To search the RPR site click here

Pitt Rivers inherited King John's House with the rest of his estate from Lord Rivers. Some ten years after receiving his inheritance he privately published a pamphlet about the restorations he had made to the house and the objects workmen had found during the work. These objects were not listed in the catalogue of the second collection but they were obviously kept as at least part of this collection is now found in Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum collection.

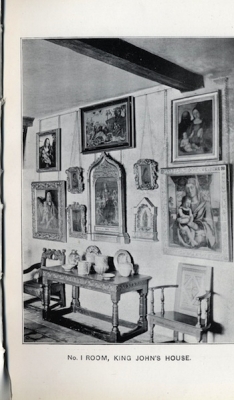

Pitt-Rivers wanted his art collection to show the progression of art through history, 'a series of small and for the most part original pictures, illustrating the history of painting from the earliest times' as he said himself. He took a strict approach, mixing schools and countries' art as appropriate.

The chronological approach followed the German model as put forward by Gustav Waagen in Berlin for the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in the 1830s and 1840s, and was also the way that the Louvre in Paris was hung (with greater emphasis on chronology than stylistic format). Pitt-Rivers may even have been to see this model on one of his many holidays in Germany (though he seems mostly to have visited southern Germany) or France. As Yallop remarks:

Waagen's displays ... presented objects within their chronological and social contexts, supported by explanatory labels and catalogues. This allowed visitors to get a sense of how one artist's work related to another's, and how practice had evolved across time and in different places. Waagen also advocated re-creating a sense of the original spaces in which the works of art would have been displayed 'to lessen as much as possible the contrast which must necessarily exist between works of Art in their original site, and in their position in a museum ...' [2011: 117]

Judging by the second illustration on this page, Pitt-Rivers too sought to make his pictures at home in their environment at King John's House, and was seeking the same forms of enlightenment in his visitors as Waagen.

The alternative model put forward in Victorian England was to collect and display important works of differing styles in style groups, this became a common art gallery style of the twentieth century, as art history became increasingly concerned with 'schools' or stylistic modes, like impressionism, or expressionism.

Ruskin was a supporter of the highly organized art gallery display saying 'Nothing has so much retarded the advance of art as our miserable habit of mixing the works of every master and every century ... Few minds are strong enough first to abstract and then to generalise the characters of paintings hung at random'. [quoted in Yallop, 2011: 56-7] In other words order was essential if displays of art work were primarily for didactic purposes. This was fully recognized at the time, The Times of 15 May 1857 described the arrangement of the Manchester exhibition of that year as allowing 'the eye to take in at a glance the broad distinguishing characteristics of successive periods and schools of art'. [quoted in Perham, 2011: 62] Pitt-Rivers' strong urge to educate via museum display, and his undoubted intention to use King John's House as an art education tool were following on strong historical precedents.

Pitt-Rivers published a short guide to the Larmer Grounds, King John's House and the museum at Farnham for the use of readers. Here is what he said about King John's House:

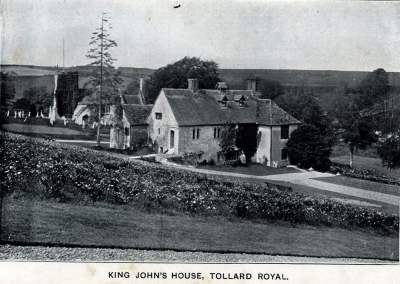

King John's House, Tollard Royal

King John's House at Tollard Royal is a building of the 13th Century, of which period two characteristic windows with stone seats in them have lately been discovered in the walls. The 13th Century house was of oblong shape, and may be distinguished by the thickness of the walls. The rest of the house is of the Tudor period, and the three oak-panelled rooms are of that date. It contains a series of small and for the most part original pictures, illustrating the history of painting from the earliest times, commencing with Egyptian painting of mummy heads of the 20th and 26th Dynasties, B.C. 1200-528 and one of the 1st Century, A.D. The transition from the round to the flat in the painting is shown by three Graeco-Egyptian mummy paintings of the 2nd or 3rd Century, one of them admirably executed, obtained by Mr Flinders Petrie in Egypt, and an early Greek wall painting.

