ENGLAND: THE OTHER WITHIN

Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Funeral food

Alison Petch,

Researcher 'The Other Within' project

In most parts of England, after the funeral, people who had attended would be provided with some food and drink by the surviving relatives. It was also the custom, in the north of England, to provide biscuits for the mourners, people attending the house during the period immediately following the death and funeral, to take away. [see Roberts, 1989: 201 and other sources listed in the bibliography]

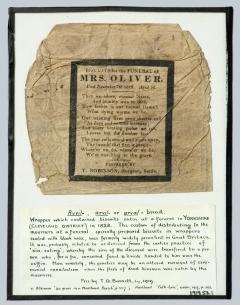

One of the more unusual objects in the Pitt Rivers Museum is described in the accession book as

'Paper wrapper used to contain biscuits given to a mourner at the funeral of Mrs Oliver, 7 Nov., 1828. Cleveland district, Yorkshire. Biscuits of special make were distributed to mourners, wrapped in paper envelopes sealed with black wax, at a recognized stage in the ceremony, together with wine. The biscuits were round & resembled sponge-cake. Female "servers" distributed the biscuits & wine & when the funeral procession was marshalled, walked immediately in front of the coffin. Formerly the "biscuits" were called Avril, arvil or arval bread (Arval = "succession ale" = inheritance feast among the Norsemen)'

This object is on display in the Court (ground floor) of the Museum, in Case 122.A - Treatment of the Dead.

As can be seen in the picture, the wrapper states:

Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828. Aged 52

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

Our waisting [sic, particularly unfortunate as it wraps a biscuit] lives grow shorter still

As days and months increase;

And every beating pulse we tell

Leaves but the number less

The year roll round and steals away,

The breath that first it gave;

Whate'er we do, where'er we be,

We're travelling to the grave.

Prepared by T. Robinson, Surgeon, Settle.

The old museum label says:

Avril-, arvil- or arval- bread

Wrapper which contained biscuits eaten at a funeral in Yorkshire (Cleveland district) in 1828. The custom of distributing to the mourners at a funeral specially prepared biscuits in wrappers sealed with black wax, was formerly widely prevalent in Great Britain. It was, probably, related to or derived from the earlier practice of "sin-eating", whereby the sins of the deceased were transfered [sic] to a person who, for a fee, consumed food & drink handed to him over the coffin. More remotely, the practice may be an altered survival of ceremonial cannibalism when the flesh of dead kinsmen was eaten by the mourners. Pres[ented] by T.G. Barnett, Esq., 1919 v. Atkinson "40 years in a Moorland Parish" p 227, Hartland "Folk-Lore" XXVIII 1917, p 303

The poem is the first three verses of a Methodist hymn, written by Charles Wesley, and titled 'Worthington'. Charles Wesley (1707-1788) was a Methodist leader, the younger brother of John Wesley. The full version of the hymn is:

WORTHINGTON By Charles Wesley

THEE we adore, eternal name!

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame,

What dying worms we be!

Our wasting lives grow shorter still,

As days and months increase;

And every beating pulse we tell

Leaves but the number less.

The year roll round, and steals away

The breath that first it gave;

Whate'er we do, where'er we be,

We are travelling to the grave.

Dangers stand thick through all the ground,

To push us to the tomb;

And fierce diseases wait around,

To hurry mortals home.Great God! on what a slender thread

Hang everlasting things;

The eternal states of all the dead

Upon life's feeble strings!

Infinite joy, or endless woe,

Depends on every breath;

And yet how unconcerned we go

Upon the brink of death!Waken, O Lord, our drowsy sense,

To walk this dangerous road!

And if our souls be hurried hence,

May they be found with God![Version given at http://www.iment.com/maida/familytree/henry/music/p45.htm, note that there are tiny differences with the biscuit wrapper version, however, other internet versions confirm this version rather than the wrapper's]

It is to be presumed that the mourners would have been expected to recognize the words, and to know the entire hymn.

Thomas Barnett, the donor, was a Birmingham jeweller and goldsmith and amateur antiquarian and archaeologist. Nothing more is known of Mrs Oliver or T. Robinson. It is not known how Mr Barnett obtained the wrapper.

