Primitive Warfare 2 1868

The Journal of the Royal United Service Institution

Vol XII 1868 No. LI.

LECTURE

----

Friday, June 5th, 1868.

General Sir WILLIAM J. CODRINGTON, G.C.B. in the Chair.

PRIMITIVE WARFARE, SECTION II. ON THE RESEMBLANCE OF THE WEAPONS OF EARLY MAN, THEIR VARIATION, CONTINUITY, AND DEVELOPMENT OF FORM.

By Colonel A.H. Lane Fox, late Grenadier Guards.

General Remarks.

In June, 1867, I had the honour of reading* a paper at this Institution, which has since been published in the Journal, the object of which was to point out the resemblance which exists between the weapons of savages and early races and the weapons with which nature has furnished animals for their defence.

In continuation of the same subject, my present communication will relate to the resemblance to each other of the weapons of races sometimes widely separated, and of which the connexion, if it ever existed, has long since been consigned to obscurity. I shall endeavour to show, how in these several localities, which are so remote from one another, the progress of form has been developed upon a similar plan, and, though to all appearance independently, yet that under like conditions like results have been produced; and that the weapons and implements of these races will sometimes be found to bear so close a resemblance to each other, as often to suggest a community of origin, where no such common origin can have existed, unless at the very remotest period.

We shall thus be brought to the consideration of the great problem of our day, viz. the origin of mankind, or rather the origin of the human arts; for the question of man's origin, whether he was himself created or developed from some prior form, whether since the period of his first appearance he has by variation separated into distinct races, or whether the several races of mankind were separately created, are questions which, however closely allied, do not of necessity form part of our present subject. It has to deal solely with the origin of the arts, and more particularly with the art of war, which in the infancy of society belonged to a condition of life so constant and universal as to embrace within its sphere all other arts, or at least to be so intimately connected with them as to require the same treatment; the tool and the weapon being, as I shall presently show, often identical in the hands of the primaeval savage.

These prefatory remarks are necessary because it will be seen that the general observations I am about to offer on the subject are fully as applicable to the whole range of the industrial arts of mankind as to the art of war. My illustrations, however, will be taken exclusively from weapons of war.

Is not the world at the present time, and has it not always been, the scene of a continuous progress? Have not the arts grown up from an obscure origin, and is not this growth continuing to the present day ?

This is the question which lies at the very threshold of our subject, and we must endeavour to treat it by the light of evidence alone, apart from all considerations of a traditional or poetic character.

I do not propose here to enter into a disquisition upon the functions of the human mind. But it must I think be admitted, that if man possessed from the first the same nature that belongs to him at the present time, he must at the commencement of his career in this world have been destitute of all creative power. The mind has never been endowed with any creative faculty. The only powers we possess are those of digesting, adapting, and applying, by the intellectual faculties, the experience acquired through the medium of the senses. We come into the world helpless and speechless, possessing only in common with the brutes such instincts as are necessary for the bare sustenance of life under the most facile conditions; all that follows afterwards is dependent purely on experience.

Whether we afterwards become barbarous or civilized, whether we follow a hunting, nomadic, or agricultural life, whether we embrace this religion or that, or attain proficiency in any of the arts, all this is dependent purely on the accident of our birth, which places us in a position to build upon the experience of our ancestors, adding to it the experience acquired by ourselves. For although it is doubtless true that the breeds of mankind, like the breeds of our domestic animals, by continual cultivation during many generations, have improved, and that by this means races have been produced capable of being* educated to a higher degree than those which have remained uncivilized, this does not alter the fact that it is by experience alone, conscious or unconscious, self-imposed or compulsory, and by a process of slow and laborious induction, that we arrive at the degree of perfection to which, according to our opportunities and our relative endowments, we ultimately attain.

The amount, therefore, which any one individual or any one generation is capable of adding to the civilization of their age must be immeasurably small, in comparison with what they derive from it.

I could not perhaps appeal to an audience more capable of appreciating the truth of these remarks than to the members of an Institution, the object of which is to examine into the improvements and so-called inventions which are from time to time effected in the machinery and implements of war.

How often does any proposal or improvement come before this Institution which after investigating its antecedents is found to possess originality of design? Is it not a fact that even the most ingenious and successful inventions turn out on inquiry to be mere adaptations of contrivances already existing, or that they are produced by applying to one branch of industry the principles or the contrivances which have been evolved in another? I think that no one can have constantly attended the lectures of this or any similar Institution, without becoming impressed, above all things, with the want of originality observable amongst men, and with the great calls which, even in this age of cultivated intellects and abundant materials to work upon, all inventors are obliged to make upon those who have preceded them.

Since, then, we ourselves are so entirely creatures of education, and derive so little from our own unaided resources, it follows that the first created man, if similarly constituted, having no antecedents from which to derive instruction, could not, without external aid, have made any material or rapid advance towards the initiation of the arts.

So fully has the truth of this been recognized by those who are not themselves advocates for the theory of development, that in order to account for the very first stages of human progress they have found it necessary to assume the hypothesis of supernatural agency: such we know was the belief of the classical pagan nations, who attributed the origin of many of the arts to their gods; such we know to be the tradition of many savage and semi-civilized nations of modern times that have attained to the first stages of culture. But we have already disposed of this hypothesis at the commencement of these remarks, by deciding that our arguments should be based solely upon evidence. We are, therefore, under the necessity of assuming, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, that none but the agencies which help us now were at the disposal of our first ancestors, and the alternative to which we must have recourse is that of supposing that the progress of those days was immeasurably slower than it is at present, and that vast ages must have elapsed after the first appearance of man before he began to show even the first indications of a settled advance.

Yet the complex civilization of our own time has been built on the foundations that were laid by these aborigines of our species, while the brute creation may be said to have produced little more than was necessary to their own wants or those of their immediate offspring. Man has been the agent employed in a work of continuous progression. Generation has succeeded generation, and race has succeeded race, each contributing its quota to the fabrication of the edifice, and then giving place to other workmen. But the progress of the edifice itself has never ceased; it has gone on, I maintain (contrary to the opinion of some writers of our day), always in fulfillment of one vast design. It is a work of all time.

To study it comprehensively, we must devote ourselves to the contemplation of the edifice itself, and set aside the study of mankind for separate treatment, for it is evident that man has been fashioned, not as the designer, but simply as the unconscious instrument of its erection. Each individual has been impelled by what—viewed in this light—may be regarded as instincts sufficient to stimulate him to labour, but falling- immeasurably short of a comprehensive knowledge of the great scheme, towards which he is an unconscious contributor. Of this he knows no more than the earthworm knows it to be its function to cover the crust of the earth with mould, or the small coral polypus knows that it is engaged in the erection of a barrier reef. No comprehensive scheme of progress need be searched for in the pigmy intellect of man, and if we are ever destined to acquire any knowledge of the laws which influence the growth of civilization, we must look for them in an investigation of the phenomenon itself, by studying its phases and the sequence of its mutations. In short we must apply to the whole range of human culture, to the arts, whether of peace or war, the same method which has already been applied with some success to the history of language.

It has been shown that the speech of our own day has been the work of many generations and of innumerable distinct races its roots are traceable in the utterances of the untutored savage. No nation ever consciously invented a grammar, and yet language has been shown to be capable of being treated as a science of natural growth, having its laws of mutation and development, never dreamt of by any of the many myriads of individuals that have unconsciously contributed to the formation of it. May not all the products of human intellects in the aggregate be made amenable to the same treatment, and, like language, be found to be influenced by laws of evolution and progress?

