Rapier (1892.54.1)

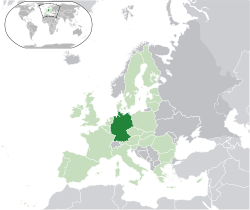

GermanyRapier from Germany (or possibly Spain), Europe. Owned by Baron C. A. de Cosson. Purchased by the Museum in 1892.

GermanyRapier from Germany (or possibly Spain), Europe. Owned by Baron C. A. de Cosson. Purchased by the Museum in 1892.

This early 17th century rapier, with curling counter-guards and knucklebow, may be of Spanish origin. This is because the Latin words, 'PETRUS IN TOLEDO', meaning, 'Made in Toledo' are inscribed on the blade. Toledo was one of Europe's great blade centres in the 16th-18th centuries, along with Solingen and Passau in Germany. However, just as we see imitation products with fake logos today, it was common to find north European swords claiming to be the work of a Toledo smith to increase their market value. This blade lacks the crescent authenticity mark of Toledo so it is likely to be of German origin.

Form and Function

The rapier represents the single most dramatic shift in the way Europeans made and used swords, in the entire history of their use on that continent.

The rapier is a dual-use weapon, adapted to both 'cut and thrust', with a two-edged blade for cutting, and a lean pointed profile for thrusting with the maximum application of force. It came about through Italian advances in manufacturing and hardening steel, which allowed the broadsword to be forged thinner and longer as time went on. This 17th century rapier also has a pronounced fuller - a central groove in the blade. Contrary to popular belief, this is not a 'blood channel' but a structural feature designed to give the blade an arched cross-sectional shape, therefore granting greater strength and flexibility to long, thin blades that might otherwise snap under impact.

The desire for change in the broadsword's form was caused by a revolution in the way Europeans fought with swords - the discovery of the lunging thrust during the Renaissance of the 16th century. Thrusting had previously been fairly ineffectual in European fencing prior to this time, as swordsmen generally wore plate armour. However, with the development of firearms (which were capable of penetrating breastplates), heavy plate armour became more of a burden than a benefit, and people increasingly abandoned it or wore less of it. The advantage acquired by the adoption of the lunging thrust was enormous: swordsmen could increase their effective attacking reach from a little over one metre, to three metres or more. The lunge was developed in Italy, which, in terms of fighting techniques, metallurgy and military technology, was by far the most advanced European culture throughout the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

The rapier also marked a second revolution in European swordplay, the development of parrying - the skill of blocking your opponent's attack with your own sword, rather than a shield or armour. As well as making the sword itself a true dual-purpose weapon, this (again, Italian) discovery produced two major changes in weaponry: firstly, almost all Europeans abandoned the shield, which in turn allowed a quicker and more agile style of fighting to develop. Secondly, all swords began to possess increasingly complex and elaborate guards for the sword-hand, which parrying brought very close to the point of the opponent's weapon. This eventually resulted in the basket-hilted and cup-hilted swords of the 18th century that completely enclosed the hand.

The birth and development of the rapier shows very clearly how the types arms and armour used by a society relate to each other in terms of leapfrogging advancements in attacking weapons and, subsequently, the means to repel them. This relationship is, in turn, dependent on, and determines, the style of military tactics used. In addition to the two changes in the shape of swords, the development of thrusting and parrying with the rapier encouraged the rise of fencing as a martial art, and ultimately, a continuing recreational and Olympic sport.