Passing on to the decline and conventionalization of art in the Middle Ages, the earliest European picture is one of the "Virgin and Child," by Margaritone, of Arezzo in Italy, born 1216, died 1293, and signed by him; followed by several Greek and Byzantine conventional paintings in the same style, which continued in connection with the Greek and Russian Churches until a much later period. The series is continued in the order of dates by S. Memmi, School of Siena , A.D. 1283, and a door of a triptych of the early Italian school. The 15th Century is represented by Giovanni Bellini, Venetian School, signed by him, 1427-1516; "The Holy Family," by Palmezzano, Italian, 1456-1537; "The Virgin and St John," School of Suabia, circa 1460; "The Woman taken in Adultery," on the stair-case by Lucas Cranach, 1472-1553; "The Torments of Hell," over the chimney-piece downstairs, and another of a similar subject by H. Van Aeken, commonly called Jerome Bosch, 1460-1518. Pictures of this kind were much used in those days to frighten people into repentance. Another by the same painter is upstairs, representing the "Dream of St Anthony," and another representing "Orpheus and the Beasts." On the staircase, "A Banker and his Wife," by Quintin Matsys, Flemish, 1466-1531. On the staircase, "The Prodigal Son," by the same painter; "A Lady in the School of Holbein," in the upper room, 1493-1554, and another of the same date in the adjoining room; a "Virgin and Child," of the Italian School; "Modesty and Vanity," by Luini, Italian, 1460-1530; "The Resurrection and Judgment," Italian School, circa 1480. At the foot of the stairs, 'The Crucifixion," by Hans Shaenflein, 1487; "Jesus in the Garden," and another by Hans Burgkmair, 1474-1559. The 16th Century is represented by a "Virgin and Child," School of Sienna, 1500; one by Roselli, School of Florence, 1578-1651; "Paying Tithes," by P. Brueghel the elder, 1530-69; "A Martyrdom," German School circa 1500; a "Descent into Hell," and an "Ascent into Heaven." by Frans Floris, 1517-70; "The Miracle of the Slave" by Tintoretto, 1512-94 (this is believed to be the small picture painted by him in preparation for the large picture at Venice); "The Sacking of a Dutch village," by Alsloot, end of the 16th century. The pictures of the 17th Century include: "A Village Festival," Dutch, by Peter Van Bloemen, 1657-1719; a "Virgin and Child," by C.B. Salvi, called Il Sassiferrato, Italian, 1605-85; "A Skirmish," by Palamedes Stevaerts, 1607-38; "A Dog catching a Heron," by Abraham Hondius, Dutch, 1638-95; a Dutch picture of horses, after Cuyp, 1605-91; "Peasants," by Dirck Stoop, 1610-86; "A Canal Scene in Winter," Dutch, by Van der Heyden, 1637-1712; "The Journey to Emmaus," Italian, style of Gaspard Poussin, 1613-75; "Vandyke when young," by Peter Tyssens, 1616-83; "A Village Festival," Dutch, by Thomas Van Kessel, 1677-1741. The 18th Century is represented by "A Fish Saleswoman," by G. Morland, English, 1763-1805; two pictures of Hudibras, unknown; "the Repulse of the Dutch at Tilbury in 1667," by A. Ragon. The pictures of the 19th Century include: "The Siege of Pamplona in 1813," by G.C. Morley, 1849; "A Coast Scene," by T.B. Hardy; "Fish, and a Copper Vessel," by Cammile [sic] Muller, 1880. These pictures are hung as much as possible in the order of dates, but the rooms do not admit of the historical arrangement being strictly adhered to.