That these remarks are not merely speculative, that the progress of civilization has been continuous and connected, while the races which have been engaged in the formation of it, like individuals, have had their periods of birth, maturity, and decay, is sufficiently proved by history.

In Egypt and in Assyria, we see the remains of ancient and formerly populous cities, where now the nomadic Arab pitches his tent or wanders with his flocks, thus showing that relapses of civilization must have occurred in those particular localities where such phenomena are observed. But we know also from history that the civilization which once flourished in those countries did not expire there, but was transferred thence to other places; that the culture of Assyria and of Egypt passed into Greece and developed there; that from Greece it extended to Rome, and in the hands of a new people passed through fresh phases; that after the destruction of the Roman Empire it lay dormant for many ages, only to rise again on its original basis, extended and fertilized by the introduction of fresh blood; that we ourselves are the inheritors of the same arts, customs, and institutions, modified and improved; and finally, that civilization, expanding in all directions, as it continues to move westward, is now in process of being received back by those ancient countries in which it originated, in a condition far more varied and diversified than it could ever have become, had it been confined to a single people or country.

Passing now from the known to the unknown, we come to the study of prehistoric times, prepared to find that every fresh discovery helps us to trace backwards the arts of mankind in unbroken continuity towards their source.

Commencing with the Saxon and the Celt, and passing from these to the lake dwellers, and on to the inhabitants of caves, races whose successive periods of existence are determined chiefly by the animals with which their remains are associated, we find that, according to their antiquity, they appear to have lived in a lower and lower condition of culture, until in the drift period, coeval with the extinct mammoth and the woolly haired rhinoceros, we find the earliest traces of man, scanty and unsatisfactory though they be, yet sufficient to show that he must have existed in a state so rude, as to have devised no better implements than flints pointed at one end, and held in the hand.

These successive pre-historic stages of civilization have been divided into the stone, the bronze, and the iron ages of mankind. The evidence upon which this classification is based, has been so ably set forth in the works of Sir John Lubbock and others, that I need not refer to it further than to state that, in my treatment of the origin and development of the weapons of war, I shall in a great measure follow the same arrangement. But I shall endeavour to trace the development of form rather than the material of weapons, and to show by examples taken from various distinct periods, and especially by illustrations taken from existing savages, the various agencies which appear to have operated in causing progression during the earliest ages of mankind.

Of these, the first to be considered is undoubtedly the utilization and imitation of natural forms. Nature was the only instructor of primaeval man.

In my previous paper, I discussed this subject at some length, giving many examples in which the weapons of animals have been employed by man. But besides these weapons derived from animals, primaeval man must no doubt at first have employed the natural forms of wood and bone, and of stones either fractured by the frost, or rolled into convenient forms upon the seashore.

This principle of the utilization and imitation of natural forms appears to bear precisely the same relationship to the development of the arts, that, in the science of language, onomatopoeia has been shown to bear to the growth and development of articulate speech. In the attempt to trace language to its origin, onomatopoeia, or the imitation of the sounds of animals and of nature, appears not only to have been the chief agent in initiating the growth of language, but it has also served to enrich it from time to time, so that even to this day, poetry and eloquence in a great measure depend on the employment of it. But apart from this, language has had an independent and systematic growth of its own.

So, in like manner, men not only drew upon nature for their ideas in the infancy of the arts, but we continue to copy the forms and contrivances of nature with advantage to this day. But apart from this, we must look for an independent origin and growth, in which form succeeded form in regular continuity. Many a lesson has still to be learnt from the book of nature, the pages of which are sealed to us until, by the natural growth of knowledge, we acquire the power of reading and applying them. Imitation therefore, though an important element in the initiation of the arts, would not alone be sufficient to account for the phenomenon of progress.

The next principle which we shall have to consider, is that of variation. Amongst all the products of the most primitive races of man, we find endless variations in the forms of their implements, all of the most trivial character. A Sheffield manufacturer informed me, that he had lately received a wooden model of a dagger-blade from Mogadore, made by an Arab, who desired to have one of steel made exactly like it. Accordingly my informant, thinking that he had found a convenient market for the sale of such weapons, constructed some hundreds of blades of exactly the same pattern. On arriving at their destination, however, they were found to be unsaleable. Although precisely of the type in general use about Mogadore, all of which to the European eye would be considered alike, their uniformity rendered them unsuited to the requirements of the inhabitants, each of whom piqued himself upon possessing his own particular pattern, the peculiarity of which consisted in having some almost imperceptible difference in the curve or breadth of the blade.

In the earliest stages of art, men would of necessity be led to the adoption of such varieties by the constantly differing forms of the materials in which they worked. The uncertain fractures of flint, the various curves of the trees out of which they constructed their clubs, and the different forms of bones, would lead them imperceptibly towards the adoption of fresh tools. Occasionally some form would be hit upon, which in the hands of its employer would be found more convenient for use, and which, by giving the possessor of it some advantage over his neighbours, would commend itself to general adoption. Thus by a process, resembling what Mr. Darwin, in his late work, has termed ‘unconscious selection’ rather than by premeditation or design, men would be led on to improvement. By degrees some forms would be found best adapted to one pursuit, and some to another; one would be used for grubbing up roots, another for breaking shells, another for breaking heads; modes of procedure, accidentally hit upon in one class of occupation, would suggest improvements in another, and thus analogy, coming to the aid of accidental variation, would give an impulse to progress. Thus would commence that ramification of the arts, occupations, and sciences which, developing simultaneously and assisting each other, has borne fruit in the civilization of our own times.

I am aware that it will be found extremely difficult to realize a condition of human existence so low as that which I am supposing, and that many persons will deny the possibility of mankind having ever existed in a condition so helpless as to have been incapable of designing the simple weapons which we find in the hands of savages at the present day. It is as difficult to place one's self in the position of a being infinitely one's inferior, as of a being greatly one's superior in intellect. “Few persons” says Professor Max Müller, “understand children, still fewer antiquity.” Our own experience cannot save us in estimating the powers of either, for, long before the period of which we have the earliest recollection, we had ourselves undergone a course of unconscious education in the arts of a civilized community; our very first utterances were in a language which was in itself the complex growth of ages, and the improvement of our natural faculties, resulting from the continued cultivation of our race, enhances the difficulty we find in appreciating the condition of our first parents.

Another fertile source of variation arises from errors in successive copies. At a time when men had no measures or other appliances to assist them in copying correctly, and were guided only by the eye, an implement would soon be made to assume a very different appearance. Mr. Evans has shown in his work on the ' Coins of the Ancient Britons,’ how the head of Medusa, copied originally from a Greek coin, was made to pass through a series of apparently meaningless hieroglyphics, in which the original head was quite lost, and was ultimately converted into a chariot and four. We must not, however, attribute all variation to this cause, for I quite agree with a remark made by Mr. Rawlinson in his 'Five Great Monarchies', that such varieties are more frequently noticed in cases where the contrivance is of home growth, than in those which are derived from strangers.

The third point which we shall have to consider in relation to continuity, is the retarding element. Under this head, incapacity must at all times, and especially in the infancy of society, have played the chief part. But as civilization progressed, other agencies would come in to influence the same result; prejudice, force of habit, principles of conservatism in which we have been told by Mr. Mill that all the dull intellects of the world habitually ensconce themselves, a thousand interests of a retarding tendency, rise up at the same time as those having a progressive influence, and prevent our advancing by other than well-measured paces.

