To search the RPR site click here

Object biographies

'The collection ... has been collected during upwards of twenty years, not for the purpose of surprising any one, ... but solely with a view to instruction' [Lane Fox, 1875: 293]

'Everything which goes into a collection of whatever kind has done so as a result of selection. The selection process is the crucial act of the collector ...' [Pearce, 1992: 38]

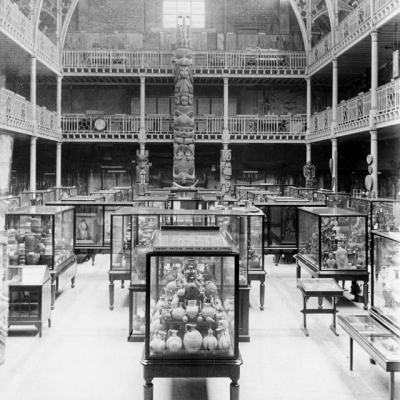

The Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford was founded in 1884 when around 20000 ethnographic and archaeological objects were donated by Lieutenant-General Pitt-Rivers to the University. These formed the founding collection of a museum which today consists of at least half a million artefacts, photographs and manuscripts from all over the world and from all periods of history.

The Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford was founded in 1884 when around 20000 ethnographic and archaeological objects were donated by Lieutenant-General Pitt-Rivers to the University. These formed the founding collection of a museum which today consists of at least half a million artefacts, photographs and manuscripts from all over the world and from all periods of history.

According to Pitt-Rivers' own account, he began collecting in the 1850s, and it seems that 'it occurred to me what an interesting thing it would be to have a museum in which all these successive stages of improvement might be placed in the order of their occurrence'. [Pitt-Rivers, 1891: 118] Very little is known about this early period as he did not record the way his collection grew in any detail (or, at least, such documentation does not survive).

In the early 1870s Lane Fox decided that he wished to show part of his private collection in public. He loaned a small number of musical instruments to the South Kensington Museum for a special exhibition of ancient musical instruments. This led to him agreeing to loan part of his collection to a separate branch of the museum at Bethnal Green for a five year period in Spring 1873, the displays opened in the Spring of 1874 (probably early June 1874) though the majority of this loan seems to have been received possibly at the end of 1873 (this loan is not thought to have been fully documented), smaller loans of further objects continued from 1 January 1874 until the collection left the South Kensington site. Two additional constables were employed to guard the collection. Pitt-Rivers was not alone in displaying parts of his private collection at Bethnal Green: the Wallace collection was first displayed there whilst Hertford House was being altered from 1872-75, and Augustus Wollaston Franks displayed his large collection of Japanese and Chinese ceramics there in 1876. [Macgregor, 1997: 33] The South Kensington Authorities in their Annual Report for 1875 said that Lane Fox's loan 'has proved an attractive division of the Museum'. So far as can be traced there are no extant photographs of the Lane Fox displays at Bethnal Green Museum.

The first record that does survive of Lane Fox's collections is the catalogue he wrote for the part of the collection that he loaned to Bethnal Green Museum from 1874. Unfortunately, the catalogue only covered the weaponry sections of his displays; he intended to produce further catalogues for the remainder, but these were never completed. The first and largest loan consignment was not recorded (or, if it was, has not survived) but it is thought that there must have been less than 10,000 objects in it. The first, smaller, additional set of objects is dated to 1 January 1874, and small additional loans to the Museum carried on being received throughout the decade. Each new loan was associated with a new number expressed as a fraction and, assuming that the second half of the fraction number represents the total number of objects then loaned by Lane Fox to South Kensington Museum, then it seems that before 16 January 1878 there were less than 7456 objects, the total climbed over the decade until it was over 12000 by the early 1880s (12099 in March 1881). The highest fraction numbers ever given were still in the 12000s which suggests that that is a fairly accurate idea of how many objects South Kensington Museum thought had been loaned to them. However, it is clear from records and from the actual objects transferred to Oxford that this was a serious undercounting with some 23,000+ objects actually being transferred to Oxford in 1885. [1] What seems to be missing is the initial consignment. How many of these 23,000+ were displayed at Bethnal Green Museum and South Kensington Museum, and whether some were sent straight from Pitt-Rivers (as he was by then) to Oxford will never be known for sure.

