To search the RPR site click here

Object biographies

Pitt-Rivers was born into the landed gentry, his father was a younger brother of the head of the Lane Fox family. His father died when Pitt-Rivers was a child and his widowed mother moved the family to London. Pitt-Rivers himself was the younger son of a younger son. In 1850 Pitt-Rivers would have anticipated spending his entire life working as a professional soldier.

Although a member of the upper classes at this time was more or less guarenteed an income for life, Pitt-Rivers would probably never have expected to become very wealthy or socially prominent in the normal set of events. Earlier in his life he seems to have relied on his mother to buy his Army promotions for him (for example buying his Colonel’s commission in 1867). However, he was never poor, by his own account he spent up to £300 a year on purchases for his collection in the early years. [Pitt Rivers, 1884 Address delivered at the Opening of the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester January 7 1884: 8]

I am one of the commentators who has been guilty of talking up Pitt Rivers’ wealth post-1880 and thereby, by default if nothing else, suggesting he was not at all wealthy beforehand. This is, of course, an oversimplification. Although Pitt Rivers was infinitely more wealthy in 1881 than he had been before 1880 he had never been poor. His annual income before 1880 was never less than one thousand pounds sterling. This was 'worth' (using the comparator of average earnings, some 600,000 pounds sterling in 2008), not a small sum. Of this, according to his own account, he spent roughly a third, £300 or the equivalent of about £200,000 per annum on objects: ‘... I can ... say that my museum was formed at a time when my means of collecting were very small, and that it never cost me more than £300 a year at most.’ [Pitt Rivers, 1884a Dorchester address: 8] All things are relative, but neither his income, nor the amount he spent on artefacts before 1880, were negligible.

His great luck was to inherit a fortune and large estate from a distant relative in 1880: 'I inherited the Rivers estate in the year 1880, in accordance with the will of my great uncle, the second Lord Rivers, and by descent from my grandmother, who was his sister, and daughter of the first lord. The will was excessively binding, and provided amongst other things that I was to assume the name and arms of Pitt Rivers within a year of my inheriting the property ...' [Pitt Rivers 1887a, [Excavations in Cranborne Chase' vol I privately printed] xi-xiii quoted in Bowden:103] The will of George, 2nd Baron Rivers made in 1823 had stipulated ‘... within the space of one year next after he or they shall respectively become entitled as aforesaid ... shall sign and upon all other occasions whatsoever the surname of Pitt-Rivers either alone or in addition to his or their surname ...’. The London Gazette of 4 June 1880 announced the Royal licence authorizing [Pitt Rivers] to ‘take and use the surnames of Pitt-Rivers in addition to and after that of Fox and bear the arms of Pitt quartering ... and that his issue may take and use the surname of Pitt in addition to and after that of Fox’. [Thompson, 1977: 75] This inheritance brought him the Rivers’ country seat, Rushmore and enabled Pitt-Rivers to upgrade his London home from Earl’s Court to the Rivers’ town house at 4, Grosvenor Gardens. The country estate consisted of about 27,000 acres (according to Bowden [1991, 37] this was ‘... one of the largest held by an untitled man in the whole of Britain’, and in Pitt-Rivers’ lifetime the annual income average a little under £20,000 (the equivalent of around 2 million pounds sterling per annum in the year 2009 based on a computation of relative values based on deflated GDP at http://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/). Pitt-Rivers was now a very wealthy Establishment man, with both status and enormous income. He tried to cement this pre-eminence by petitioning to also inherit the title of his great-uncle, but in this regard at least he was unsuccessful and his only title remained his Army rank, which he used for the rest of his life,being known to his staff and the country at large as 'General Pitt-Rivers'.

His income and his spending on objects moved up a gear when he inherited the estate, the annual income and the name of Pitt Rivers (or Pitt-Rivers) in 1880. As with so many aspects of his life, it is easier to say what Pitt Rivers did after 1880 than it is before. Thompson explains that Pitt Rivers’ annual expenditure was accounted for under 26 headings, and from 1885 onwards there was an itemised item under each heading, the headings varied over the years but in 1881 included: Furniture and Objects bought; Books and maps; Scientific Expenses including subscriptions to Societies, purchase of objects, Excavations and Explorations as well as the more usual home and household expenses, stables etc. According to Thompson there was heavy spending on furniture and art section throughout the period. [Thompson, 1977: 78]

All his biographers seem to agree that Pitt Rivers did not stint himself, particularly after receiving his inheritance, but that he was not a spend-thrift:

‘Pitt-Rivers is sometimes portrayed as a reckless spend-thrift but the accounts certainly do not bear this out ... Once we examine them and find that almost invariably his receipts exceeded his outlay then it is even more apparent that he kept a close hold on expenditure. If therefore he made a major purchase he had a clear knowledge of how this would affect his annual budget.’ [Thompson, 1977: 77]

Neither was he particularly a skinflint, a role which seems to have been reserved for his wife, according to Bowden at least. [Bowden, 1991: 33]

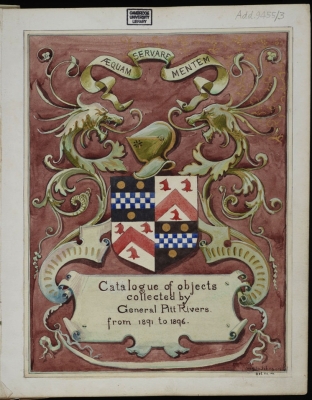

So Pitt-Rivers after 1880 was a senior member of the Establishment with the all important large country estate and income, London town house and place in Society. Because his wealth and high position was unexpected it must have meant even more to him than if he had always expected to inherit. He certainly cherished his position, and liked to be recognized as the senior figure and high ranking officer that he was. Some of his purchases reflect this glory. He was always referred to as the 'General' in the catalogue. He displayed his coat of arms in the frontispieces of the later volumes (see illustration for an example).