In the different rooms are also exhibited specimens of various kinds of modern ornamental pottery, in imitation of the mediaeval and early wares, including Martin stone-ware, De Morgan lustre ware, Hispano-Moresque ware, Aller Vale ware, Doulton ware, and modern Nevers ware. Specimens of Tudor embroidery and needlework are exhibited in the upper rooms.

... An illustrated description of King John's House, by General Rivers, is kept on a desk in the lower room. In one of the upper rooms are relics found in the house during the excavations carried on, in, and about it, including a coin of King John, and other objects of the same period. One of the rooms is used as a reading room by the villagers in the winter months.

Luncheon and other refreshments can be obtained at King John's House on applying to the Caretaker, whose charges are very moderate. It is within ten minutes' walk of the Larmer, over park-like grounds from which beautiful views across the Park and distance are obtained.

The house is described by Pitt-Rivers first biographer, Michael Thompson, as:

'The name [King John's House] was applied to a building later than John's reign and, as we have seen, is a transference from the Manor House at Cranborne. The house lies to the south-east of the parish Church, and consists basically of a first-floor hall oriented east/ west, with traces of a contemporary latrine tower at the south-west end and a seventeenth century cross range on the east end. Most of the thirteenth century two-light windows were exposed and partly restored by Pitt-Rivers in 1889, when he carried out much work on the structure and excavated the adjoining area. The exhibition of the house was intended to illustrate the history of painting and pottery-making. This valuable collection, containing paintings by Giovanni Bellini, Tintoretto and others, was the fine arts section of the main collection housed at Farnham.' [Thompson, 1977: 85]

Note that the artistic attributions have in many instances been changed, the Bellini (for example) is now thought to be by Bastiani. Pitt-Rivers' second biographer, Mark Bowden, says:

'King John's House near Tollard Royal church was by tradition a medieval hunting lodge frequented by King John, but in the late nineteenth century there was nothing in its outward appearance to suggest that it was really any earlier than the sixteenth century. In 1889 the House fell vacant and Pitt Rivers seized the opportunity 'to examine the walls, and see if anything could be found to confirm the tradition of its great antiquity'. ... A memorandum in one of Tomkin's notebooks (PRO WORK 39/ 10) suggests that the General considered rebuilding this tower but he abandoned the scheme and, having repointed the foundations of the tower, he turned his attention to the roof of the House and examined the loft ... The General was as rigorous in recording his restoration work here as he was in recording his archaeological excavations. ... The General's thorough recording of architectural details at King John's House has recently been held up as an example for investigators of historic buildings ...' [Bowden, 1991: 123]

Bowden identifies the political diatribe at the end of the book (quoted below) as referring to the Ground Game act recently introduced by the Liberal government which 'was intended to allow tenant farmers to protect their crops against injury from hares and rabbits'. [Bowden, 1991: 126] About the 'supplementary museum' use of King John's House, Bowden remarks:

'The collection on display included works by Giovanni Bellini [see above], Lucas Cranach, P. Brueghel the elder, Tintoretto, Durck Stoop, Peter Tyssens and George Morland, hung as far as possible in chronological order and augmented by examples of embroidery and needlework (le Schonix 1894, 170). The finds from the excavations were also displayed in the House with modern reproductions of medieval pots.' [Bowden, 1991: 144]

Bowden concludes:

'Pitt Rivers' work at King John's House is remarkable for the detailed architectural recording, the carefully thought out restoration policy for the fabric of the building itself and for the deliberate attempt to use the episode for the purpose of putting the study of medieval antiquities on a sounder basis.' [Bowden, 1991: 126]

