlier life and work. His lifelong interest in the evolution of design and technology is demonstrated in his death as well as in his collection; he employed the relatively novel technologies of cremation and photography to action and record his death and disposal of his earthly remains. His legacy today is his collection at Oxford (and the continuing scholarly interest in that and his life and work), but he has also left some intriguing clues to one scientifically-minded man's reaction to the universal truth of death.

Notes

[1] Ruby links the decline in public advertising of mortuary photography in the United States by 1900 to a 'shift in public sentiment'. He believes that the practice of photographing the dead continued, but it became less publicly acknowledgeable. [1995, p. 60]

[2] In fact the photograph has been roughly double-mounted but the second mount is intended to support the original mount as the photograph and original mount were obviously bent at some point during its history and almost or entirely split.

Further References

Bowden, M. (1991). Pitt Rivers - The life and archaeological work of Lt. General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers DCL FRS FSA. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapman, W.R., (1981) Ethnology in the Museum, unpublished D.Phil. thesis (University of Oxford).

Evans, C. (2006) 'Engineering the past: Pitt Rivers, Nemo and The Needle'. Antiquity 80, 960-969.

Gray, H. St.G. (1953). [no title] in Anthropology at Oxford: the proceedings of the five-hundredth meeting of the Oxford University Anthropological Society ... Oxford: Holywell Press

Jupp, P.C. and C. Gittings. (1999). Death in England: An illustrated history. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Fox, A.H. Lane (1854) ‘Treatise on Instruction of Musketry’ Hythe School of Musketry

Fox, A.H. Lane (1858) ‘On the improvement of the rifle, as a weapon for general use’Journal of the United Service Institution II, VIII, 453-88

Fox, A.H. Lane (1876) 'Excavations in the camp and tumulus at Seaford, Sussex'.Journal of the Anthropological Institute6, 287-299

Fox, A.H. Lane (1877a) Catalogue of the Anthropological Collection lent by Colonel Lane Fox for Exhibition in the Bethnal Green Branch of the South Kensington Museum, June 1874 London: George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode

Fox, A.H. Lane (1877b) 'On some Saxon and British tumuli, near Guildford' Report of the British Association 116-117

Petch, A. (1998). ''Man as he was and Man as he is': General Pitt Rivers' collections'. Journal of the History of Collections10 no. 1 75-85 Oxford: Oxford University Press

Petch, Alison. (2006) 'Chance and Certitude: Pitt Rivers and his first collection'.Journal of the History of CollectionsOxford University Press pp. 257-266

Pitt-Rivers, A.H.L.F. (1891) 'Typological Museums, as exemplified by the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and hisprovincial museum in Farnham Dorset' Journal of the Society of Arts 40 pp. 115-122

Pitt-Rivers, A.H.L.F. (1906) [edited by J.L. Myres] The Evolution of Culture and other essays Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ruby, J. (1995) Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in AmericaCambridge, Massachusetts / London: The MIT Press

Russell, B. and P. [eds.] 1937. The Amberley papers : the letters and diaries of Lord and Lady Amberley. [2 vols] London: Hogarth Press

Stocking, G.W. (1971) 'Animism in Theory and Practice: E.B. Tylor's Unpublished 'Notes on Spiritualism'' ManNew series 6 (1) pp. 88-104

Thompson, M.W. (1977). General Pitt Rivers: Evolution and Archaeology in the Nineteenth Century. Bradford-on-Avon: Moonraker Press

Thompson, M. and C. Renfrew. (1999) 'The catalogues of the Pitt-Rivers Museum, Farnham, Dorset'. Antiquity 73, 377-392

Ucko, P. (1998) 'The biography of a Collection: The Sir Flinders Petrie Palestinian Collection and the Role of University Museums', Museum Management and Curatorship 17 (4), Appendix A 391-394.

Pitt Rivers manuscript collections, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum

Pitt Rivers Museum manuscript collections, Tylor manuscript collections Box 13

Birmingham Daily Post, 9 May 1900

The Times, 7 May 1900

The Sunday Times, 22 June 1969

'University Intelligence' Jackson's Oxford Journal 12 May 1900

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to gratefully acknowledge the help given to me for this article by Elizabeth Edwards of the University of the Arts; Simon Chaplin of the Royal College of Surgeons Museum; Mark Dickerson, Balfour Librarian; and Chris Morton, Head of Photograph and Manuscript Collections, all of the Pitt Rivers Museum. Thanks also to all the participants in the Pitt Rivers Museum's Work in progress seminar, 1 February 2008.

AP, Prepared 2008-9, revised and completed November 2010