Three portions of mummy portraits from the Fayoum Egypt: Add. 9455vol2_p573/3

Ruth Allen

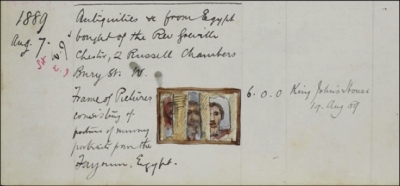

On 7 August 1889, General Pitt Rivers purchased from the Reverend Greville John Chester (1830-1892) for £6 a frame containing “portions of mummy portraits from the Fayoum Egypt”. These were entered on page 573 of the second volume of the catalogue of Pitt Rivers’ ‘Second’ Collection, and deposited at King John’s House. [1] No date is proffered for these portraits, and no precise find-spot recorded; no physical description is given, nor the subjects’ genders specified: only the tiny watercolour illustration loosely records their appearance (Fig. 1). These portraits, therefore, pose several questions that look both forward and backward in their biography: whom do they represent and for what function were they made; where were they found, and how and why did they come into the possession of Chester and through him to Pitt Rivers; and what became of them after 1889?

Pitt Rivers’ catalogue entry notes only that the portraits came from the Fayoum in Egypt. ‘Fayum portraits’ is a term popularly used to describe painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt, dating from the early 1st Century to the late 3rd Century A.D., that have been found in great number – though not exclusively – in the Fayum region. As Taylor has stated, they were the “product of a fusion of two traditions, that of pharaonic Egypt and that of the Classical world”. [2] Combining the style and technique of the latter with the funerary practice and belief of the former, these portraits were made for a specifically local purpose: that of covering the head of the mummified individual represented in the portrait. [3] They were often painted on wooden panels that were inserted over the mummy wrappings, but were also painted on linen shrouds or on plaster heads. Their purpose was to serve as a record of the deceased as they had appeared in life, and as such, individual features and characteristics often appear meticulously observed.

The catalogue illustration shows three fragments of portraits each partially preserving a face against a blue-grey ground: the left-hand fragment is broken in a thin vertical rectangle with angled ends showing only a cross-section of a face with one eye, a nostril, and the edge of a mouth just apparent; the centre fragment is similar in shape, but longer and slightly wider than the first with perpendicular ends, and preserves the centre of the face with both eyes; the right-hand fragment is wider and shorter than both others, with a distinctively-shaped jagged break across the lower edge, and reveals the proper left side of a face, with one large eye, a prominent nose, hair brushed behind the head, and the corner of the right eye just preserved.

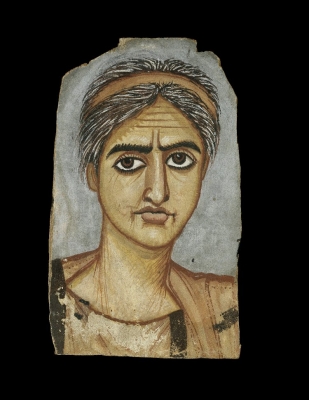

Beyond these details, however, the catalogue does not offer much to identify these portraits further. In order to give more substance to the watercolour images both in terms of appearance and provenance, we may need to look to other catalogued mummy portraits that were excavated at this time. Most of the extant material originates from two main sites: the cemeteries at Hawara, excavated and recorded in 1887-1888 by Flinders Petrie (1853-1942); [4] and the cemeteries at er-Rubayat, unearthed by local inhabitants in 1887, with the majority of finds bought by the Austrian business man, Theodor Graf (1840-1903). [5] We know that Chester regularly wintered abroad in Egypt where he purchased material for the British Museum, the Ashmolean, and the Fitzwilliam Museum. He also regularly offered material to Pitt Rivers, as indicated in his letters to the Salisbury and Wiltshire Museum. [6] The British Museum has a painted mummy portrait of a woman from er-Rubayat, bought in 1890 also from Chester, which may help us partly to reconstruct the provenance and perhaps appearance of at least one of the Pitt Rivers pieces (Fig. 2). [7] Here we see an elderly woman, painted in tempera on wood on a grey ground and dated to the mid-second Century A.D., with greying black hair centrally-parted and brushed around her face towards the back of her head, with a bony, irregular face, and sallow and wrinkled complexion, heavy brows and large eyes with individually indicated lashes. She wears a band of terracotta wool in her hair, and a light terracotta tunic and mantle. A third portrait now in the Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna shows an elderly man of striking similarity of style, colour, and subject-matter to that in the British Museum. [8] Walker and Bierbrier have attributed it to the same artist, further positing that the two portraits may represent members of the same family, perhaps husband and wife, and probably came from the same tomb. [9] This third portrait was bought in Vienna from the dealer B. Kertzmar in 1930, and is known to have been in the Graf collection. [10] It is clear that Chester was purchasing material from er-Rubayat – perhaps directly from Graf, if the British Museum and Kunsthistoriches Museum portraits are related – to be sold to the British Museum in 1890; it seems highly probable that the pieces he sold to Pitt Rivers in 1889 may also have come from er-Rubayat, perhaps even from the same source. Superficially, the composition, colour-palette, and perhaps even the details of the hair-style of the British Museum portrait are similar to those of the right-hand fragment of the Pitt Rivers trio; if we could identify the fragment more accurately, we might be able to confirm this relationship further.