This object was published by Edwin Sydney Hartland (1848-1927), solicitor and keen folklorist, in Folklore , in 1917 and discussed at the meeting of the Oxford University Anthropological Society on 1 November 1917. Interestingly, in his paper, Hartland does not transliterate the hymn accurately, replacing the word 'own' with 'bow'. According to Hartland this was:

'... one of the very few material relics of a custom once prevalent in Yorkshire and elsewhere of handing each mourner at a funeral a packet of cake or biscuit.'

Hartland provides various examples of the types of cakes used for this purpose. He describes them as 'avril bread' (which appears to be incorrect). He suggests (with little evidence to support his theory) that 'the custom of providing cakes or biscuits at a funeral is not remotely related to that known in Wales and the Marches as Sin-eating .' [NB this phrasing is somewhat ambiguous to modern readers, he means that it is closely related to sin-eating, as is clear from the journal]. Sin-eating was the practice of eating some food or drinking some wine during or before the funeral, 'by doing so he was held to take upon him all the sins of the deceased and thus free the latter from unrest and the disturbance of the survivors.' [Hartland, 1917: 308]

Another member of the Folk-lore Society, T.W. Thompson from Sheffield, replied in Folklore in 1918 that his mother, from the Lake District, had also remembered Arval bread, which was handed round for every person who was to be asked to the funeral. The bread was taken home and not consumed at the funeral. Arval appears to be the correct term for this bread as OED describes arvel (also spelt arvel and arvill) as 'a funeral feast', and cites several early examples:

'1691 RAY N. Countr. Words 139 Arvel-Bread, Silicernium. 1778-80 W. HUTCHINSON Northbld. II. 20 in Brand's Pop. Antiq. (Hazl.) II. 193 On the decease of any person possessed of valuable effects, the friends and neighbours of the Family are invited to dinner on the Day of Interment, which is called the Arthel or Arvel-dinner. 1807 DOUCE Illust. Shaks. II. 203 (Jam.) In the North this feast is called an arval or arvil-supper; and the loaves that are sometimes distributed among the poor, arval-bread. 1875 Whitby Gloss., Averill-bread, funeral loaves, spiced with cinnamon, nutmeg, sugar, and raisins.' [ED online link]

Bertram Puckle is his overview of funeral customs, still much quoted today, states:

'An interesting survival is mentioned in Howlett, who states that, "in Cumberland, the mourners are each presented with a piece of rich cake, wrapped in white paper and sealed, a ceremony which takes place before the 'lifting of the corpse,' when each visitor selects his packet and carries it home with him unopened, and in some parts of Yorkshire, a paper bagof biscuits, together with a card bearing the name of the deceased, is sent to the friends." [England Howlett F.S.A. "Burial Customs" (Curious church customs and cognate subjects) Edited by Wm. Andrews] In this we clearly trace the custom alluded to, of obtaining prayers in exchange for material consideration, whilst the more substantial gift of a flagon of ale and a cake given to the officiating minister in the church porch ... would be considered as partly in payment for services rendered and probably also for the merit of his special prayers.' [Puckle, 1926: 109]

Carrick, in 1929, describes how in Cumbria, on the day of the funeral small loaves of bread were distributed as "arval breed". This was a survival of the arval dinner or feast provided by the heirs for all who attended the funeral. According to the author this was later replaced by the funeral tea.

Roberts, discussing death in Lancashire from 1890-1940, also describes the biscuits:

'The tea was always at home. When you went to the funeral you always got a funeral biscuit wrapped in paper. It was like a sponge. I know a little girl died. Our Tom said, "Will we be going to the tea party and getting a biscuit?" He was only thinking about the biscuit. They used to give it to you in the house. You'd go to the door and they'd be giving the biscuits out.' [Roberts, 1989: 201, quoting informant Mrs Shuttleworth (S3L)]

Further Reading

T.W. Carrick 'Scraps of English folklore: Cumberland' Folklore vol. 40, no. 3 (September 30, 1929) pp 278-290

E. Sidney Hartland 'Collectanea: Avril-bread', Folklore , vol. 28, no. 3 (September 30, 1917) pp. 305-310 [link to JSTOR paper]

Bertram S. Puckle 1926 Funeral Customs: their origin and development London T. Werner Laurie Ltd

Elizabeth Roberts 1989 'The Lancashire way of death' in Ralph Houlbrooke [ed] Death, Ritual and Bereavement Routledge, London

T.W. Thompson 'Collectanea: Arval or Avril Bread' Folklore vol. 29, no. 1 (March 30, 1918) pp 84-86