It is known that Pitt-Rivers often used drawings or charts in his lectures to illustrate his text. However, he does not often list all the lecture aides he used so it is not clear, for all his talks, which charts and diagrams he pinned up on the walls for illustration. It is probable that often these drawings were then used, in a different form, as the plates to illustrate the published forms of his papers. Examples of such plates are shown here as illustrations.

The current whereabouts of the actual lecture aides is unknown and they could well have been destroyed in the intervening 110 years since his death. Presumably similar lecture aides used by Edward Burnett Tylor in his lectures at the University of Oxford, at around the same time, are held in the Pitt Rivers Museum's collections. Assuming that they did resemble those used by Pitt-Rivers then it can safely be said that the illustrations were quite large, often comprised of black-and-white or coloured-in line drawings and were done onto thick paper which was presumably pinned to the walls of the lecture theatre. In the case of Tylor's lecture aides, they were prepared by the Oxford University Museum assistant, Alfred Robinson, presumably under Tylor's instruction. To find out more about these lecture aides please consult the photographic collections on-line database, searching for 1944.1.25-103, each sheet is approximately 135 x 90 cms.

However, there is one talk which makes clear which lecture aides he used. At the end of the published version of his 1891 talk on Typological Museums, given to the Society of the Arts, there is a list of the 'diagrams illustrative of his collection'.Some of the descriptions sound similar to published diagrams and charts used as plates in other papers. It therefore seems probable that, at this late stage in his career, he was reusing old material to illustrate his talk. The notes at the end of each extract from the paper give the possibly linked plate:

At the conclusion of the paper General Pitt-Rivers exhibited and described a number of diagrams illustrative of his collection. The first was ones showing the evolution of the modern rifle and bullet through all its stages, some of which had entirely dropped out of public knowledge;[1] and in connection with this, he suggested the desirability of a similar series being arranged, before it was too late, of various electrical appliances, many links in which might easily be forgotten.[2]

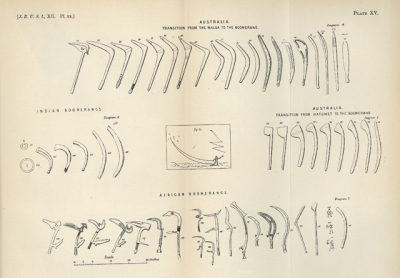

Next came a large diagram showing the arms of savages, which in the beginning were constructed of mere natural sticks and portions of branches, thus giving the form to the weapon which was sometimes imitated afterwards, when the art became more advanced.[3]

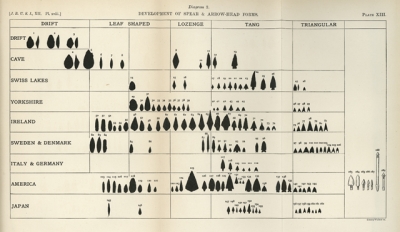

Flint implements came next, and arrow heads, the leaf-shaped being the earliest.[4]

Bronze and iron weapons were not always copied from wooden ones, though a similarity in shape might sometimes be traced; this was illustrated by a series of sword-forms. When metallurgy was first introduced, only small pieces could be cast, and therefore short daggers were the earliest forms of this class of weapon; the copper implements were of the simplest form, and the later iron ones more complex. One particular shape of sword was found over a large portion of Asia, being very similar to a Greek sword figured on vases, and it was probably derived from the Greeks.

Another series of diagrams was devoted to the development of ornament, and showing the changes which the loop, coil, and fret pattern had gone through; and another showed the cross, which, as a Christian symbol, was plainly derived from the Greek letters XP conjointly, which led naturally to the Celtic cross, still largely found in Scotland, whilst the Latin cross was a later form.

The degradation of silver coins, from the stater of Philip of Macedon was also shown. [5]

Another diagram illustrated how changes occurred through mistakes in copying, and were continued and increased until ultimately the original pattern was hardly recognisable. This was especially the case in representations of the human countenance, and had, in the opinion of Gen. Pitt-Rivers, led Dr Schliemann into an erroneous belief that the figures found on certain vessels at Hissarlik were Trojan remains, as bearing the image of the owl-faced goddess, Glaukopsis Athene, whereas, in truth , there was nothing of the owl-face about them, but merely the degraded and conventionalised type of the human face.[6]

Note that the above is given in one paragraph in the original version published on page 120-121 of the paper; it has been broken up into separate paragraphs for ease of reading.

The full list of plates from his major publications on ethnographic objects or his founding collection is given here.

Notes:

[1] These might be the illustration (unnumbered) used in ‘The Improvement of the Rifle as a Weapon for General Use’ from the Journal of the United Services Institution.

[2] One of Pitt-Rivers' sons was very interested in the development of electrical appliances, see biography for further information.

[3] Possibly Plate III of Evolution of Culture which shows clubs, spears, shields and boomerangs

[4] There are a number of options that might match this, but probably Plate XVIII from Primitive Warfare II is the closest.

[5] Plate VII [sic]or XII [sic] of Evolution of Culture (1906). Note that this plate does not appear to be discussed in the paper itself, which says clearly that the final plate is the discussed in Note 6 below. Find out more about this illustration here.

[6] This is Plate V of 'Evolution of Culture' (1875), which is titled 'Realistic Degeneration illustrated by representations of the human face, found by Dr Schliemann at Troy', it is discussed at length at the end of 'On the Evolution of Culture' (1906, p. 42-3):

My next and last illustration is taken from the relics of Troy, recently brought to light by Dr Schliemann. In the valuable work lately published by him he gives illustrations of a number of earthenware vases and other objects, called by him idols ... which he believes to represent Athena ... I shall in no way weaken the evidence in favour of Dr Schliemann's discovery of the true site of Troy if I succeed in proving that, according to the true principle of realistic degeneration, this figure does not represent an owl but a human face.

The figures on Plate V are all taken from Dr Schliemann's representations ... The two first figures, it will be seen, are clearly intended to represent a human face, all the features being preserved. In the two next figures, the mouth has disappeared, but the fact of the principal feature being still a nose and not a beak, is shown by the breadth of the base and also be the representation of the breasts. In the two succeeding figures the nose is narrowed at the base, which gives the appearance of a beak, but the fact of its being still a human form is shown by the breasts. Had the idea of an owl been developed through realistic degeneration of these two last figures, it would have retained this form, but in the two succeeding figures it will be seen that the nose goes on diminishing. In the remaining figures ... this degeneration of form is the result of haste.

What then are these solid stone objects? I cannot for a moment doubt .... that they are votive urns of some kind ...

AP, February 2011.