According to British History Online,

'King John's House was presumably the manor house of either Tollard Govis or Tollard Lucy. The stone central block of the present house was in the mid 13th century a cross wing, north of which stood the hall. The wing was of two storeys, perhaps with one room on each floor; a garderobe chamber projected from its south-west corner. Several medieval windows survive; those on the ground floor are small double-splayed lancets, most of those on the upper floor have two lights and internal seats. In the 17th century a chimney stack was inserted, dividing each floor into two rooms, a large timberframed cross wing was added at the eastern end, and a stair turret, perhaps replacing a stair which had been in the hall, was built on the north side. Under the direction of A. H. L.-F. Pitt-Rivers the house was extensively restored in the 1880s, some early 19th-century additions were removed, and a singlestorey extension was built north and north-west of the medieval block. After 1966 a pagoda, of two storeys, was built in the garden. ... In 1889 or 1890 King John's House, formerly a farmhouse, was opened to the public by Pitt-Rivers. It housed an exhibition illustrating the history of painting and displays of pottery and needlework. A room in the house was used as a reading room for residents of Tollard Royal. The house was still open in 1905 but by 1907 had become a private residence.'

Following section taken from King John's House, Tollard Royal, Wilts by A.H.L.F. Pitt-Rivers, 1890 (printed privately)

'The House which forms the subject of this paper has always been known traditionally as King John's House, and is situated close to the church of Tollard Royal in Wiltshire. Whether or there are grounds for believing it to have ever been an actual possession of King John's, it seems desirable to speak of it by the name that is generally known by in the neighbourhood. ... There are ancient terraces in the vicinity of the House which have been thought to denote the existence of more extensive premises in past times; ... but it seems more probable the terraces were for [the purpose of vineyards]. ...

The House itself had little of interest in its external appearance at the time I first saw it. An illustration of its north front and of the staircase, and the fireplace ... is given in the "Gentleman's Magazine," dated September, 1811, which has also a brief description of it. ... Little change appears to have taken place since then, on this front of the House. The window ... which was then open, has since been closed up, and the wall stuccoed over it. The other window on this side, in the angle of the House over the staircase ... was then closed, as it was when I first saw it. It was only discovered afterwards by peeling off the stucco.

The appearance of the south side of the House, before the exploration of it began, is shown in the drawing (Plate V) except that the thirteenth century window ... is shown in the drawing, but was not discovered until afterwards. ... At the west end of the House, the Elizabethan window, ... was also closed up. ...

I decided that any restoration that I might make, the work of both periods should be preserved, only removing that of the later period, where it completely hid the earlier work; but that the quite modern additions, some of which had been done by Lord Rivers not more than 40 or 50 years ago, and which were of very inferior workmanship, and thoroughly utilitarian design, should be entirely removed.

The inside had been altered from time to time for the convenience of the inmates, in accordance with modern ideas of comfort and, like most work done at that time, with entire disregard of all antiquarian interests.

[Pitt-Rivers continues to systematically describe the rooms of the house, what he found when he first saw it and what he discovered and renovated, below is a short sample to give a flavour of the work he did]

... The oak panelling of the Elizabethan room No 2 was in good preservation, but painted white. I had the paint removed. .... The fireplace ... had been closed up, and a modern grate inserted, which I removed. ... An opening ... was discovered in the old wall, the purpose of which I have never ascertained. This has been left. ... The sides of the old fireplace had been formed into cupboards on both sides of the modern fireplace, and it was only by examining the backs of these cupboards that the existence of the large old fireplace was discovered. This was opened out. The curiously shaped porch to door No. 1 is modern, but it is represented in the "Gentleman's Magazine" drawing of 1811. The Elizabethan window, ... with five mullions, remains as it was found. In peeling the stucco from the walls ... the thirteenth century window was discovered, no trace of which could be seen inside or out, previously to the examination of the walls. ...

The oak staircase is a good specimen of Elizabethan work, and is in good preservation. ... It is the same that is represented in the "Gentleman's Magazine" illustration. ... . Window No. XVII was a modern sash window put in by the 4th Lord Rivers, the original one having been removed. I should have had some difficulty in restoring this, had not the adjoining Elizabethan window, No XVIII, been found blocked up in the wall. Both are now of their original form and dimensions. The opening x between this room and numbers 12 and 13 was originally a thirteenth century window, a pointed arch having been discovered above it, and the sides splay out towards the inside, like the other windows of that period. It was turned into a doorway in Tudan times. The walls of room 12 are of timber work and plaster, but it has a good oak chimney piece, of the Tudor period ...