Find out more about Bethnal Green displays here. Find out more about the Lane Fox's collection that was shown at Bethnal Green Museum here.

In 1878, the Museum authorities decided that they wished to move the collections from Bethnal Green to the main museum site, at South Kensington. The objects were housed in galleries on the far side of Exhibition Road from the main museum (further north than the current site of the Science Museum). The exact location of the galleries is unclear but it seems that they must have been parallel to Exhibition Road but set on the other side of the Horticultural Gardens, next and parallel to Queens Gate. According to the frontispiece to the 1879 edition:

'The portion of the Catalogue treated of in the Catalogue already published (Parts I and II) has been arranged, as far as the building will allow, in the same order as before. It begins with Case I (Typical Human Skulls, etc.,) which will be found by the Queen's Gate Entrance at the north end of Room L. The screens begin with No 2 on the EAST Wall of this room, and follow in consecutive order, bearing the same numbers as in the Catalogue to No. 39 in the adjoining room (K). Deviations from this order are indicated on the walls. The portions of the Collection shown in cases in the middle of the Galleries and on the WEST wall will, it is proposed, be treated of in Parts III and IV of the Catalogue, to be published hereafter (see note on page vii).

Page vii: Parts III and IV will be published hereafter, and will relate, the former to modes of navigation, representative arts of savage and early races, ornamentation, personal ornaments, pottery and substitutes for pottery, tools, deities, and religious emblems, clothing and weaving, fire-arms, and Illustrations of the modes of hafting stone implements. Part IV, will be devoted to the pre-historic series, and will include natural forms, simulating artificial forms, illustrations of forgeries and modern fabrications, palaeolithic implements, neolithic implements, bronze implements, and iron implements, with the stone implements of modern savages, adapted to the illustration of those of pre-historic times.

Again, no photographs of the Lane Fox displays at South Kensington Museum appear to have survived (if they were ever taken). The South Kensington Museum displays remained until 1884 when the slow process of transferring them to Oxford began. Eventually the authorities there had to close the displays before transfer began in order to clear the objects into one space so that an alternative use for Rooms L and K could begin. When the objects were actually transferred to London, the South Kensington Museum authorities agreed that their museum 'vans' could be used to transport the objects. They also agreed that the wall screens, which had been used to display the objects could be transferred as well. You can see an example here. [Précis of Board Minutes, Dept of Science and Art 1.1.1884 - 31.12.1887 page 29 July 24 1884 EM 6583] Find out more about the transfer here.

Again, no photographs of the Lane Fox displays at South Kensington Museum appear to have survived (if they were ever taken). The South Kensington Museum displays remained until 1884 when the slow process of transferring them to Oxford began. Eventually the authorities there had to close the displays before transfer began in order to clear the objects into one space so that an alternative use for Rooms L and K could begin. When the objects were actually transferred to London, the South Kensington Museum authorities agreed that their museum 'vans' could be used to transport the objects. They also agreed that the wall screens, which had been used to display the objects could be transferred as well. You can see an example here. [Précis of Board Minutes, Dept of Science and Art 1.1.1884 - 31.12.1887 page 29 July 24 1884 EM 6583] Find out more about the transfer here.