The resultant of these contending forces is continuity. If we could but put together the missing links; if we could revive contrivances that have died at their birth, and expose piracies if we could penetrate the haze that is so often thrown over continuity by great names, absorbing to themselves the credit of contrivances that belong to others, and thereby causing it to appear that progress has advanced with great strides, where creeping was in reality the order of the day; we should find that there is not a single work of man's hand which has not its history of slow and continuous development, capable of being traced back, like branches of a tree, to its junction with others, and so on until the roots of all are found to lie in the simplest contrivances of primaeval man.

But we must not expect that we shall be able, in the existing state of knowledge, to trace this continuity from first to last, for the links that are lost far exceed in number those which remain. The task may be compared to that of putting together the fragments of a tree that has been cut up for firewood, and of which the greater part has been burnt. It is only here and there, after diligent search, that we may expect to find a few pieces fitting in such a manner as to prove that they belonged to the same branch. We do not, on that account, abandon our conviction that the tree once grew, that every large branch was once a small twig, and that every limb developed by a natural process into the form in which we find it. The difficulty we have to contend with is precisely that which the geologist experiences in tracing his palaeontological sequence. But it is far greater, for natural history has been long studied, and the materials upon which Mr. Darwin founds his celebrated hypothesis have been in process of collection for many generations. But continuity, in relation to the arts, can scarcely yet be said to be established as a science. The materials for the science have not yet been even classified, and classification is a process which must always precede continuity in the study of nature. Classification defines the margin of our ignorance; continuity results from the extension of knowledge, by bridging over the distinction of classes. Travellers, for the most part, have been in the habit of bringing home, as curiosities, the most remarkable specimens of weapons and implements, without much regard to their history or the evidence they convey; and their descriptions of them, as a general rule, have been extremely meagre. Until quite recently, the curators of our ethnographical museums have aimed more at the collection of unique specimens, serving to exhibit well-marked differences of form, than such as by their resemblance enable us to trace out community of origin. The arrangement f them has been almost universally bad, and has been calculated rather to display the several articles to advantage, on the principle of shop windows, than to facilitate the deductions of science. The antiquities of savage races, moreover, have as yet been almost wholly unstudied.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, we are able to catch glimpses of evidence, here and there, which, when put together systematically, and when the vestiges of antiquity are illustrated by the implements of existing savages, will, I trust, be found sufficient to warrant the principles for which I contend.

Combination of Tool and Weapon.

In the earliest ages of mankind, when all men were warriors, and before the division of labour, consequent on civilization, had separated the arts of peace and war into distinct professions, we must expect to find the same implement frequently employed in the capacity of both tool and weapon. Even long after the very earliest ages of which we have any historical or archaeological record, we often find a combination of tool and weapon in the same forms, especially amongst those semi-civilized and savage races of our own times, whom we regard as the representatives of antiquity. The battles of liberty, from the age of the Jews and Philistines down to the time, of the last Hungarian revolution, have always been fought by the subject people with weapons made out of the implements of husbandry. We read in the first of Samuel, chapter xiii, 'Now there was no smith found in all the land of Israel: for the Philistines said, Lest the Hebrews make them swords or spears: but all the Israelites went down to the Philistines, to sharpen every man his share’ (the blade of the ploughshare), 'and his coulter' (a kind of knife), ‘and his ax, and his mattock' (a kind of pickaxe) … ‘So it came to pass, in the day of battle, that there was neither sword nor spear found in the hand of any of the people that were with Saul and Jonathan/ In the revolts of the German peasantry, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the bands of insurgents armed themselves with threshing flails and scythe blades. In 1794 and 1831, the Polish peasantry were similarly armed [1] and it was from such implements of husbandry that weapons like the military flail, the bill, and the yataghan, derived their origin. In the recent outbreak in Jamaica (which, had it not been ably and powerfully put down, would have led to the destruction of the whole white population) the negroes armed themselves with weapons of husbandry. In the proclamation of Paul Bogle, he says: 'Every one of you must leave your house, take your guns; who don't have guns, take cutlasses.’ The cutlasses here referred to were the implements used for cutting the sugar-cane, sharp on the concave edge, and are the same which, having been used as weapons by the negroes in their own country, have continued to be employed by them ever since. In like manner, we learn from Symes's 'Embassy to Ava in 1795’, [2] that the Burmese use the sabre both for warlike purposes, as well as for cutting bamboos, felling timber, &c.; it is the constant companion of the inhabitants for all purposes, and they never travel without it. In Borneo, the peculiar sword-like weapon, called the 'parangilang', is used both as a weapon, and also for felling trees, and the axe of this country is constructed so that, by turning it on the helve, it can be used either as a weapon or as a carpenter's axe. In like manner, the Kaffir axe-blade, by simply altering its position in the handle, is used either as a weapon, or for tilling the ground. The North American Indian tomahawk, like the Kaffir axe, is used for many different purposes; the spear-head of the Kaffir assegai is the knife that is used for all purposes of manufacture, and Captain Grant says that the Watusi of East Central Africa make all their baskets with their spear-heads. [3] The weapons edged with sharks' teeth, to which I referred in my former paper, are used in the Marquesas and other of the South Sea Islands, as much for cutting up fish and carcasses as for warlike purposes. [4] Dr. Klemm, in his valuable work on savage and early weapons, describes the wooden pick used by the inhabitants of New Caledonia both as a weapon, and also for tilling the ground, and he gives reasons for supposing that in Egypt and many other parts of the world, the form of the plough was originally derived from that of the hatchet or hoe, used for tilling purposes. The hoe used in East Central Africa, which also, like the Kaffir axe, serves as a medium of exchange in lieu of money, evidently derived its form from that of a spear or arrow head. The spade, formerly used in this country, and represented in old pictures, which is still used as a shovel in Ireland, is a pointed spear-like instrument, and the 'loy' or spade still used in all parts of Ireland is hafted exactly in the same manner as the bronze celt of prehistoric times. Dr.Klemm gives an illustration of an axe used by the Norwegian peasants both as a tool and weapon. Speke describes the Usoga tribe as being armed with huge short-handed spears, adapted rather for digging than for war; and Barth describes the Bornouese troops in Central Africa digging holes with their spears, and employing them in searching for water. The Australian ‘dowak’, a kind of club with a flint attached, combines the purposes of a tool and weapon. We know from the short sticks upon which the small arrow-heads of quartz found in the Peruvian tombs are mounted, that they must have been used as knives as well as for missile purposes. Professor Nilsson says that flint-barbed arrow-heads, of precisely the same form, are used by the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego as knives,3 and Mr. Stephens, in his travels in Central America, shows reason for supposing that the large stone idols in Copan were carved with similar arrow-points, [5] no other instrument capable of being used for such a purpose having been found in the neighbourhood.

Examples of this class of evidence might be multiplied ad infinitum; but enough has already been said to afford good grounds for believing that many of the implements of stone and bronze which are found in the soil, may have been used for a great variety of purposes, and that, especially in the earliest stages of culture, we must be careful how we attribute especial purposes to tools and weapons because they appear to differ from each other slightly in form. This is more especially so when, as is almost invariably the case, the several distinct types are found—when a sufficient number of them are collected and arranged—to pass almosts imperceptibly into each other by connecting links; showing that the differences observable between any two implements of the same class, when brought together and contrasted, are rather due to the operation of a law of variation and development in the fabrication of the tool itself, than to an intention on the part of the constructor to adapt it to particular purposes, and that its application to such especial purposes must have followed, rather than itself have influenced, the development of the tool.

