Five Mexican Pots

Are We Potty? 5 Lonesome Pots Try 5Y Analysis

Introduction to 5Y analysis

* “The 5 Whys is a simple but powerful tool to use with any problem. It's a technique to help you get past the symptoms and find root causes. First form a team. Then ask each other the question "why" up to five times.” (www.the-happy-manager.com)

* “The team goal is to work backwards from the result to the cause, with each question revealing more and more… Start with a simple problem statement about what the issue is …” (www.ehow.com)

Problem Solving Team – Names, Brief Descriptions & Contact Details

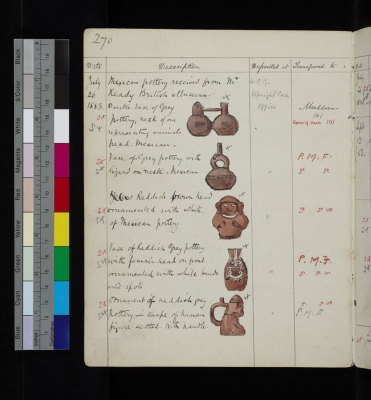

* Members: Double Pot, Pot, Head, Pot, Seated Human Figure Pot.

* Identifying Characteristics: “double vase of grey pottery, neck of one representing animal’s head; vase of grey pottery with lizard on neck; reddish brown head ornamented with white; vase of reddish grey pottery with female head on front ornamented with white bands and spots; ornament of reddish grey pottery, in shape of human figure seated, with handle.”

* ID: all noted in database as “Mexican”.

* Contact: Pitt-Rivers' second collection catalogue Vol 1, page 270, at Cambridge University Library [Add.9455vol1_p270].

Team Statement of Problem

* The issue is our failure to communicate with the humans with whom we share our exile. Our émigré names demonstrate that we command little status and less understanding. Though the humans manage “Figure” and “Vessel” as well as “Pottery” as key words, two of us rate no more than “Pot”. Only one, “Head”, merits a more meaningful title. Our identifying characteristics add very little. We need to do better, if only to gain respect for our age. This, at least, the humans appreciate: they have us down as A for Archaeological, not E for Ethnographic. We may even be Pre-Columban. That’s about as far as it goes. Otherwise, in the hundred plus years since 1883, they haven’t found out anything other than our nationality. We need to change the situation, find a role for ourselves.

* As long as we are in exile, our duty is to be cultural ambassadors. We owe it to ourselves to stand up for Mexico. We could say to our hosts, to paraphrase their national bard, “Friends, there is more to our country than is known in your philosophy.” Our homeland is not only huge – a surprise to first-time visitors - but has multiple regions, ethnicities and faiths. Historically we could mention the Olmec, Maya and Aztec civilisations – all pre-Columban. Mix in five centuries of Spain and the Catholic Church and you have a recipe for staggering ethnic, cultural and religious profusion. Mexico is a fabulous mix of ancient and modern, Christian and pagan – and we Mexicans reinvent ourselves every day. Our history and culture are alive and well, despite the influence of the Yankees across the Rio Grande. Just look at customs like our Day of the Dead.

* If only we could persuade British tourists to leave their margaritas on the beach at Cancun, they’d taste excitement and adventure beyond their wildest dreams. Mexican history poses more mysterious questions than a Hollywood fantasy. For example, who were the original builders of Teotihuacan? And that’s just to mention a place within easy reach of a Mexico City hotel – a taxi will take you from the doorstep. That is if you can get a price out of the driver for which you don’t need to win the lottery.

* How can we give British visitors the urge to scrap the package holiday and venture further? We need to find a way for them to experience the revelations, to European eyes, of setting foot in the kind of places where we may well have been found: for example, the fabulous Olmec and Mayan sites of Chiapas Province or Ruta Puuc in Yucatan. If they are bored by palaces and pyramids, they can always come up to date and visit, say, Real de Catorce, the ghost town in the hills of the Sierra Madre Oriental where “The Mexican” was filmed.

* Unfortunately our hosts have no idea which region, ethnic group or culture we hail from. They don’t know who made us, what for or by what process. They don’t even seem to have a note of our dimensions. To regain our self-respect, we have to awaken their curiosity.

Why, Why, Why, Why & Why?

* Head: Just because I’m the one with a title other than Pot, my colleagues have elected me leader. I’ll start the ball rolling by playing devil’s advocate. Why do our hosts not know more about us? Dare I say it’s because they haven’t had the impetus to find out? Since the nice Pitt-Rivers people received us from Mr Ready, the British Museum’s “renovator”, in 1883, they have looked after us and respected our privacy. But as far as getting to know us is concerned, we have suffered a hundred plus years of courteous neglect. Ready or not, I have to pose our Number One Question.