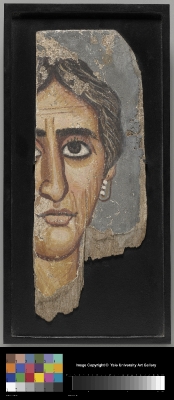

On the 10th December 1984, Sotheby’s London sold a number of items belonging to Mrs. Stella Pitt-Rivers that had formerly been in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Dorset. Included as one lot were three fragments of Fayum portraits, dated in the catalogue to circa 5-6th Century A.D., sadly not illustrated. [11] At least one of the fragments – that of a woman – is published as later being in the collection of Jack Ogden, London, before passing to the London dealer Charles Ede in 1985; it was sold again at Christie’s in New York on the 9th June 2011 for $43,750. [12] The portrait is now in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (Fig. 3). [13] The shape of the fragment and the preserved features of the portrait, together with the colour-palette, are very close to the illustration of the right-hand Pitt Rivers fragment: though we can work only from the watercolour sketch, it seems highly probable from the collection history and physical features that the two portraits are one and the same. The two other fragmentary portraits included in the frame do not match in terms of the shape of the fragment and section of face preserved, while Pitt Rivers’ catalogues record only one other Fayum portrait in his collection, this one clearly male and the panel differently shaped. [14]

The Yale/Pitt Rivers portrait is painted in the tempera technique on wood, probably oak. The dimensions of the panel are 24.5 x 9.5 x 0.4 cm, and it is broken to the left with only two-thirds of the face remaining, also with a jagged break across the bottom edge that deletes the shoulders and bust. Preserved against a blue-grey ground is the portrait of an elderly woman, her age sensitively and realistically portrayed, with wrinkled skin and greying black hair centrally parted and brushed around her face and behind her head. Her heavy eye-brows, hooked nose, large eyes with individually indicated lashes, and sallow, wizened complexion imparts a great sense of individuality; her earring, threaded with three pearls, similarly speaks of the personal whilst also perhaps alluding to her status. Close study of the clothes, hairstyles and jewellery worn by the subjects of these portraits often makes it possible to date them. Although the diagnostic features of this portrait are limited, from her hairstyle it is probable that it dates to the first half of the second Century A.D. The details are close to the British Museum portrait of similar date, while a Roman marble portrait bust of a woman formerly in the Torlonia collection in Rome has hair similarly parted and brushed to the back of the head. [15] CAT scans of complete mummies have revealed a correspondence of age and sex between mummy and image, allowing us to assume a certain level of accuracy of representation here: she appears to us as she did in life and at her death. Some have argued that these mummy portraits were commissioned during the lifetime of the subject, based on the observation that many of the subjects are very young and perhaps in some way, therefore, idealised, but the existence of portraits of elderly subjects such as this must counter that argument, encouraging us to conclude that the portraits were commissioned at death. This portrait is an expressive and sincere representation that does not lie about the age of its subject nor conceal her flaws.

In terms of execution and style, the Yale/Pitt Rivers and British Museum portraits are distinctly alike: the hair and wrinkles around the women’s mouths, between the eyes and across the brows are similarly articulated, as are the wrinkles across the neck, and the use of a thick brown line to mark the outline of the face and features. The colour palette is also similar, although the Pitt Rivers example has more depth of colour and tone. It is tempting to relate the subjects in the manner of the British Museum and Kunsthistoriches Museum examples (Sisters? Cousins?); however, it is most likely that both portraits are related by coincidence of date, subject-matter, and find-location: several painted mummy portraits from er-Rubayat show older women with the same distinctive hair-style, facial features, and similar jewellery. [16] Moreover, the mummy portraits found in the cemeteries at er-Rubayat are almost exclusively executed using the tempera technique – those found at Hawara use encaustic – which explains to some extent the similarity of colour, tone and technique between the two portraits. [17]