Transition from the Drift to the Celt Type. (Plate XVII)

My first illustration must of necessity be taken from the flint implements of the drift, the earliest records of human workmanship that the researches of science have as yet revealed to us. These, to use the words of Sir Charles Lyell, 'were probably used as weapons both of war and the chase, to grub roots, cut down trees, or scoop out canoes.’ [6]

I will not attempt during the brief time allotted to me on the present occasion, any detailed account of the evidence of the antiquity of these weapons, assuming that the works of Sir Charles Lyell, and Sir John Lubbock, will have rendered this subject more or less familiar to most persons at the present day, but I will confine myself to pointing out the indications of variation and of improvement observable in the implements themselves.

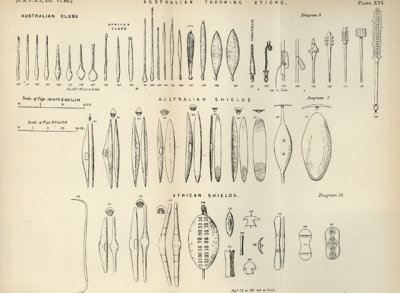

I have arranged upon Sheet No. 1 of illustrations (Plate xvii) a series of specimens of the same type from nearly every part of the globe.

All the figures given in these diagrams are traced from the implements themselves, and reduced by photography; they may therefore be regarded as facsimiles, a point of great importance when our subject has to deal with the minute gradations of difference observable between them. Figures 1 to 11 are of the drift type. Casts of the originals of some of them, and specimens of the implements themselves, are also upon the table for comparison.

I may here acknowledge the great obligation I am under to Mr. Franks for the facilities he has afforded me in drawing many of these specimens in the Christy Collection; to Dr. Watson for a similar permission in regard to the valuable collection of arms in the India Museum; and also to Dr. Birch of the British Museum. A large proportion of my illustrations are taken from the excellent Museum of this Institution, and others are from my own collection.

Of the drift specimens which I have selected to illustrate the diagrams, five are from the gravel beds of St. Acheul, in order that we might have an opportunity of observing the variation in implements derived from the same locality, and probably belonging to the same or nearly the same period—chips in fact from the same workshop.

It has been usual to classify these drift implements in two divisions; the spear-head form, and the oval form. Of the first or spear-head form, figures 2 to 4 are typical examples; of the oval form, figure 8 is the best illustration. I venture, however, to think that a distinction more clearly embodying a principle of progress may be made by dividing them differently, and by placing in the first class those which are either left rough or rounded at one end and pointed at the other, of which figures 1 to 7 are examples; and in the second class, such as are chipped to an edge all round, of which figures 8 to 11 are types. My reason for preferring this classification to one dependent on outline is this. The first class having the natural outside coating of the flint or a roughly rounded surface on one side, appears to be in every way adapted to be held in the hand; whereas the second class, of which a beautiful specimen in the Christy Collection from St. Acheul is represented in a front and side view in figure 10, could not conveniently be used in the hand as a tool or weapon, without injury to the hand from the sharp edge with which its periphery is surrounded on all sides. If, therefore, we see reason for supposing that one class of implements was employed in handles, whilst the other may have been used in the hand, I think this constitutes a more important distinction, and one more obviously implying progress, than a classification which merely involves a modification of outline, which may have resulted from no more significant cause than a difference in the form of the flint nodule out of which the implement was made. [7]

Another important distinction between these drift implements as thus arranged, arises from the different purposes to which they may have been put by the fabricators. The first class, figures 1 to 7--it will be seen by the side view of them—could have been used only as spears, picks, or daggers, the pointed or small end being employed for that purpose, whereas the latter class, figures 8 to 11, are equally available for use as axes with the sharp and broad end. It is quite possible therefore, that we may see here, in these vestiges of the first tools of mankind (specimens of all varieties of which are found in the same beds at St. Acheul), the point of divergence between the two distinct classes, which must certainly be regarded as the two most constant and universal weapons of mankind in all ages and countries of the world, viz. the spear and the axe; the small end developed into the spear and in to all that class of tools for which a point is required; and from the broad end we obtained the axe and all those tools which either as chisels, choppers, gouges, or battle-axes, have continued in use with an endless continuity of development and modification, and a world-wide history up to the present time. I am aware that in the St. Acheul implements, as well as in those of similar form from the laterite beds of Madras, we find occasionally specimens in which the small end is made broader, as if indicating the gradual development of an edge on that side, but upon the whole I think the balance of evidence is in favour of the broad end having originated the axe form.

Nothing, it will be seen, can be more primitive than these tools, or more gradual than their development. They are perfectly consistent with the idea that the fabricators of them were in a condition closely verging upon that of the brutes. Apes are known to use stones in cracking the shells of nuts. The advantage to be derived from a pointed form, when it accidentally fell into the hand, would suggest itself almost instinctively to any being capable of profiting by experience and retaining it in the memory. Accidental fractures, producing a sharp edge, would lead to fractures of design, and thus we may easily suppose that such implements as are represented in the first few figures of our diagram must necessarily have resulted from the very earliest constructive efforts of primaeval man.

From the very first, a peculiar mode of fabrication appears to have been adopted, which consisted of chipping off flakes from alternate sides of the flint, and the facets thus left upon the flint produce the wavelike edge which you will see in the side views of all the implements here represented. This method continued to be employed throughout the entire stone age, in all parts of the universe, and is characteristic not merely of the drift, but of the cave, pfahlbauten, and surface periods.

The numerous intermediate gradations of form, whether between the oval and the spear-head form, or between the thick and the sharpened form, have been noticed by Sir Charles Lyell. By selecting specimens, and arranging them in order from left to right, I have endeavoured to trace the transition from the drift type to the almond-shaped celt type, which latter is common to the stone age of mankind, whether ancient or modern, in all parts of the world.

Had the discovery of drift implements been confined to one locality or to one district, it is probable it would have attracted but little notice. As early as the first year of the present century the attention of the Society of Antiquaries had been drawn by Mr. Frere to the existence of these implements, in conjunction with the remains of the elephant and other extinct animals at Hoxne in Suffolk. An illustration of the specimens from this locality is given in figure 4. Mr. Frere described them as 1 evidently weapons of war, fabricated and used by a people who had not the use of metals.’ But little or no attention was paid to the subject until the discovery by M. Boucher de Perthes of precisely similar implements associated with the same class of remains, in the drift gravel of St. Acheul, near Amiens, in 1858. [8] Since then many other discoveries have been made, and still continue to be made, by Mr. Prestwich, Mr. Evans, Mr. Flower, Mr. Bruce Foote, and others, not only in this country but also in Asia and Africa, showing, in so far as the discoveries have hitherto gone, that this drift type, like the almond celt type, is common to the earliest ages in all parts of the world, and that everywhere the drift type preceded the almond-shaped celt type, and is found in beds of earlier formation.

Figure 5 is a drift-shaped implement from the laterite beds of Madras, of exactly the same form as those found in England. Figure 6 is an implement of the same class from the Cape of Good Hope, found fourteen feet from the surface. In America, implements of the drift type have not yet been discovered, but stone spear-heads have been found in Missouri in connexion with the elephant and other extinct animals. Figure 11 is from a mound of sun-dried bricks at Abou Sharein, in Southern Babylonia, obtained by Mr. J. E. Taylor, British Consul at Basrah it is a chipped flint; in form it is of the drift type, and its outline is precisely that of some of the Carib celts found in the West India Islands; it also closely resembles in form others from the Pacific [9]; its edge was evidently at the broad end. Another of the same type was found at Mugeyer in Babylonia, and a third closely resembling the two former was found in a cave in Bethlehem.