It has never been certain how many objects Pitt-Rivers also had in his home before 1884. A letter from H.N. Moseley to William Gamlen, Secretary to the University of Oxford, dated 8 February 1886 says:

... and I have also heard from General Pitt Rivers of numerous valuable sets of objects at his house in London and shortly to be received [at Oxford] ... Nothing is more difficult than to make absolute calculations as to the disposal of a collection of indefinite proportions which has never been arranged as a whole previously anywhere ...' [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/3]

Moseley means the sense of 'arrangement' when he says 'disposal'. For a short but detailed description of the founding collection prior to its transfer to Oxford we have to rely on the account given in 1883 to the Hebdomadal Council by the ‘Committee of Members of Convocation appointed to consider the offer by Major-General Pitt-Rivers ... of his Anthropological Collection to the University and advice them’ dated January 19 1883:

(i) A collection of prehistoric weapons and instruments, including a specially valuable series of Palaeolithic weapons from Acton. A fine series of Neolithic weapons from Denmark. A series of stone and bronze weapons from Ireland. A series of stone hammers. A series showing the gradual conversion of the simple bronze celt into the socketed form. Lastly, series of bronze hammers, of spear-heads and swords, and of implements of bone and ivory.

(ii) A collection of objects belonging to historic times.

A. Collection of weapons (of this a printed catalogue already exists) including—

(a) Defensive Armour :— Series of parrying sticks and shields from Australia, India and Polynesia. European shields of fifteenth century. Series of circular shields. Body armour from Polynesia, Japan, and China; Mogul scale and chain armour. Series of helmets, including bronze Greek and Etruscan helmets.

(b) Offensive weapons :— Series of boomerangs from Australia, India and North Africa. Throwing sticks. Bows. Cross-bows and quivers. Series of clubs, maces, and wooden battle-axes. Series of paddles, spears, javelins, and arrows. Series illustrating the development of the axe, halberd, glaive, and other cognate weapons. Several series illustrating the development and geographical distribution of various forms of swords, daggers, slings, lassoes, &c. A series of fire arms. A series showing the growth of the bayonet.

B. Collection of objects connected with domestic life, &c.

(a) Series illustrating modes of kindling fire :— Savage fire-sticks, flints, tinder-boxes, &c. Series of lamps (Babylonian, Roman, Egyptian, modern Algerian). Collections of mirrors, spoons, knives, &c.

(b) Valuable series of pottery and of bronze, silver, and glass vessels, illustrating especially the development of the various forms, and of the decorative patterns. This series comprises, besides a remarkably fine stand of Cypriote [sic] vases, Greco-Etruscan pottery, Samian ware, specimens from Mexico, Peru, India, Africa, Algeria, Japan &c; and also a collection of decorated gourds, and of basket-work.

(c) A collection of personal ornaments, necklaces, armlets, clasps, fibulae, &c, illustrating the development of particular forms. Especially valuable are the various series of gold and bronze ornaments (Cypriote [sic], Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Celtic, and Mexican).

(d) A collection showing the development of musical instruments (drums, stringed instruments, shell, horn, ivory, and bronze trumpets, &c.).

(e) A collection of objects of religious worship, and of charms, votive offerings, relics, divining-rods, &c. The series of votive offerings is very interesting. It ranges over a wide field, from ancient Cyprus to modern Brittany, and exhibits the most instructive coincidences of belief and ritual.

(f) A series illustrating the growth of the art of writing, including savage marks, Oghams, Runic inscriptions, &c.

(g) Series illustrating the realistic representation of human and animal forms (including some very fine terra cottas from Cyprus and Tanagra, Roman and Etruscan bronzes, Japanese masks of the sixteenth century, &c.). Series illustrating the conventionalised treatment of animal forms in decoration.

Series of mediæval panels illustrating the development of leaf-patterns out of architectural designs (to this the history of mural paintings at Pompeii offers an exact parallel, in the gradual transformation of the architectural designs into ornamental borders).

(h) A collection of harness, horse-shoes, spurs, and stirrups, ancient and modern.

(i) A series illustrating the history of boat and ship-building, comprising many beautifully-executed models of savage canoes.

... Oxford, January 1883.’