As with the majority of extant mummy portraits, the Yale/Pitt Rivers example does not identify its subject by name. If we assume that the other two fragments in Pitt Rivers’ frame also originated from er-Rubayat, fixing a find-spot does, at least, allow us to infer some details about all three subjects. It has long been thought that the cemetery at er-Rubayat was for the residents of Philadelphia, but it seems likely that it in fact served another settlement at Mansura. [18] We can assume that our portraits depict members of the local elite, as only a small percentage of those who could afford mummification could also commission a portrait. [19] We can also glean something of their cultural identity. The people of the Fayum were a cultural mix: descendents of the Greek mercenaries who had fought under Alexander and settled in the area, marrying local women and adopting Egyptian beliefs. Many mummy portraits reflect an interest in Greek culture: the men are often bearded, the youths suntanned, alluding to an education in the gymnasium; one famous portrait of a young woman gives her name and profession as Hermione grammatike, highlighting her status as one of the grammatikai, upholders of Greek cultural traditions within the framework of Roman rule. [20]

More than just a representation of a social demographic, however, Pitt Rivers’ framed mummy portraits – and that of the old woman as main example – represent a final poignant glimpse of a deceased life. They stand as testaments, recording the appearance of the long dead and evidencing their existence: they are defiant with their honestly observed features and quiet, sombre expressions. Where the artists and subjects aimed for immortality through the physical act of recording an appearance, the afterlife of these three portraits themselves has followed a perhaps unforeseen route. Excavated, traded, bought, sold, and displayed, the portraits have shape-shifted over time and can be considered in different guises: perhaps for Graf, Chester, and the local excavators at er-Rubayat, they represented buried treasure and a business opportunity; for Pitt Rivers, the prolific collector, further example of the technical development of mankind; [21] for Sotheby’s and Christie’s, valuable artworks; and now for Yale, the single female portrait represents an object acquired as a historical and didactic source, part of the gallery’s mission to encourage appreciation and understanding of art and its role in society. [22] Though currently not on view, the portrait has nevertheless also maintained its original function through these accrued layers of additional status: the memory of its subject persists, if anonymously. And it is thanks to Pitt Rivers’ original acquisition that this one of many “portions of mummy portraits from the Fayoum Egypt” has survived for us to think about, illustrating the personal and performative function of this art form as a means of recording, expressing, and confirming identity.

Notes

[1] Add. 9455vol2_p573/3.

[2] Taylor 1997, p. 9.

[3] Walker 1997, p. 14.

[4] See, for example, Petrie 1913

[5] For the catalogue of Graf’s collection, see F. H. Richter and F. von Ostini 1900.

[6] Letters L221 (11 June 1886), L386 (24 Aug 1887), L487 (7 May 1888), L2281 (29 May 1886), L2531 (undated).

[7] BM 1890,0921.1 (Painting 87). See also Walker and Bierbrier, p. 89, no. 79.

[8] Vienna, Kunsthistoriches Museum X300. See also Walker and Bierbrier, p. 88, no. 78.

[9] Walker and Bierbrier 1997, p. 90.

[10] Walker and Bierbrier 1997, p. 89.

[11] Anonymous sale; Sotheby’s, London, 10 December 1984, lot 154.

[12] Anonymous sale; Christie’s, New York, 9 June 2011, lot 66.

[13] Ruth Elizabeth White Fund, 2011.102.1. See also Parlasca and Frenz 2003, Bd. 4, p. 82, no. 856, fig. 8, tav. 184.

[14] Add.9455vol2_p444/11; acquired from Flinders Petrie in 1888.

[15] See Borg 1996, no. 84,2 and 3.

[16] There are examples in the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge; the St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis; and the Pushkin Museum, Moscow: for images, see Borg 1996, no. 48,2; no. 48,1; and no. 84,1.

[17] Doxiadis 1997, p. 21.

[18] Walker and Bierbrier 1997, p. 86.

[19] Bagnall 1997, p. 17.

[20] Walker 1997, p. 16.

[21] Rethinking Pitt-Rivers | Home http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/rpr/

[22] http://artgallery.yale.edu/pages/info/director_mission.php

Bibliography

Bagnall, R. S., ‘The Fayum and its People’, in Walker, S. and Bierbrier, M. eds, Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, London, 1997, pp. 17-20.

Borg, B., Mumienporträt: Chronologie und kultureller Kontext, Mainz am Rhein, 1996.

Christie’s, Anonymous sale, New York, 9th June 2011.

Doxiadis, E., in Walker, S. and Bierbrier, M. eds, Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, London, 1997, pp. 21-22.

Flinders Petrie, W. M., The Hawara Portfolio: Paintings of the Roman Age, London, 1913.

Richter, F. H. and von Ostini, F., Catalogue of the Theodor Graf collection of unique ancient Greek portraits, 2000 years old, Vienna, 1990.

Taylor, J., ‘Before the Portraits: Burial Practice in Pharaonic Egypt’, in Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, London, 1997, pp. 9-13.

Sotheby’s, Anonymous sale, London, 10th December 1984.

Walker, S. and Bierbrier, M. eds, Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, London, 1997.

Walker, S., ‘Mummy Portraits and Roman Portraiture’, in Walker, S. and Bierbrier, M. eds, Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt, London, 1997, pp. 14-16.

May 2012.