* Double Pot: As a pot with above average capacity, Head has appointed me deputy. “Two heads are better than one”, he quipped. I make it three, actually, skip. I think you answered your own question when you said our hosts have not had the impetus. This laissez-faire attitude has pandered to the average Brit’s lack of interest, knowledge and understanding of the world beyond familiar boundaries. What does being old and Mexican mean to your typical Pitt Rivers punter? When mum and dad bring the kids for a wander round the museum, what would they make of us, if only we were on show? Do we represent anything of value? OK, we’re not exactly spectacular looking. There are other Mexican historical characters who’d make more of an impression. None of us is exactly Quetzalcotl, the plumed serpent. Nevertheless a small clay “vessel” can hold three kinds of value: aesthetic, practical or, how shall I put it, imaginative and symbolic. By that I’m referring to the religious and spiritual aspects of life, or, in our case, I suspect, death. Who knows what desires, hopes and dreams went with us into the graves from which we were plucked? For what else does A for Archaeological usually imply? Check the auction websites – clay votive figures, with a certificate of authenticity from some funerary site, fetch thousands. So would your average punter find us beautiful? Would they think we had been of any use in our homeland? Would they feel anything of our spiritual or ritual significance? No, no and no. Why not? This is Question Number Two.

* Seated Human Figure Pot: Thanks a bunch – just because our hosts have noticed I’m “seated” I’ve got the secretary’s job…I hope it’s not my other prominent feature. You two big-heads mustn’t look to me to get a handle on things. Hang on, let me minute what Double Pot said – it sounds important. In answer to his question, I reckon it’s because the Brits’ ideas about what is beautiful, useful and spiritual come from pottery made in places they know: parts of the world where they trace their own roots plus others where their ilk have been over the centuries. I’m talking, first, about Ancient Greece and Rome and, second, the lands which the British have plundered and/or colonised. Let’s look at what they call beautiful. If they’re honest, they will admit that Greek and Roman ceramics set their aesthetic standards. It’s true in pottery as in so many other fields. Why else do they call everything about Graeco-Roman civilization “classical”? As for what turns them on from elsewhere, the pottery of, say, China or West Africa has moulded their concept of beauty to be found in the other, the exotic. Against a single Grecian urn or Ming vase, five ancient Mexican pots just don’t match up. Why? If you ask me, it’s because the Brits neither trace their identity to, nor conquered, Mexico. So Question Number Three is why did we get collected in the first place? If we can dig down to that, we might find what will get our hosts going. This new lot sound enthusiastic. “Rethinking Pitt Rivers”, eh? Let’s give ’em a hand. Let’s go back to basics.

* Pot: We know we came from the British Museum. Sounds like the Pitt Rivers people thought they could look after us better. I wonder if it was the big cheese’s decision? PR himself, or one of his agents? We must have had something about us, or was it just for completeness’ sake – those Victorian gentlemen anthropologists liked to have comprehensive collections. So what happened? Why have we not turned that initial curiosity, concern for our well-being or, dare I say, mere lust for ownership, into further enquiries? Why have we inspired no investigations, no field trips, no documentary research? There’s Question Number Four