The celt type has not as yet been found in the French caves of the reindeer period, but it is common in the 'pile dwellings' of the Swiss lakes. Some of the French cave specimens, however, closely approach the drift form, and in place of the celt, we have a peculiar kind of tool trimmed to a cutting edge on one side and having the other round for holding in the hand. As, however, these do not fall into the direct line of development, but may be regarded as a branch variety, I have not figured them in my diagram, but pass at once, though almost imperceptibly as regards form, from the drift to the surface type.

Figure 12 formed part of a large find of flint implements, discovered by myself in the ancient British camp of Cissbury, near Worthing—an account of this discovery was communicated by me to the Society of Antiquaries at the commencement of the present year. The period of these Cissbury implements must be fixed at a very much more modern date than those of the drift, with which they are associated in my diagram, having been found in conjunction with the earliest traces of domestic animals, such as the Bos longifrons, Capra hircus, and Sus they may, however, be classed with the stone age, no trace of metal having been discovered with them, although from 500 to 600 flint implements were found in the camp. The peculiarity of the Cissbury find, however, consists in the discovery (in the same pits in which celts of the type represented in figure 12 were found) of a few flints closely approaching the drift type, being thick at the broad end, and also of a large number resembling those found in the French caves, trimmed to an edge on one side, and adapted to be held in the hand. So that the Cissbury find, although belonging to what is usually called the surface period, contains specimens affording every link of connexion between the drift and the almond-shaped celt type. This discovery must, I think, be regarded as a step in knowledge of prehistoric antiquity, and a decided accession to the science of continuity, for Sir John Lubbock has told us in his preface to the work of Professor Nilsson, lately published [10], that the Palaeolithic, i.e. the drift types, 'have never yet been met with in association with the characteristics of a later epoch.' I shall therefore be interested to know whether, after an examination of the Cissbury specimens, which I have presented to the Christy Collection, Sir John Lubbock may be induced to alter his opinion on that point; for I think it is entirely consistent with all that is known of early races of mankind, that early types should be retained in use long after the introduction of others that have been developed from them. However this may be, I think that in casting the eye from left to right along the upper row ..., it will puzzle the acutest observer to determine where the drift type ends, and that of the celt begins. If it is contended, as I am aware it will be contended by some, that the typical characteristic of the celt consists in its being sharp at the broad end, while those of the drift are blunt at the broad end, I reply that many of the drift specimens are also sharpened at the broad end, more especially those represented in figures 9 and 10 from the drift of St. Acheul. Many specimens from Thetford which I have seen, as, for example, Fig. 17 b, from a cast in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries, presented by Mr. Flower, approach equally closely to the celt type, as do some of those from the laterite beds of Madras, and though they are of rare occurrence in all these localities, and are certainly a variation from the normal type of drift implements, still they are found in sufficient numbers to serve as links in connecting the forms of the earliest, with those of the later period.

I have dealt somewhat at length upon this part of my subject, owing to the circumstance of its presenting some features of novelty in the study of flint implements, and being therefore open to criticism on the part of those who are more favourable to the principles of classification than of continuity, with all the important concomitants, of division versus unity, which those principles involve.

I may now pass briefly over the remaining figures in the diagram. Figure 13 is a specimen found by Mr. Evans at Spienne, near Mons; its very close resemblance to figure 12 from Cissbury will be noticed; in fact the whole of the Spienne specimens resemble very closely those discovered in Cissbury, except that the Spienne implements of this class are associated with others of polished flint, which gives them a more advanced character than those derived from Cissbury, in which place only one fragment of a polished implement was discovered, and that in a part of the intrenchment which renders it very doubtful whether it ought to be associated with the Cissbury find. Figures 15, 16, and 17 are from Denmark, Ireland, and Yorkshire;—this type, however, is rare in Denmark, most of the flint implements from that country being of a more advanced character, and having usually a rectangular cross-section.

The lower row of the diagram consists of specimens derived, either from what has been termed the neolithic or polished stone age of Europe, or from savages who are still in a corresponding stage of progression in various parts of the world at the present time.

To the former or neolithic stone age of Europe belong figure 21 from France, figure 25 from the bed of the Clyde in Scotland, figure 27 from the Swiss lake-dwellings, figure 29 from the caves in Gibraltar, figure 30 from Sweden, figure 36 from Portugal, figure 37 from the bed of the Thames, figure 38 from Ireland, figure 39 from Jelabonga, in Russia. Precisely identical forms are also found in Germany, Italy, and the Channel Isles. Amongst the specimens derived from the ancient stone age of other parts of the world, and belonging to an age of civilization that is now extinct, may be enumerated figure 22 from Peru, figure 40 from Mexico, figure 24 from Central India, figure 41 from Japan, figure 42 from Mugeyer, in Babylonia. Nearly similar ones, but flattened at the side, like those common in Denmark, have been obtained from China and Pegu. Figure 43 is from Algeria, from the collection of Mr. Flower.

The following are examples of the same class of implements, used by savages of our own, or of comparatively modern times:—Figures 18 and 19 from Australia; these are generally used in a handle, formed by a withe twisted round them in the manner still used by blacksmiths in this country. Sometimes, however, I am informed by an eye-witness, the Australians use these celts in the hand without any handle at all. Although polished on the surface, these Australian celts have been compared by Sir Charles Lyell to the oval forms of the drift represented in figure 7. The art of polishing appears to have preceded the development of form in this country. Figure 20, from New Zealand, is a specimen in Mr. Evans's collection, of which he has been so kind as to allow me to take an outline; this form, however, is extremely rare in New Zealand, the usual shape of the stone celts from that country being flat-sided, like the specimens from Denmark, already noticed. Figure 23 is from the Pacific; figure 26, from Pennsylvania; these were used by the American Indians, previously, and for some time after the immigration of Europeans. Figures 31 and 32 are Carib celts from my collection, beautifully polished. Figure33, from St. Domingo, is in the Cork Museum. Figure 34, from the Antilles, is in the Christy Collection; both of these have a human face engraved upon them. Figure 35 is of jade, from New Caledonia, in my own collection.

Hafting.

The method of hafting these implements, employed by savages, shows that they were used for a variety of purposes; in some, the edge is fastened at right angles to the handle, to be used as an adze, whilst in others the same tool is fastened with the blade in a line with the handle, to be used as a chopper or battle-axe. In some it is fastened with a withe, passed round the stone, as in the specimen from Australia (fig. 44, from this Institution) and some parts of North America; figure 45 is a stone axe from the Ojibbeway Indians, from my collection. At other times it is inserted in the side of a stick or club. A specimen in my collection from Ireland (fig. 46), one of the few that have ever been found with handles, shows that this was the method employed in that country. [11] Others are inserted in the end of a bent stick (fig. 47), a mode of hafting common in the Polynesian Islands, in Africa, Ancient Egypt, Mexico, North America, and New Caledonia; it is employed by the Kalmucks and others, and was used during the bronze age. Some of the Australian axes were fastened to their handles by a peculiar preparation of gum manufactured for that purpose.

