To search the RPR site click here

Made in Japan

Japanese things owned by Pitt-Rivers

According to Lawrence Smith, at the time of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, Japan was still a closed society: foreigners were prevented from entering Japan (except for a small Dutch trading-post at Nagasaki) and Japanese citizens were not allowed to travel abroad. A small number of Japanese goods were included in the Great Exhibition, but were placed in the Chinese section. With the end of Japan's isolation from 1853, information and artefacts began to flow out of Japan towards Europe and America. [1997: 262 et seq]

By 1862 there was a Japanese section of the International Exhibition in London which was highly influential in introducing the British general public to the Japanese aesthetic and material culture. A.W. Franks of the British Museum (a colleaque of Pitt-Rivers) contributed a catalogue of the section and his own personal active interest in Japanese artefacts dates from this time. A small number of the pieces from the exhibition were accessioned by the British Museum in 1862. Franks also bought Japanese objects from the Paris Exposition Universelle for the South Kensington Museum in 1867, including a selection of ceramic objects which had always been a particular interest of Franks.

As Guth explains:

'No single style or medium defines Japonisme, the fashion for all things Japanese that swept Britain, Europe and North America between the 1860s and the first decade of the twentieth century. ... Its varied expressions were rooted in a desire to recuperate the handcrafted values lost in the industrial revolution ... Japonisme celebrated exoticism, sensuality, novelty ... the consumption of Japanese or Japanese-style furniture, ceramics, textiles and metalwork played a key role in the aestheticization of the British home and its inhabitants. The belief that the Japanese lived a life in harmony with nature, with art and beauty overriding material considerations, was fundamental to its appeal ... The flood of imports from Japan following the London International Exhibition of 1862 stimulated among artists and designers a heightened appreciation of materials, techniques, forms and colours.' [Guth, 2011: 110-111]

However, in the forty years of the height of Japanese fashionability, Japanese artefacts and appreciation was not unchanging, as Guth again explains:

During the four decades spanned by the craze the values ascribed to Japan changed, as what had initially been a taste associated with a small avant-garde elite was commercialized by firms such as those founded by Arthur Silver and Arthur Liberty. At the same time, as craft production in Japan became increasingly mechanized and its exports made to accommodate perceived Western tastes, its culture was increasingly decried as decadent.' [Guth, 2011: 113]

In his taste for Japanese artefacts, both for inclusion in his museum collections (noteably weaponry), but also in his private home collections of ceramics and textile etc, Pitt-Rivers was conforming to the prevailing taste of his times but he was also sharing with other connoisseurs the taste for Japanese (and Chinese) high art.

Pitt-Rivers' views on Japanese arts

There is only one recorded instance of him commenting on Japanese arts, in 1884 in a talk he gave to students at Dorchester (Dorset) School of Art:

...This rise in the expression of the feelings appears to me to be the chief characteristic of the influence which Christianity exercised upon Art in Europe. Whatever may be said of modern Art aesthetically there can be no doubt that in the power of depicting the higher emotions it will bear favourable comparison with any of the works of Antiquity. A comparison with Japanese Art will confirm this view. Infinitely our superiors in the use of colours to the extent of placing us in the position of being their pupils, admirable as they are in the execution of all they undertake in the art of carving, yet with all their power of representing the baser emotions of humanity and of emphasising and caricaturing the expressions of fear, hatred, cunning and so forth, amongst the thousands of Japanese carvings and pictures with which this country has been flooded of late years, it is impossible to point out a single example of a human countenance which approaches dignity or gives expression to any of the higher sentiments. And the same observations will apply equally to all Oriental Art.