There does appear to have been slight differences in the types of objects displayed at Bethnal Green / South Kensington Museums and after the founding collection was transferred to Oxford. When the Hebdomadal Council considered the transfer in 1883 they received a report from Gilbert R. Redgrave, described as ‘an expert recommended by the Department of Science and Art at South Kensington’, which provided an estimate of dimensions of a building ‘suitable to a reception of the Collection’. He stated:

I understand that the agricultural implements and the wood carving from Brittany would not be needed, and about 100 sq. feet may be deducted on this account ...’ [Redgrave, ‘Approximate Estimate of the Museum-space required for the accommodation of the Pitt-Rivers [sic] collection’, Hebdomadal Council January 19 1883]

On 23 March 1883 Pitt-Rivers commented: 'I have just presented to the University of Oxford my museum which has cost me six thousand pounds at least ..' [L87 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Pitt-Rivers papers]

It is clear from the manuscript collections of Pitt-Rivers’ held at Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum that some items from South Kensington Museum were sent to Pitt-Rivers’ home after most of the objects were transferred to Oxford. A letter from Pitt Rivers’ solicitors confirms this:

‘You are aware that General Pitt Rivers has arranged to present the greater portion of his Anthropological Collection to the University of Oxford.’ [Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum PR ms collection, P132 Letter from Farrer and Co. to South Kensington Museum 24.5.1883]

In 1884 Pitt-Rivers confirmed the position:

I accordingly withdrew from my museum in London everything which related to agriculture and peasant handicraft, agricultural implements of various kinds, models of ploughs and country carts of different nations, household utensils, country pottery, cottage furniture, peasant costume, jewellery, and so forth, and put them into three rooms of a house near Farnham [Address to Dorset County Museum, page 13]

These items, in effect formed part of the collection later displayed at his private museum in Farnham, Dorset. There is no record of additional items being donated to Oxford than had been on loan to South Kensington Museum, though this might have been the case.

The University of Oxford had insisted the founding collection be donated rather than loaned which meant that Pitt-Rivers' involvement with his collection at Oxford formally ceased in 1884 when the University took over legal ownership. He may have intended to retain an active interest in the collection but in fact he visited the city only a few times after 1884, and gave only one formal lecture there in 1891—by which time the staff at the Museum had managed to get most of the founding collection artefacts installed and the museum open to the public. [Petch, 2007] In 1898 Pitt-Rivers complained to the then President of the Royal Anthropological Institute:

Oxford was not the place for [my collection] and I should never have given it there if I had not been ill at the time and anxious to find a resting place for [it] of some kind in the future. I have always regretted it, and my new museum at Farnham, Dorset represents my views on the subject much better. [Chapman, 1991:166 quoting from a letter PR to F.W. Rudler 23.5.1898 Salisbury and South Wilts Museum Pitt-Rivers Papers, Correspondence]

It is clear that because the University was slow to transfer the collections from South Kensington Museum, those museum authorities in the end lost patience and moved the collection into a storage area. Once the items had been transferred to Oxford they were moved to a variety of storage spaces whilst the University staff worked on creating the new displays for the Museum. Though South Kensington Museum had transferred many of the original display material it is clear that the collection became very confused, objects lost labels. Pitt-Rivers complains that the transfer took such a long time, and that the museum was not fully open until 1891, five years after transfer from London. Henry Balfour makes it clear that this was not his fault, he had to reconstruct series; label, catalogue, and arrange the series for the new museum. It is clear, therefore, that the displays Pitt-Rivers had arranged at Bethnal Green and South Kensington Museums were never duplicated in Oxford but that the displays in their new location were different, rearranged and augmented by new objects. [See correspondence from Pitt-Rivers and Balfour held in the PRM manuscript collections, and University Archives [University Archives, UC/FF/60/2/3] On 30 April 1891 Pitt-Rivers gave the only formal lecture he presented at the University of Oxford (the closest event that the Pitt Rivers Museum had to an opening ceremony) entitled 'The Original Collection of the Pitt-Rivers Museum: its principles of arrangement and history in the 'Museum Theatre' of the University Museum. [Oxford University Gazette XXI:414]

If you wish to find out more about the early history of the Pitt Rivers Museum and its founding collection please see the Bibliography at the end of this article.