* Pot: I reckon they don’t know where to start. Enough of macho sob-stories! If only this, if only that…If you lot were British men, you’d be crying in your beer… I’m the only woman, so I’ll take a lead. We must accentuate the positive. To do them justice, the PR people have noticed my markings. Their database says I’m “ornamented with white bands and spots”. Now Google may be a gringo invention, but it has its uses... I’ve checked out the British Museum website, since the BM is where we lived when we were first transported to this miserable, drizzly island. The BM has modern pottery, collected by Chloe Sayer and Marcos Ortiz, with markings like mine. “Painted with white accents” says its database, about a donkey figurine from Acatlan, in the Puebla region, east of Mexico City. There’s a water jug as well. Both are burnished with a kind of glaze called “orange slip”. Given that we are a lot older, could my “reddish grey” colour, I wondered, once upon a time have been similar? Mr Secretary, you too are described as “reddish grey”. You, Boss, are “reddish brown ornamented with white”. Although it was a tenuous lead, I followed up on Acatlan pottery. I found out that there may be a connexion. The foot-turned parador, a mobile support for making pots in modern Acatlan, is very similar to the kabal of the Maya village of Mama, in Yucatan, where there is little Spanish influence. An American archaeologist suggests that the technique may be ancient. There is evidence that something similar was known and used in pre-Columban times by the Olmecs of La Venta, a place approximately halfway between Acatlan and Mama. He also complains about the lack of communication between archaeologists and ethnographers, which stands in the way of horizon-broadening work like his. Ah well! Instead of getting hung up on another piece of male moaning, I went in search of Ms Sayer’s wonderful book, “Arts and Crafts of Mexico”. She writes with respect and affection about the likes of us: “Mexican ceramics range, as they did before the Conquest, from simple elegance to profuse ornamentation…” Mexican potters, “often using the simplest of tools and relying on instinct rather than science, have one thing in common: their creations, whether functional, ceremonial or purely decorative, are all worked with loving care.” Chloe Sayer is all right with me. She illustrates her chapter on modern Mexican pottery with photographs of a number of pots not a million miles in looks from us. As well as the products of Acatlan, my eye was drawn by others: hand-modelled clay animals from the Lacandon community of Naja, in Chiapas; a duck-shaped vase from Ocotlan, Tlaxcala; an earth-coloured clay figure from Santa Maria Tetecla, Veracruz. Then I spotted a small vase from the Tzeltal village of Amatenango del Valle, in Chiapas, fired without a kiln, in traditional style, and painted with earth colours. You, my friend Pot, have a lizard on your neck. This little number has two! Look, we may be ancient, but, in our own country, it looks like, gee, we may have made a mark! Posterity has not forgotten us. Perhaps not only our Pre-Columban looks, but also the way we are made inspires potters today. So why be sad? How about that for Question Five? Let’s find reasons to be cheerful.

* Head: Thanks, sis. It’s down to me to sum up. Looking on the bright side, our starting point can be that we’re out of sight but not out of mind, gone but not forgotten. If we went back to Mexico today, we’d be recognised. So my plan is to take pride in ourselves where we are. Let’s not be hung up on the past. Whoever brought us to Britain was at least looking outward. In 1883, when the Pitt-Rivers took us on, our appearance must have seemed very odd. European artists had not yet turned on to “Primitive Art”. Picasso, born in 1881, was a terrible two, Modigliani only a twinkle in his mother’s eye (he appeared in 1884). Gauguin was still trying to make it as a businessman – he didn’t go to Martinique till 1887. So c’mon, pucker up, let’s put on our best faces. Maybe some enterprising person will take up our case. There is one place where they might track down who we are: the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Speaking of famous artists, did you know there is a whole room devoted to Diego Rivera’s collection of pre-Columban pottery? We’d be totally at home. Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo are Mexico’s best known artists. They loved the likes of us. Their house was packed with tubby little figures. Rivera was not only a father of the modern Mexican nation, but a big fan. There’s a lovely photo, on the wall at the museum, of him surrounded by his collection. Diego identified strongly with us – maybe also because he was physically not dissimilar! We are tangible links with the pre-Christian past. Our brothers and sisters inspired Rivera and Kahlo’s paintings and politics. The best case scenario for our future, I propose, is to get sent back to the National Museum of Anthropology, if only on a visit for ID purposes. In the meantime, we have a role to play. Viva La Cultura Mexicana!

Richard Gray, February 2011.

References

Acatlan Pottery in the British Museum: 1970s donkey figurine & water jug, AN5425001 & AN172803001, collected by Chloe Sayer & Marcos Ortiz, previously exhibited at Horniman Museum, 1977-8.

Foster, George M. 1960 'Archaeological Implications of the Modern Pottery of Acatlan, Puebla, Mexico', American Antiquity (Journal of the Society for American Archaeology) 1960

Sayer, Chloe. 1990 Arts and Crafts of Mexico, London: Thames & Hudson Ch IV.

Acknowledgement: thanks to Corinna Gray MA (Intern at Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford) for her support and encouragement - anthropological, linguistic and personal; and the Rethinking Pitt-Rivers project team for the opportunity to contribute.

Note:

When the pots refer to Pitt Rivers, they mean the man, Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers or his museum, the Pitt-Rivers Museum at Farnham, Dorset (they are not always clear about this, presumably no-one ever took the time to explain to them). Their current whereabouts are unknown, it is quite possible that they were sold off during the 1960s and 1970s by Stella Pitt-Rivers and could now be anywhere in the world, gracing a museum or a private collection with their presence, they may even be back in Mexico! [AP, February 2011]

![Rivera and pots [photo of photo taken by the author, Richard Gray]](../../../component/joomgallery/image/index-view=image&format=raw&type=img&id=582&Itemid=41.html)