Dr. Klemm, in his 'Werkzeuge und Waffen', supposes the first lessons in hafting to have been derived from nature, by observing the manner in which stones are often firmly grasped by the roots of trees growing round them, and he gives several woodcuts of specimens of Nature's hafting, which he has collected from various sources; one of these, extracted from his work, is represented in figure 48. I have placed upon the table, in illustration of this idea, an iron mediaeval axe-head (fig. 49), which has furnished itself with a handle in this manner, whilst buried beneath the surface; it is said to have been found in Glemham Park, Suffolk, eleven feet from the surface. Even to this day, when a peasant in Brittany discovers one of these stone celts upon the ground, he is in the habit of splitting the branch of a young tree and inserting the celt into the cleft; in the course of a year or two it becomes firmly fixed, and he then cuts off the branch, and uses the implement thus hafted by nature as a hammer for driving nails. In the ‘Antiquites Celtiques et Antediluviennes’, M. Boucher de Perthes mentions the discovery of two ancient stone hammer-heads, which appeared to have been furnished with handles by passing the hole over the bough of a tree and allowing it to fill up the aperture by its natural growth, until it became fixed as a handle. [12]

It might be interesting, if space permitted, to follow up the, development of the stone axe-head through its various phases until, in the latest stages, when bronze had already come into general use for weapons, we find it furnished with a hole through the middle for the insertion of the handle. It may, I think, be safely said that—although nature furnishes numerous examples, in many classes of rocks, and especially in flints, of stones perforated with holes, and although they appear to have attracted the notice of the aborigines of many countries by the peculiar superstitious reverence which is often found to be attached to such stones when found in the soil—this mode of fastening stone implements in their handles did not come into use until late in the stone age, and that even in the bronze age it was but little employed.

Transition from Oval to Rectangular Forms.

Whether the stone celts having a square or rectangular section (such as are found principally in Denmark, New Zealand, Mexico, and Pegu), were coeval, or of subsequent development, to those of the almond-shape type, may be a matter for conjecture the small flint hatchets found in the Kitchenmiddens of Denmark appear to approach closely to the rectangular type. It is certain, that in the Swiss Lakes both forms are found fully developed, and it may be mentioned, as an instance of the constant tendency to variation that is everywhere observable in the weapons of the early races of mankind, that of the whole of the celts found at Nussdorf, in the Lake of Constance, though all might be traced to the same normal type as regards their general outline, no two were alike; and Dr. Keller gives sections, showing every conceivable gradation from the square and rectangular to the oval and circular section [13]. It may, however, be affirmed, that convex forms, as a general rule, preceded those having a rectangular or concave surface; it is so in the forms of nature; the habitations of animals are almost invariably convex. Dr. Livingstone mentions that he found it impossible even to teach the natives of South Africa to build a square hut; when left to themselves for a few minutes, they invariably reverted to the circle. All the earliest habitations of prehistoric times are found to be circular or oval; even the sophisticated infant of modern civilization, when he plays with his bricks, will invariably build them in a circular form, until otherwise instructed.

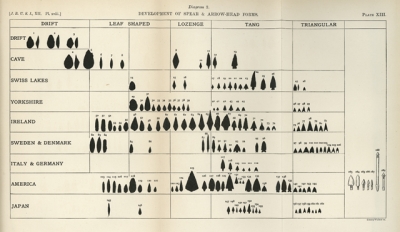

Development of Spear and Arrow-head Forms. (Plate XVIII)

We must now turn to the development of the second great class of weapons—the spear and arrow. These may be classed together, the arrow being merely the diminutive of the spear; and it may be taken as a general rule, applicable to all the arts of prehistoric times, that when a given form has once been introduced, it will speedily be repeated in every possible size that can be applied to any of the various purposes for which such a form is capable of being used. Size, in the arts of the earliest ages, is no indication of progress. In the same way it may be said of the development of the animal or vegetable kingdom, size is no indication of improved organism.

In the same beds in which the drift-type implements are found, flakes, either struck off in the formation of such tools, or especially flaked off from a core in a particular manner, indicating that they were themselves intended for use as tools, are found in considerable numbers. No more useful tool could have been used during the stone age than the plain, untouched flint flake, which, from the sharpness of the edge, is capable of being used for a variety of purposes. Those, for example, formed of obsidian are so sharp that it is recorded, by the Spanish historians, that the Mexicans were in the habit of shaving themselves with such flakes. As my present subject has to deal exclusively with war weapons, I will not enter into a detailed description of these flakes, further than to observe that they are found, together with the cores from which they were struck off, in every quarter of the globe in which flint, obsidian, or any other suitable material has been found, and that everywhere the process of flaking appears to have been the same.

Now, the fracture of flint is very uncertain; by constant habit, the ancient flint-workers appear to have been able to command the fracture of the flint in a manner that cannot be imitated, even by the most skilful forgers of those implements in modern times; but, notwithstanding this, the varieties of the forms of the flakes thus struck off must have been very considerable, and these varieties must, from the very first, have suggested some of the different forms of tools that were made out of them.

I cannot, perhaps, explain this point better than by exhibiting a number of flakes, found by myself in the bed of the Bann at Toom, in Ireland, at the spot where that river flows out of Lough Neagh. This was a place originally discovered by Mr. Evans, where probably, in a habitation built upon the river, they formerly manufactured flint implements; and the bed of the river for the space of a hundred yards or more is covered with the flakes. It will be seen on examining these flakes, that some of them came off in a broad leaf-shaped form, and these, with a very little additional chipping, have been formed into spear-heads. Others longer and thicker have been chipped into something like picks, and others thinner and narrower than the two former, have been used probably as knives; others for scraping skins. We see from this that certain forms would naturally suggest themselves through the natural fracture of the flint, and this may to a certain extent account, though it does not, I think, entirely account, for the remarkable resemblance of form and unity of development observable in the spear and arrow heads, derived from localities so remote from each other as almost to preclude the possibility of their having ever been derived from a common source.

I have arranged in tabular form, ... representations of spear and arrow heads from all the different localities from which I have been able to obtain them in sufficient number to show fairly the numerous varieties which each country produces. On the top of the diagram, from left to right, the several forms are arranged in the order that appears most truly to indicate progression; but it must not be supposed that this arrangement is absolutely correct, for the several forms, such for example as the tang and the triangular form, were most probably derived from a common centre. The specimens from each locality ought therefore, in order to display their progression properly, to be arranged in the form of a tree, branching from a common stem. On the left of the diagram are written the different periods and localities, from which the specimens are derived. Commencing with the drift—the oldest of which we have any knowledge—which is coeval with the elephant and rhinoceros in Europe, we have the peculiar thick form already described. The examples of the drift period here shown, from their small size, must evidently have been used with a shaft, as they are scarcely large enough to have served as hand tools. None of the lozenge, tang, or triangular forms, have ever been found in the drift.

The next line represents specimens from the French caves of the reindeer period, which are taken from the Reliquiae Aquitanicae, chiefly from Dordogne. It will be seen that in these caves the first rude indications of the lozenge and tang form are represented, but no perfect specimens of either class. No example of the triangular form has been discovered. The leaf-shape form, however, is well represented.

In the ancient habitations of the Swiss Lakes, which belong to a later period, all varieties, except those of the drift type, are represented, but none of them in their most fully developed form; the tangs, it will be seen, are long, and the barbs comparatively short; the triangular form, which I consider to be the latest in the order of development, is mentioned by Dr. Keller, from whose work these specimens are taken, as being extremely rare. The comparative rarity of flint implements in the Lakes may, however, in some measure be accounted for, by the absence of flint in the district, necessitating the importation of this material from a distance.

The specimens from Yorkshire, Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, and Germany, may be considered to carry the development of these forms up to the latest period, viz. the late stone, and early bronze age; for there can be no doubt from the number of arrow-heads found in these countries, in connexion with implements of bronze, that they were used for missile purposes long after the armes blanches had been constructed of metal.

In all these localities it will be seen that the various gradations of form are identical; but as I have been able to collect a much larger number of arrow-heads from Ireland than elsewhere, the development of form is more apparent in the specimens selected from that country.

From the leaf-shape, it will be observed, there is every link of transition into the perfect lozenge type, and the latter is as a general rule, both in Ireland and in Yorkshire, much rarer, and more carefully constructed, than the leaf-shaped type, showing that there is every probability of the lozenge having been an improved form.