Overview of Pitt-Rivers' Japanese collection

In the founding collection there are a total of 368 objects known to have come from Japan, in Pitt-Rivers' second collection acquired after 1880 there were 725. Pitt-Rivers therefore owned a minimum of 1093 objects made in Japan, these represent 2.7 per cent of his known overall total collection. These represent the following types of objects*

Ceramics:

Founding collection - 1 [too small a percentage of the total Japanese objects in the founding collection to measure]

Second collection - 187 [26 per cent of the total Japanese objects in second collection]

Vessels:

Founding collection - 6 [1.6 per cent]

Second collection - 203 (of which 150, or roughly three quarters, are made of pottery)[28 per cent]

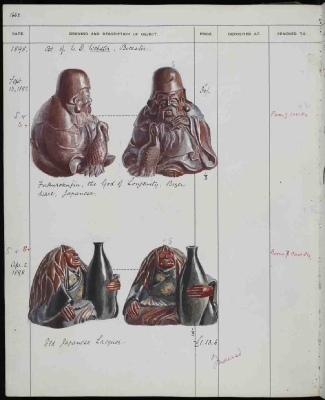

Figures:

Founding collection - 95 [26 per cent]

Second collection - 145 [20 per cent]

Pictures and prints:

Founding collection - 50 [14 per cent]

Second collection - 61 [8 per cent]

Netsuke:

Founding collection - 17 [5 per cent]

Second collection - 11 [1.5 per cent]

Weaponry including sword guards:

Founding collection - 84 [23 per cent]

Second collection - 169 [23 per cent]

*Please note that these types are not exclusive, a pottery figure will be counted under two headings (at least), 'Ceramics' and 'Figures'.

From which it is clear that netsuke were not an important part of Pitt-Rivers' Japanese collections, whereas figures and weaponry certainly were (for the founding collection), and ceramics and particularly ceramic vessels certainly were for the second collection. Pictures and prints represent a significant minority of the Japanese collections.

The earliest known piece acquired by Pitt-Rivers from Japan is 1884.31.23, a piece of armour which forms part of the founding collection and is known to have been part of that collection before 1867 because it is mentioned in his paper, 'Primitive Warfare' page 33 'Plate IV fig 42 Japanese armour composed of chain, plate and enclosed quilted plates - Col. Fox's collection - (a) left arm (b) greaves'. A further 212 objects are known to have been acquired during the 1870s. Most of the other Japanese objects in the founding collection do not have an associated date of acquisition.

The first item in the second collection from Japan was acquired before 19 October 1882 and was a bronze incense burner from an unknown source. The last known acquired objects were three from George Fabian Lawrence in April 1899 (a little over a year before Pitt-Rivers died) - a carved wood mask, and two items from an 'incense game'.

Pitt-Rivers acquired Japanese objects from the following sources:

Founding collection sources of Japanese artefacts

Most sources are not known but the following have been identified:

Eugene Boban of Paris (a dealer)

Alfred Inman (a dealer)

Henry Nottidge Moseley (he probably visited Japan during the HMS Challenger expedition)

Paris Exposition Universelle 1867

Royal United Services Institution (from the museum)

Samuel James Whitmee (another collector)

John George Wood (another collector)

Second collection sources of Japanese artefacts

Andre Block, 101 Wardour Street, London

A. Bonner

James Alexander Butti, 7 Queens Square, Edinburgh

Button, 2 Pall Mall Place / Regent Street, London

Christie's

William D. Cutter, 36 Great Russell Street, London

Messrs Dowdeswell, New Bond Street, London

[Great International] Fisheries Exhibition, 1883

Foster, 54 Pall Mall, London

Franck possibly S.M. Franck & Son, St Mary Axe, London

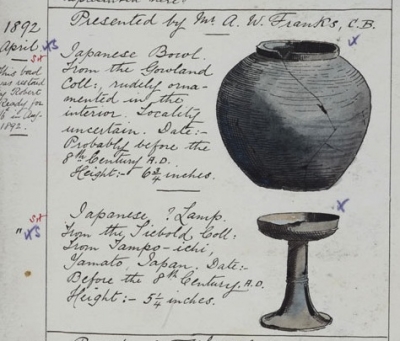

Augustus Wollaston Franks

Henry Grose, 44 St Mary Axe, London / Billiter Street stores

Halstaff & Hannaford, 228 Regent Street, London

Alfred Inman, 17 Ebury Street & 94 Victoria Street, London

Charles Jamrach, St George's, London

Japanese Fine Art Association, 14 Grafton Street, London / 28 New Bond Street London