This site will eventually provide detailed information about each of the items in the founding collection. Until this data is available you will find out information about these artefacts by going to the main museum database interface (objects and photographs)(manuscripts). If you search for 'Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers' in the 'Individuals associated with objects' field you will get access to all the relevant artefacts.

Find out more about the founding collection, see here.

Bibliography for this article:

Blackwood, B. 1970. ‘The Origin and Development of the Pitt-Rivers Museum’ in The Classification of Artefacts in the Pitt-Rivers Museum Oxford. Occasional Papers on Technology, II, Oxford: Pitt-Rivers Museum

Bowden, Mark. 1991. Pitt-Rivers - The life and archaeological work of Lt. General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers DCL FRS FSA. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Chapman, W.R. 1981. Ethnology in the Museum. Unpublished D. Phil thesis, vols I and II, Pitt-Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Gray, H. St.G. 1905. ‘A Memoir of Lt-General Pitt-Rivers’ in Excavations in Cranborne Chase vol V. Somerset [privately published]

Fox, A.H. Lane. 1875 [a] ‘On the principles of Classification adopted in the Arrangement of his Anthropological Collection …’ Journal of the Anthropological Institute4 (1875) 293-308

Fox, A.H. Lane. 1877 [b]. Catalogue of the Anthropological Collection lent by Colonel Lane Fox for exhibition in the Bethnal Green branch of the South Kensington Museum June 1874 Parts I and II. London: Science and Art Department of the Committee of Council on Education HMSO [Re-issued 1879]

Larson, Frances. 2007. 'Anthropology as Comparative Anatomy?: Reflecting on the study of material culture during the late 1800s and the late 1900s' Journal of Material Culture 2007: 12-89

Macgregor, A. 1997 'Collectors, Connoisseurs and Curators in the Victorian Age' in M. Caygill and J. Cherry (eds) A.W. Franks: Nineteenth Century collecting and the British Museum British Museum Press

Petch, Alison. 1998.‘‘Man as he was and Man as he is’: General Pitt-Rivers’ collections’ Journal of the History of Collections10 no. 1 (1998) pp. 75-85 Oxford University Press

Petch, Alison. 2002.‘Assembling and Arranging: Pitt-Rivers’ collections from 1850 to now’ in 'Collectors: Expressions of Self and Other Occasional Papers Series: Horniman Museum and Museu Antropologico of the University of Coimbra

Petch, Alison. 2006 'Chance and Certitude: Pitt-Rivers and his first collection' Journal of the History of Collecting 18 no. 2 pp. 57-266 Oxford University Press

Petch, Alison. 2007. 'Opening the Pitt Rivers Museum' Journal of Museum Ethnography 19 pp. 101-112

Pitt-Rivers, A.H.L.F. 1891. ‘Typological museums as exemplified by the Pitt-Rivers Museum at Oxford and his provincial museum at Farnham Dorset’ Journal of the Society of Arts, 1891:115-22

Thompson, M.W. 1977. General Pitt-Rivers: Evolution and Archaeology in the Nineteenth Century. Moonraker Press, Bradford-on-Avon UK

AP, 9 November 2009, checked September 2010 and updated December 2010, updated again in March 2011 when research made it clear that the PR displays in London were not reproduced at Oxford at all and again in April 2011 with the letter from Moseley to Gamlen. Updated again in May 2011 including adding additional information from the V&A;; revised February 2013 with new estimate for founding collection

Notes

[1] 22830 as at February 2013, this number is likely to increase over 2013 as the Excavating Pitt-Rivers project continues to find unentered items