Passing now to room 10, the loop-hole No XIV, was discovered in the west wall. No trace of it was seen on the surface, which also applies to the door No 12 leading into the tower. ... Both of these are covered up on the outside by the lean-to shed ... In the loop-hole the original oak shutter was found on its hinges, plastered up in the wall. It was unfortunately lost by the workman to whom it was entrusted for safe keeping, but another has been made exactly like it and attached to the old hinges. It consists of a plain piece of oak, without panelling. There is no sign of this loop-hole having ever been glazed, and the same applies to the thirteenth century window afterwards discovered. The door No 12 had evidently opened outwards, and this led me to conjecture that there must have been a tower at this angle of the building. On peeling the walls outside the alternate bonding stones of the tower were seen running up the wall as shown in the elevations, ... and this caused me to excavate the ground beneath, which resulted in the discovery of the foundations of the tower ... with walls 3 feet thick, in good preservation. The tower was of flint rubble, with sandstone quoins, like the House itself. ... The foundations of the tower have since been pointed and preserved.

Above the room 10 was a loft in the roof ... It had been boarded up, but having had the rafters removed, I crept into it to examine the top of the wall, when to my surprise and delight, I found the tops of two pointed arches, just showing above the floor of the loft ... It was evident now that this had originally been an early window of larger size ... Only a few minutes after this discovery sufficed to remove the all the Tudor work from the window, and it was then found that there were stone seats in the wall on each side, of the form well known to be of the thirteenth century. ... The stucco was then peeled from the wall, above the Tudor soffit on the outside, and the arches of double lights were found built up in it ... This discovery showed me that my search had been rewarded, and that we had now found work nearly approaching if not actually dating back to the time of King John. Competent architects, who have seen the window, pronounce it to be early thirteenth century. ... Careful models have been made of both windows, showing their exact condition at the time they were found, and the position of each stone and brick is given by means of which architects and antiquaries will be able to see clearly what has been done, and what authority exists for the slight restorations that have been made.

Relics found in and about King John's House

During the explorations which were made inside the House, and the excavations in search of the foundations outside, relics and fragments of various kinds turned up and have been preserved. It has not hitherto been customary, in archaeological publications, to give drawings of objects found during the repairs of mediaeval buildings, and I can understand that the importance of illustrating common objects, such as those included in the seven plates attached to this memoir, may not at first sight strike every archaeologist. It is true that mediaeval relics have not the same importance as those of pre-historic times, in which they generally afford the only reliable evidence of time. In dealing with historic buildings, they are only accessory to the main object of our researches. Nevertheless, there are conditions in which they afford the only evidence available even in mediaeval times, and a more thorough knowledge of them than we possess would be desirable. Earthworks, entrenchments, and the foundations of buildings have rarely any data attached to them, and the architecture is not always in itself sufficient to determine the date. We now know more about the kinds of tools and other common objects used by the successive races of pre-historic men, than we do of those of our more recent ancestors. In our Museums a department of mediaeval antiquities is by no means common. ... In fact the subject has not been much studied, and it is with hope of promoting this branch of enquiry that I have had so many little objects figured, that have been found in this House, to some of which I am unable to assign any date. The House having been occupied continuously for six or seven centuries, relics of different periods have been found huddled together, and there were no deposits by mean of which one period could be distinguished from another, except in so far that the things found buried in the foundations of the tower, and the things silted over at the foot of the west wall of the House ... must be of the earliest period of its occupation.

Pottery

Although no entire vessels were found in the House, many characteristic fragments were discovered ... These I have identified as far as possible by specimens in the Guildhall Museum, in my own museum, and elsewhere. ....

