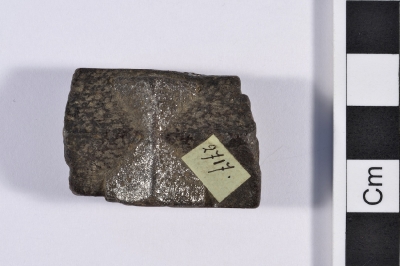

Staurolite crystals from Auray, Brittany, France. 1884.56.5, 1884.56.6, 1884.56.7

Rosanna Blakeley, Cataloguing Assistant, Small Blessings Project (Feb-Sep 2012, Pitt Rivers Museum.

The primary documentation for three staurolite crystals in Lt. General Pitt-Rivers’ founding collection is as follows:

Accession Book IV entry - 1884.56.1 - 100 Charms Magic etc. - Specimen of staurolite, regarded by Bretons as of supernatural origin and to have supernatural powers Auray Brittany 33/ 9029

Delivery Catalogue II entry - Religious emblems 3 specimens of staurolite 33/ 9029 13 Cases 225 226

'Green book' entry - South Kensington Receipts, 27 February 1879 - 2 crystals in form of crosses or 'Green book' entry - South Kensington Receipts, 1 August 1879 - 'A crystal staurolite'

These three staurolite crystals were originally displayed at the South Kensington Museum in London (now known as the V&A) in 1879 before coming to the Pitt Rivers in 1884. They are currently on display in the court in Case 61.A in the same box, with a label that reads: ‘Staurolites (‘Pierres de la Vraie croix’), found in the soil in the neighbourhood of AURAY, BRITTANY, believed to be of supernatural origin & to have magic virtues. P.R. coll. [33/9029].’

Staurolite is a mineral consisting of basic aluminium and ferrous iron silicate. One of the properties of staurolite is that well-formed crystals are commonly twinned and appear cross-shaped, either at 90 or 60 degree angle. The name staurolite is derived from the Greek stauros meaning cross and lithos meaning stone. Hence, staurolite crystals are known as ‘cross stones’.

Staurolite is commonly found in the Brittany region of France, and it is possible that Pitt Rivers collected these examples during one of his visits to Brittany in October-November 1878 and March-April 1879. Other well-known locations where staurolite is found are The Blue Ridge Mountains and Fairy Stone State Park in Virginia. The name of Fairy Stone Park makes reference to several other terms for staurolite crystals - ‘Fairy Stones’, ‘Fairy Crosses’ or ‘Fairy Tears’.

The accession book entry for these objects states that Bretons believed staurolite crystals had ‘supernatural origins’ and ‘supernatural powers’. There are several similar examples in the Adrien de Mortillet (1853-1931) amulet collection, also from Brittany, which were collected sometime before de Mortillet’s death. One of them is shown on the second photograph on this page, which was collected by him in Brittany before 1931 and was donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum by the Wellcome Institute in 1985 (1985.52.1328). de Mortillet notes in his catalogue that staurolite crystals were still being used as amulets. The examples in these collections point to a history of staurolite crystals being considered amulets.

So how did these staurolite crystals acquire associations with fairies? Duffin and Davidson throw light on this in their article ‘Geology and the Dark Side’ [2011]. In this article they examine the ‘diabolical and supernatural folklore traditions of geology’ [p.7] based on the ‘vernacular terminology’ [p.8] used in reference to various stones and fossils.

According to Duffin and Davidson fairies have commonly been linked to crystals and fossils in European folklore traditions. However, fairies had more negative connotations in the past than they do today. Fairies were

commonly held responsible for the sudden, otherwise inexplicable onset of illness in humans and livestock, to cause profound meteorological changes adverse to farming practices, to upset the fertility of the fields and to harbour an unhealthy interest in children whom they might kidnap or otherwise cause harm to. [p.10]

Duffin and Davidson also suggest that there is a variety of folklore associating fairies with crystals and fossils because people were believed that they lived underground.

Duffin and Davidson specifically mention ‘Fairy Crosses’ from the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. This name may have been given to twinned staurolite crystals due to the migration of fairy folklore with Irish settlers to the USA in the mid-nineteenth century. The term ‘Fairy Tears’ refers specifically to another explanation that twinned staurolite crystals are the petrified tears shed by fairies when they heard of Christ's crucifixion. The combination of both Christianity and folklore is interesting in this particular story behind staurolites.

The American mineralogist George Frederick Kunz (1856–1932) also provides information on the use of staurolite crystals in North American culture. In his book The Magic of Jewels and Charms [1915] Kunz traces the ‘popular fancy’ for ‘Fairy Stones’ in North America back to the Trail of the Lonesome Pine [1908] written by John Fox, Jr. Kunz explains that Fox ‘makes one of these pretty staurolite crystals exercise an important influence over the destinies of his hero and heroine’ [p.37]. He then goes on to recount that subsequently the manager of a New York theatre ‘cleverly utilized’ this aspect of the book when he put on a dramatization of the Trail of the Lonesome Pine. The manager gave a ‘Fairy Stone’ to every woman in the audience, ‘few of whom were not unconsciously influenced by the symbolic half-religious, half-mythical quality ascribed to this attractive little gem’ [p.37].

The importance of staurolite crystals as amulets, especially in North America, is also highlighted in Dunwich’s Guide to Gemstone Sorcery [2003]. Gerina Dunwich is a professional astrologer, occult historian, and New Age author. She claims that United States presidents Roosevelt, Harding, and Wilson all carried a staurolite for good luck [p. 83]. Dunwich also says that in some places it has been common to give children staurolite ‘to wear about their necks or carry in their pockets to keep them safe from wicked spells and the power of the evil eye’ [p. 83].

So staurolite crystals have been considered to be fairies tears, good luck charms, and in some cases have been used to protect children from evil spirits. They continue to have folklore and supernatural associations today. A basic Internet search brings up websites that list staurolite crystals as ‘powerful crystals’. There is also a website for a holiday cottage claims that the ‘surrounding fields are world famous for producing naturally occurring "cross stones". These are as the name suggests, stones in the form of a cross said to bring good luck to the bearer!’ [1]

It is impossible to say exactly why Pitt Rivers’ chose to collect these staurolite crystals, but perhaps he was interested in how natural objects acquire folklore and supernatural associations. Further, these objects are from Europe and perhaps their contemporary use as amulets intrigued a scientific man like Pitt Rivers.

References / Further Reading

Duffin & Davidson. 2011. ‘Geology and the Dark Side’ in Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, Vol. 122, Issue 1, pp. 7-15

Dunwich. 2003. Dunwich’s Guide to Gemstone Sorcery. Career Press.

John Fox, Jr. 1908. Trail of the Lonesome Pine. London: Constable & Company.

G F Kunz. 1915. The Magic of Jewels and Charms. Philadelphia & London: J.B. Lippincott.

Notes

[1] http://www.gite-brittany.org/phdi/p1.nsf/supppages/1527?opendocument&part=2

July 2012.

![Staurolite on display in Case 61.a in the court [1884.56.5-7]](../../../component/joomgallery/image/index-view=image&format=raw&type=img&id=1193&Itemid=41.html)