Japanese Fine Art Depot, 15 Duke Street, Manchester Square, London

Kataoka Masayuki, 32 George Street, Hanover Square, London

George Fabian Lawrence

J. Ramus, 74 Piccadilly, London

Charlotte Elizabeth Schreiber (obtained via Christie's)

Sotheby's

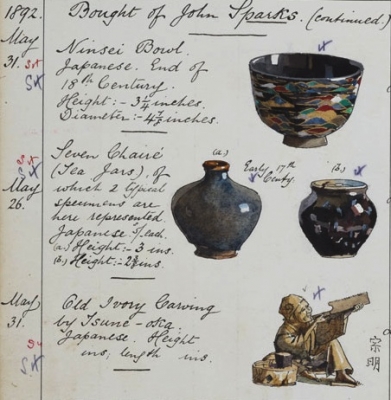

John Sparks, Japanese Fine Art Depot, 14 / 15 Duke Street, Manchester Square, London

William Downing Webster

Samuel Willson, 393 Strand / 7 King Street, St James Square London

Bryce McMurdo Wright junior

The vast majority of the second collection Japanese objects were obtained from dealers or auctioneers.

Alfred Inman is the only dealer who appears to be associated with both parts of the Japanese collection of Pitt-Rivers.

Ceramics

Ceramics were an increasingly important part of Pitt-Rivers' collection, and by the time of his second collection the number of Japanese ceramics is quite striking. They were bought from dealers who specialised in selling such wares, mostly based in London. It seems that some of them were bought as decoration for his homes rather than for museum display, though at least a quarter of them did end up being displayed in Farnham Museum. The ceramic vessels particularly lend themselves to being painted and many of the images of them in the catalogue of the second collection are particularly attractive. It does not appear from the text of the catalogue that Pitt-Rivers considered himself an expert or even a particularly well-informed connoisseur - I think he was probably merely following the contemporary taste for all things Japanese.

By contrast A.W. was particularly interested in collecting 'the different varieties of porcelain which have been produced in the manufacturies of China and Japan'. [quoted in Smith, 1997: 264] His own personal collection of ceramics (including items from Japan) was displayed at Bethnal Green Museum from 1876, at the same time as Pitt-Rivers collection was shown there. By 1887 there were around 800 specimens of 'Japanese pottery' in the British Museum, almost all collected by A.W. Franks [Smith, 1997: 265]

From the 1850s, Japanese potters made a large quantity of items specifically for export, and these were not always of the same high quality as the items which had been exported via the Dutch concession at Nagasaki before 1853. Many enthusiasts for Japanese ceramics could not always distinguish clearly between these lower quality goods-for-export and the higher quality products being produced in Japan at the same time. Smith believed that Franks was sometimes able to distinguish and identify better quality wares although he was hampered by his inability to read Japanese script and the necessity of relying on unreliable Japanese accounts. [1997: 266-7] It is not clear that Pitt-Rivers was as well informed as Franks.

According to Smith, Franks was one of the few British collectors who understood Japanese aesthetics to some degree:

'[Franks] had by then begun to understand the true nature of Japanese taste in ceramics, its eclectism based on the aesthetics of the Tea Ceremony, and its lack of concern for surface gloss: 'In fact the Japanese collector, where pottery and porcelain are concerned, cares little for high finish or elaborate ornament; a rough, sketchy, but picturesque design is far more pleasing to him than the elegant forms and rich decorations we are accustomed to hold in esteem'. [Smith, 1997: 267, quoting Franks' 'Japanese Pottery']

Netsuke

Netsuke (decorative toggles often carved from ivory or wood) were commonly collected by enthusiasts of Japanese material culture in the late nineteenth century. Pitt-Rivers and A.W. Franks were no exception. Franks had a personal collection of some 1400 netsuke which he had begun acquiring in the 1860s, which he first lent, and later bequeathed, to the British Museum. The collection was later catalogued by Oscar Raphael and Frederick Meinertzhagen. Franks believed that his netsuke illustrated 'in a very complete manner the belief, legends, history and manners and customs of Japan'. [quoted in Smith, 1997: 268] Pitt-Rivers had a small collection of netsuke, the larger part obtained by 1884.