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the fragments found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection. However, they were obviously kept as at least part of this collection is now found in Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum collection

Clay tobacco pipes

The date of clay tobacco pipes may be known by their form, size and the stamps upon them. ...

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the pipes found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

Knives and forks

... It is not customary in the old days to provide knives and forks for guests. Throughout the sixteenth century everyone carried his own knife about with him ... To this day the Highlanders, when in full costume, carry the Skein-Dhu or knife in the garter or in the sheath of the dirk. ... In the East it is still the fashion to eat with the fingers. Not long ago, when dining with a Pasha in Egypt, I was rather startled by his taking up a piece of meat from his plate with his fingers and putting it into my mouth. It would not have been thought polite to have refused to comply with this custom, which is considered to be a compliment.

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the knives and forks found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

Spoons

Spoons were in use before forks. The same form of spoon continued in use in England from the middle of the fifteenth century to the time of the Restoration. ...

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the spoons found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

Spurs

Two spurs were found in the Tower.

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the spurs found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

Shoes of horses and oxen

Two specimens of horseshoes found in the ground near the house are those of small animals. Shoes of oxen were found in considerable number in an outbuilding ...

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the shoes found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection. However a horse shoe is recorded as being found at the house in the catalogue: Add.9455vol3_p1002 /3 'Celtic Iron Horse shoe found in the Garden of King John’s House Tollard Royal (Does not correspond with shoe found by Mr Johnson)', see catalogue for illustration. This item was found in May 1894, four years after the book was published]

Bridle bits

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the bridles found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

Purses

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the purses found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection]

English arrow-heads

English arrow-heads are of extreme rarity, and I am not aware of the existence of any other collection of them found in connection with an ancient building. ...

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the arrows found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection. However, two arrowheads were found in 1894 and listed in the second collection: Add.9455vol3_p1005 /2-4: Bronze fibula and two iron arrow-heads Found in the garden of King John’s House]

Locks and keys

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the purses found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection. However, they were obviously kept as at least part of this collection is now found in Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum collection]

Buckles

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the buckles found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection.]

Ring Brooches

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the brooches found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection. However, a fibula was found in 1894 and listed in the second collection: Add.9455vol3_p1005 /2-4: Bronze fibula and two iron arrow-heads Found in the garden of King John’s House]

Coins

A few coins were found in and about the House, serving to define with greater certainty than other objects, the time at which they must have been in use by the inhabitants.

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the coins found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection.]

Animal Remains

In the refuse pit in the tower, and in the foundations of outbuildings to the west of the House, numerous bones were found, some of which, being entire, afford data for the estimation of size, and all of which, from the position in which they were found, are probably from the earliest period of the House.

[there follows a description and attribution by Pitt-Rivers of the animal remains found, none of which are entered in the Cambridge University Library catalogue of the second collection.]

The ground was afterwards excavated on the slope of the hill to the west of the House, which led to the discovery of outbuildings ... These consisted of an oven and fireplace, where it is probable the cooking for the House may have been done. The foundations of oblong buildings were also found, which from the number of shoes of oxen found in them, appear probably to have been cow-sheds. ... These ruins have now been covered up again. ...

The probability is that King John's House resembled, on a small scale, the Castle at Acton Burnell in Shropshire ...

The windows in King John's House do not appear to have been glazed, but were closed with shutters, the hooks for the hinges of which were found, and have been used to hang new shutters upon. The form of the shutters conformed to the pointed arches of the double lights ... When shut the interior must have been left in darkness. ...