The tang form is represented, at first, by a few rude chips on each side of the base of the original flake, narrowing that part in such a manner as to admit of its being inserted, into a handle or shaft, and bound round with a sinew. This is superseded by the gradual formation of barbs on each side, and these barbs are lengthened by degrees, until they reach to the line of the base of the tang; the tang subsequently shortens, leaving the barbs with a semicircular aperture between them, and thus approaching some of the forms represented in the triangular column. These latter barbed specimens are usually more finished, and chipped with greater care than the long-tanged ones, which are rougher, more time-worn, and probably of earlier date.

The triangular form is seen at first, with a straight base gradually a semicircular aperture appears, and this deepens by degrees until, in some of the more carefully formed specimens, it approaches the form of a Norman arch. This last variety is especially well represented in Denmark.

Sir William Wilde's arrangement, in his Catalogue of the Royal Irish Academy differs in some respects from this; he considers the triangular an early form, and he assigns the final perfection of the art of fabricating flint spear-heads, to the large lozenge-shape form; grounding his opinion on the circumstance of many of this form, of the larger size, having been found polished, whilst those of the leaf, triangular, and tang shape are not usually carried further than the preliminary process of chipping. But it is evident that these larger forms may have been used for spears, the lozenge shape being especially adapted for this purpose, as enabling the owner of it to withdraw it from the wound, after slaying his adversary; while those of the barbed and triangular form being lighter, and calculated to stick in the wound, would be better adapted for arrow-heads: and it is unlikely that the same amount of labour would be expended on a weapon intended to be cast from a bow, as upon one designed to be held in the hand. I consider the polishing of these particular weapons therefore to be no criterion of age, but merely to indicate that they were used as armes d'hast, and not as missiles.

It appears highly probable, however, that all the several varieties, if not developed simultaneously, were used at the same time; for we find amongst the Persians, the Esquimaux, and many other nations, that a great variety of arrow-heads are carried in the same quiver, and are used either indiscriminately or for different purposes. [14]

In the eighth row from the top, I have arranged a series of similar forms from America, obtained chiefly from Pennsylvania, but they are also found in other parts of the continent, and some few of the illustrations here given viz figures 131. 132 and 133 (pl. xviii) are from Tierra del Fuego. Their forms enable them to be arranged under precisely the same divisions as those from the continent of Europe, and in each division the same development is observable. The tang or barbed form, however, differs sufficiently from the European forms of the same class to show that they arose independently, and were not derived from a common source. The tang of the American arrow-heads, it will be seen, is broader, at least in the later forms, and it appears to have originated in a notch on the sides of the blade, intended to hold the sinew with which it is attached to the shaft or handle. This notch appears to have been constructed lower and lower on the sides of the blade, until at last it comes down quite into the base of the flint, and it then closely resembles the European in form; compare, for example, figures 94 and 136; except that the tang is broader, and has a lateral projection on each side, so as to render it firmer in the shaft when bound by the sinew.

Notches at the side of the blade are extremely rare in Ireland, but from Sweden Professor Nilsson gives a drawing of an arrow-head, which I have copied into my diagram, see figure 96 (pl. xviii). It is precisely identical, in its peculiar form, to one here figured from America figure 139 (pl xviii), and they both have a concave base, in addition to the side notch; thus apparently representing a transition form between the tang and the triangular, which I have never noticed, except in the two specimens here referred to, and which must be regarded in Europe as extremely rare.

To illustrate the mode of fixing these instruments in their shafts, I have here figured several examples from my collection; two of these figures 163 and 164 (pl xviii) were derived from the Esquimaux, between Icy Cape and Point Barrow, the person from whom I purchased them having brought them himself from that locality. Figures 165, 166, and 167, (pl xviii) are from California.

Burton says that the Indians between the Mississippi and the Pacific use the barbed form only for war and Schoolcraft, in the Archives of the Aborigines of America, gives illustrations of two methods of fastening, one for war and the other for the chase, the former being loosely tied on, so as to come off when inserted in the wound.

But, in addition to their use as arrow-points, we have reason to suppose that they were used also as knives. I have represented in the sheet figures 168 and 169 (pl xviii) two short-handled instruments from Peru, which are now in the British Museum, into which similar arrow-points are inserted. These, from the shortness and peculiar shape of their shafts, could hardly have been used as darts. The only weapon peculiar to those regions from which such an instrument could have been projected, is the blow-pipe, and they are entirely different from the darts used with the blow-pipe either in South America, the Malay Peninsula, or Ceylon, in which countries the blow-pipe is used. There is reason to believe, from the manner in which they are placed in the graves, unaccompanied by any bow or other weapon from which they could have been projected, [15] that they were employed as knives, and this is confirmed by the fact, already mentioned, of the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego using their arrow-points for knives. The great numbers in which they are found in Ireland, in Yorkshire, and other localities appertaining to the late stone age, in which places they form the greater part of the relics collected, and are always the most highly finished implements discovered—the other stone implements associated with them being either celts, flint-discs, picks, or rough or partially worked flakes, that are capable of being wrought into arrows—the fact that the peculiar modification of form observable at the base of these implements appears to have been designed rather to facilitate the attachment of them to their wooden shafts or handles, than for the special purposes of war; and the frequent marks of use, as if by rubbing, that are found on the points of many of them, especially in the specimens from Ireland all these circumstances favour the supposition that in Europe, as well as in America, these arrow-head forms were used for many other purposes besides war and the chase; and that, like the assegai of the Kaffir, and the many other examples of tool-weapons already enumerated, we may regard them as having served to our primaeval ancestors the general purposes of a small tool available for carving, cutting, and for all those works for which a fine edge and point was required. On the other hand the celt undoubtedly provided them with a large tool capable of being applied to all the rougher purposes, whether peaceful or warlike, for which it was adapted in the simple arts of an uncivilized people.

In the ninth row I have arranged, under their respective classes, the whole of the specimens of flint arrow-heads that are given in Siebold's atlas of Japanese weapons. [16] It will be seen that they present the same variety of form as those already described. A similar collection of flint arrow-heads has lately been added to the British Museum by Mr. Franks, and described by him. They formed part of a Japanese collection of curiosities, and are labelled in the Japanese character, showing that this remote country not only passed through the same stone period as ourselves, but that, as their culture improved and expanded, they, like ourselves, have at last begun to make collections of objects to illustrate the arts of remote antiquity.

Implements composed of Perishable Materials.

It is now time that I should say a few words respecting weapons constructed of more perishable materials; for it is not to be assumed that, because we find nothing in the drift-gravels but weapons of flint and stone, the aborigines of that age did not also employ wood and other materials capable of being more easily worked. If man was at that time, as he is now, a beast of prey, he must also have become familiar, in the very first stages of his existence, with the uses of bone as a material for fabricating into weapons. In the French caves, a large number of bone implements have been found, and their resemblance, amounting almost to identity, with those found in Sweden, amongst the Esquimaux, and the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, has been noticed by Sir John Lubbock, Professor Nilsson, and others.

But, in dealing with the subject of continuity and develoment, it is necessary to confine our remarks to those countries from which we have had an opportunity of collecting large varieties of the same class of implement; we must therefore have recourse to the Australian, the New Zealander, and those nations with which we are more frequently brought in contact.