Tsuba

Paintings and wood-blocks

Franks had a small collection of Japanese paintings which were later bequeathed to the British Museum. He did not collect wood blocks. Pitt-Rivers followed contemporary taste in buying quite a few prints from dealers. These are listed here.

Archaeological artefacts

Western interest in Japanese archaeology began in the 1870s according to Smith. [1997: 267] One of the key early archaeologists, working in Japan, was William Gowland (1842-1927) who was a metallurgist. The British Museum began to collect pieces almost immediately with a large collection being bought from Gowland by A.W. Franks in 1889.

There are a few clearly archaeological items from Japan in Pitt-Rivers' collections. He obtained a series of stone arrow-heads for the founding collection from an unknown source; they were probably obtained by 1874 (see 1884.135.169-175). He also obtained a stone object described as 'Stone object. Phallus shape with stuck on label with Japanese script and another label 'Japan'' in the 1920s when the founding collection was finally catalogued (1884.140.650). Four similar items (this time oval, flattish oval, shaped like a vessel and lunate) were found unentered (see 1884.140.66, 68, 69, 70). He also obtained a 'magatama' bead (1884.140.67). Again these were from unknown source(s) and date(s), probably before 1874. He purchased a stone arrow-head from Charles Jamrach in 1888. More interesting he was given a bowl (obtained through Franks himself) described as 'Japanese Bowl. From the Gowland Coll: rudely ornamented in the interior Locality uncertain. Date: Probably before the 8th century A.D. Height 6 3/4 inches'. Franks purchased a large collection of archaeological specimens from Gowland in 1889, of which this item might form part. [Smith, 1997: 268] Pitt-Rivers was also given by Franks a lamp described as 'From the Siebold Coll: From Tampo-ichi Yamato, Japan Date Before the 8th century AD Height 5 1/4 inches'. Franks obtained a series of Japanese prehistoric items from the Late Jomon period labelled 'Siebold', this refers to Phillip Frans von Siebold whose extensive collection was brought back from Japan to the Netherlands in 1829. Both of these latter items were given in April 1892 (see Add.9455vol3_p795). Presumably these were pieces that Franks did not want for his own personal collection or for the British Museum.

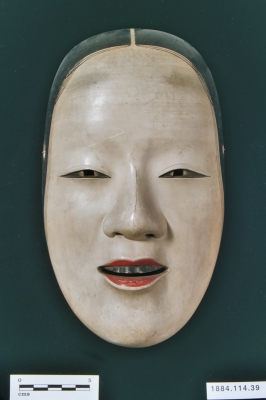

Noh Masks

The founding collection contains a very important set of 52 masks used for Noh theatrical performance. They were all made in the northeast of Japan during the Edo Period, with dates ranging from the early 17th to the early 19th century. It is believed that they comprise a set used by a Noh theatre in the mid-19th century. There are very few such sets in exsistence. The collection includes cloth pouches used for storing the masks and made of textile fragments from fine old costumes. The masks are wooden and variously decorated with gilding, gesso, hair and paint. They include portrayals of demons, heroes, dragons and emperors in a style which combines realism and a 'vacant' expression. Each mask has been signed on the back by the maker, so it has been possible to identify several by the renowned mask-maker Deme Zekan, who worked in the early 17th century. The ancient art of Noh performance combines theatre with music. The masks would have been worn by men in elaborate costumes. To find out more about them, see here.

[Much of the information on this page concerning Japan's history with the West and A.W. Franks collection is based upon the chapter 'The art and antiquities of Japan' by Lawrence Smith, included in M. Caygill and J. Cherry, 1997, 'A.W. Franks ...']

AP, September 2010, amended and augmented twice in September 2011.