His status was also reflected in the high prestige of many of the objects he collected especially the fine art and Japanese ceramics and objets d'art. However, there were other pieces which might also reflect his attitude to his success. Take for example these two jugs which, unusually, the catalogue makes clear were made to order:

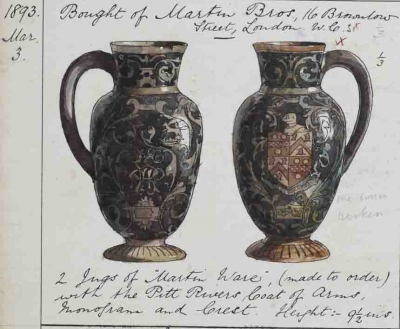

Catalogue Description of object: Bought of Martin Bros, 16 Brownlow Street London WC ... [1 of] 2 Jugs of “Martin Ware’ (made to order) with the Pitt Rivers Coat of Arms Monogram and Crest Height 9 1/2 inches [Add.9455vol3_p890 /1-2]

These were dated 3 March 1893. He was allowed, of course, to bear the arms of the Rivers under his inheritance. The catalogue also states that the jugs cost Pitt-Rivers £6, or £3000 at 2008 values (based on same calculations as above). It seems that fairly shortly after being acquired one of the jugs was broken. The other jug was either displayed (or possibly used) in the dining room at Rushmore, his country house. We will never know why Pitt-Rivers decided to get the jugs made to order but it must in part have been in order to show and demonstrate his personal and family position via the coat of arms, monogram and crest.

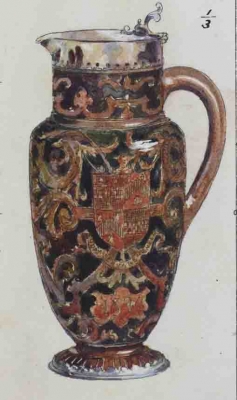

Some two years later in May 1895 he purchased another two jugs from the same potters:

'Pair of Martin Ware Jugs (made to order) with Pitt-Rivers Arms and Crest, initials A.P.R. and date. They have been silver-mounted at the cost of £4.10.0 by Elkington & Co., 22 Regent Street, London. [Add.9455vol3_p1030 /2-3]

The jugs themselves cost £6.6.0 in total. Again he placed the jugs in the dining room at Rushmore. He may have ordered these jugs to replace the original one that was broken?

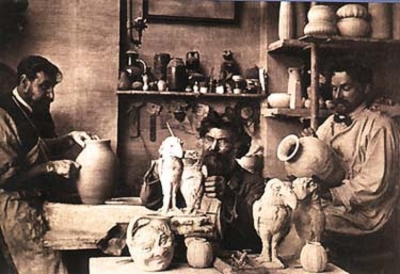

The Martin Brothers were pottery manufacturers in London, they have been 'considered to represent the transition from decorative Victorian ceramics to twentieth century studio pottery in England'. They produced pottery from the 1870s to the First World War, though the pottery continued until 1923 when it closed. Robert Wallace Martin began the Pottery in Fulham in 1873, the business later moved to Havelock Road in Southall. Pitt-Rivers tended to deal with a branch at Brownlow Street. The Martin Brothers specialised in stoneware pottery, specifically saltglaze stoneware. Walter Martin was the pottery wheel specialist, Edwin Martin was the design specialist and Charles Martin ran the shop.

Pitt-Rivers also purchased a great deal of contemporary pottery from William Frend de Morgan, along with large numbers of ceramic objects from Japan and China. Ceramics obviously interested him but in this regard his taste was very typical of his time.

Aside:

Pitt-Rivers seems to have developed an enthusiasm in people who happen to share the surname 'Pitt' after 1880, which may be tied in to his interest in displaying his arms and crest. He made a collection of several items connected to William Pitt and the Pitt Club, see for example Add.9455vol1_p113 /1, Add.9455vol2_p283 /2, Add.9455vol3_p906 /2 and Add.9455vol3_p1023 /3

Bibliography for this article

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Brothers

http://www.ceramicstoday.com/potw/martin_bros.htm

Bowden, Mark 1991. Pitt Rivers: The Life and Archaeological Work of Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapman, William Ryan 1981. ‘Ethnology in the Museum: A.H.L.F. Pitt-Rivers (1827–1900) and the Institutional Foundations of British Anthropology’, University of Oxford: D.Phil. thesis.

Pitt Rivers, A.H.L.F. 1884 [a] Address delivered at the Opening of the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester January 7 1884. J Foster Dorchester, UK

Pitt Rivers, A.H.L.F. 1887. Excavations in Cranborne Chase near Rushmore on the borders of Dorset and Wiltshirevol I Rushmore privately printed

Thompson, M.W. 1977. General Pitt Rivers: Evolution and Archaeology in the Nineteenth Century Bradford-on-Avon: Moonraker Press.

AP, 2009, updated November 2010