Transition from Celt to Paddle, Spear, and Sword Forms. (Plate XIX)

The almond-shape celt form, as I have already demonstrated, is one so universally distributed and of such very early origin, that we may naturally expect to find many of the more complicated forms of savage implements derived from it. In a paper in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology a writer draws attention to the occurrence in the bed of the Bann, and elsewhere in the north of Ireland, of stone clubs, formed much upon the general outline of the celt, but narrowed at the small end, so as to facilitate their being held in the hand like a bludgeon. Fig. 50 is copied from the illustration given in the paper referred to, and fig. 51 is another in my collection, also from Ireland, of precisely the same form; the original is upon the table, and it will be seen that it is simply a celt cut at the small end, so as to adapt it to being held in the hand. Fig. 52 is an implement in common use among the New Zealanders, called the 'pattoo-pattoo', of precisely the same shape; it is of jade, and its form, as may be seen by the thin sharp edge at the top, is evidently derived from that of the stone celt. Fig. 53 is a remarkably fine specimen, from the Museum of this Institution; the handle part in this specimen is more elaborately finished. These weapons are used as clubs to break heads, and also as missiles, and the fact of their having been derived from the celt is shown by the manner in which they are used by the New Zealanders. I am informed by Mr. Dilke, who derived his information from the natives whilst travelling in New Zealand, that the manner of striking with these weapons is not usually with the side, but with the sharp end of the pattoo-pattoo, precisely in the same manner that a celt would be used if held in the hand. The spot selected for the blow is usually above the ear, where the skull is weakest. If any further evidence were wanting to prove the derivation of this weapon from the stone celt, it is afforded by fig. 54, which is a jade implement lately added to the British Museum from the Woodhouse Collection. It was, for some time, believed to have been found in a Greek tomb, but this is now believed by Mr. Franks to be a mistake; it is, without doubt, a New Zealand instrument. The straight edge shows unmistakably that the end was the part employed in using it, while the rounded small end, with a hole at the extremity, shows that, like the pattoo-pattoo, it was held in the hand. It is, in fact, precisely identical with the hand celts from Ireland, above described, and forms a valuable connecting link between the celt and pattoo-pattoo form. Now it may be regarded as a law of development, applicable alike to all implements of savage and early races, that when any form has been produced symmetrically, like this pattoo-pattoo, the same form will be found either curved to one side, or divided in half; the variation, no doubt, depending on the purposes for which it is used. The pattoo- pattoo, having been used at first, like its prototype the celt, for striking with the end, would naturally come to be employed for striking upon the side edge. [17] The other side would therefore be liable to variation, according to the fancy of the workman. Figs. 55, 56, and 57, are examples of these implements, in which the edge is retained only on one side and at the end, the other side being variously cut and ornamented. This weapon extended to the west coast of America, and there, as in New Zealand, they are found both of the symmetrical and of the one-sided form. Fig. 58 is one believed to be from Nootka Sound, in my collection. Fig. 59 is also from Nootka, in the Museum of this Institution. Fig. 60 is an outline of one from Peru, which is figured in Dr. Klemm's work, and I am informed that a nearly similar club has been derived from Brazil.

The same form as the pattoo-pattoo, in Australia, has been developed in wood. Fig. 61 is from Nicol Bay, North-West Australia, and is in the Christy Collection described as a sword. Fig. 62 is of the same form, also of wood, but of cognate form, from New Guinea. In fig. 63, which is also from New Guinea, we see the same form developed into a paddle. In the larger implements of this class we see the same form, modified in such a manner as to diminish the weight; thus, the convex sides become either straight or concave. I have arranged upon the walls a variety of clubs and paddles, from the Polynesian Islands, figs. 64 to 67, all of which must have been derived from a common source. The New Zealand steering-paddle, fig. 64, it will be seen, is simply an elongated celt form. Those from the Marquesas (fig. 65), Society Isles, Fiji, and Solomon Isles, &c, are all allied. In the infancy of the art of navigation, we may suppose that the implements of war, when constructed of wood, may have frequently been used as paddles, or those employed for paddles have been used in the fight, and this may perhaps account for the circumstance that, throughout these regions, the club, sword, and paddle pass into each other by imperceptible gradations. In the Friendly Isles we may notice a still further development of this form into the long wooden spear, specimens of which, from this Institution, are exhibited (figs. 68, 69, and 70).

We must not expect to find all the connecting links in one country or island. We know that the same race has at different times spread over a very wide area; that the Polynesians, New Zealanders, and Malays are all of the same stock, speaking the same or cognate languages. The same race spread to the shores of America on the one side, and to Madagascar on the other, carrying with them their arts and implements, and we may, therefore, naturally expect that the links which are missing in one locality may be supplied in another.

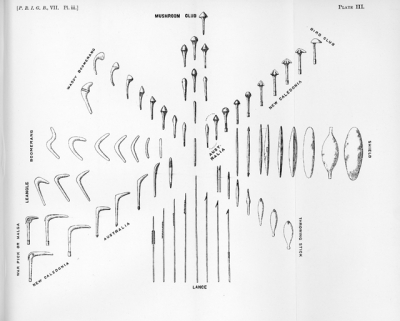

Development of the Australian Boomerang. (Plate XX)

We now turn to the Australians, a race which, being in the lowest stage of cultivation of any with whom we are acquainted, must be regarded as the best representatives of aboriginal man.

I have transferred the Australian sword featured in Plate xix, fig. 61, to Plate XX, fig 72, in order that from it we may be able to trace the development of a weapon supposed by some to be peculiar to this country, but one which in reality has had a very wide range in the earliest stages of culture--I allude to the boomerang. [18]

The Australians, in the manufacture of all their weapons, follow the natural grain of the wood, and this leads them into the adoption of every conceivable curve. The straight sword would by this means at once assume the form of the boomerang, which, it will be seen by the diagram, is constructed of every shade of curve from the straight line to the right angle, the curve invariably following the natural grain of the wood, that is to say, the bend of the piece of a stem or branch out of which the implement was fabricated.

All savage nations are in the habit of throwing their weapons at the enemy. The desire to strike an enemy at a distance, without exposing one's self within the range of his weapons, is one deeply seated in human nature, and requires neither explanation nor comment. Even apes, as I have already noticed, are in the habit of throwing stones. The North American Indian throws his tomahawk; the Indians of the Grand Chako, in South America, throw the 'macana', a kind of club. We learn from the travels of Mr. Blount, [19] in the Levant in 1634, that at that time the Turks, used the mace to throw, as well as for striking. The Kaffirs throw the knob-kerry, as did also the Fidasians of Western Africa. [20] The Fiji Islanders are in the habit of throwing a precisely similar club. The Franks are supposed to have thrown the ‘francisca.’ [21] The New Zealander throws his ‘pattoo-pattoo', and the Australian throws the 'dowak' and the waddy, as well as his boomerang. All these weapons spin of their own accord when thrown from the hand. In practising with the boomerang, it will be found that it does not require that any special movement of rotation should 'be imparted to it, but if thrown with the point first it must inevitably rotate in its flight. The effect of this rotation, it will hardly be necessary to remind those acquainted with the laws of projectiles, is to preserve the axis and plane of rotation parallel to itself, upon the principle of the gyroscope. By this means the thin edge of the weapon would be constantly opposed to the atmosphere in front, whilst the flat sides, if thrown horizontally, would meet the air opposed to it by the action of gravitation the effect, of course, would be to increase the range of the projectile, by facilitating its forward movement, and impeding its fall to the earth. This much, all curved weapons of the boomerang form possess as a common property.

If any large collection of boomerangs from Australia be examined, it will be seen that they vary not only in their curvature, but also in their section; some are much thicker than others, some are of the same breadth throughout, whilst others bulge in the centre; some are heavier than others, some have an additional curve so as to approach the form of an S, some have a slight twist laterally, some have an equal section on both sides, while others are nearly flat on one side and convex on the other.