From the foregoing remarks it will be seen that there is a concurrence of evidence in favour of a very early origin for the House. The windows and several features of the architecture are undoubtedly thirteenth century; some of the fragments of pottery are Early English; the buckle ... and, above all, the coins of the early period of King Henry III ... speak of the same date. There is nothing to indicate a palace, but it must have been a house of fair size for the time, consisting of a basement and upper floor, each containing one room, the basement 38 feet by 167 feet, the upper floor 40 feet by 18 feet. ... The well was probably in its present position to the east of the House. I have not been able to ascertain the position of any fireplace in the old building, and it seems not unlikely that the fire may have been kindled on a hearth in the centre of the upper room, the smoking finding an exit in a hole in the roof. The roof was probably a pent-roof such as it now is. The walls were 4 feet thick on the basement and 3 feet on the upper floor. Such as it was, and situated in the heart of the Chase, it might very well have formed a lodgment in those days for hunting purposes, even for a king. The seats at the window show that it was a permanent residence of some kind, and if King John ever did reside upon the knight's fee in Tollard, as tradition affirms, it must have been here he lodged. There can be little doubt that it must in some way have been connected with the Chase, as a place where the Swainmote was held, or as a residence for the Trustees of the Forest ... Having apparently been occupied continuously ever since, it must have seen many vicissitudes in the Forest ... It may have seen torture or death inflicted for hunting in the Royal Domains, and the penalty of trespass visited upon the sons and heirs of the offenders. ... Later on it saw the final abolition of the Chase by Lord Rivers in 1830, and lastly, after six or seven centuries of continually increasing freedom and respect for the rights of private property, it has again witnessed a relapse in our idea of liberty. It has seen existing contracts broken into and tyrannical measures again introduced - not this time in the interests of kings or nobles, or agricultursts, or of the people, but of demagogues and political agitators. It has seen the ground game - the private property of the landowners - arbitarily confiscated and given to others in exchange, as it is vainly hoped by these robbers, for parliamentary votes for themselves - a measure not perhaps of very great importance in itself, and one which I myself, as an owner of property, am inclined to view with great com placency; but potent for evil as a precedent for further confiscation and robbery, that is intended to follow it if those by whom it was instigated have their way to the end.

In its final stage, after completing the necessary repairs to it, I have furnished it with old oak chairs and ta bles mostly of the seventeenth century, and turned it into a supplementary Museum to my collection at Farnham. The basement room No 2 is at present used as a reading and recreation room for the villagers, and the remainder of the House is occupied by a small collection of original pictures, illustrating the history of Pain ting, from the earliest Egyptian times to the present, with other objects of art in cases in several rooms. It is generally open to the public, and is much visited by people from the neighbourhood.

[Plates of illustrations, mostly described as 'ink-photo Sprague & Co London', conclude the volume. They look like drawings.]

To find out more about the items displayed at King John's House from the second collection go here.

Bibliography for this article

Bowden, Mark 1991. Pitt Rivers: The Life and Archaeological Work of Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Caverhill, Austen (no date) Rushmore Then and Now: A short history of Rushmore House and Park, at one time residence of Lieut-General A.H. Pitt-Rivers and now the home of Sandroyd School No publisher [published on the occasion of Sandroyd's Hundredth anniversary]

Pergam, Elizabeth A. 2011. The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857: Entrepreneurs, Conoisseurs and the Public Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate

Pitt-Rivers, A.H.L.F. 1890 King John's House, Tollard Royal, Wilts. Printed privately

Pitt-Rivers, M.A. 1995. A Short Guide to the Larmer Grounds Rushmore. [Privately printed]

le Schonix, R. 1894. 'The Museums at Farnham, Dorset, and at King John's House, Tollard Royal', The Antiquary 30, 166-71

Thompson, M.W. 1977. General Pitt Rivers: Evolution and Archaeology in the Nineteenth Century Bradford-on-Avon: Moonraker Press.

Yallop, Jacqueline. 2011. Magpies, Squirrels & Thieves: How the Victorians collected the world London: Atlantic Books

[Above excerpts transcribed by AP June 2010 and March 2011 for the Rethinking Pitt-Rivers project, information added August 2011]