Objects that are said to be part of Pitt-Rivers' second collection,

but cannot be found in the catalogue held by Cambridge University Library

Part I

Introduction

Below is information about several artefacts that have been identified as being from the second collection but cannot be matched by the project researcher to entries in the catalogue held by Cambridge University Library [CUL]. It is not clear, at this time, what this means but it could mean several things:

- The researcher has made an error and the object is entered in the CUL catalogue.

- Information now attached to the object does not match the information provided by the catalogue, making a match difficult

- The object is not entered in the catalogue because it was acquired by the Pitt-Rivers family after 1900 when entries cease.

- Some of the objects acquired by Augustus Pitt-Rivers between 1880-1900 were not entered in the catalogue (to date there is little firm evidence of this, though this page might prove evidence of it, if secondary proof can be obtained)

- The items might have been acquired before 1880 and not formed part of the founding collection, but retained as part of the Pitt-Rivers’ private collection and later subsumed within the second collection. This would mean that they would not appear in the CUL catalogue, because these entries do not start until after 1880, but nor would much documentation exist for them before 1880, when documentation was much sketchier. See here for more information about the documentation of both collections. To date there is no evidence which has allowed any objects to be clearly identified as such.

We are interested in these items for what they might show us about what the catalogue of the second collection actually was:

- Was it a comprehensive catalogue containing details of all the objects acquired between 1880-1900? (It is fairly clear that it was not. While many of the items listed below may have been acquired by Pitt-Rivers, there are some which were definitely acquired by him between 1880-1900, and should therefore have been included in the catalogue, but appear to have been omitted.)

- Were items acquired by Pitt-Rivers' descendants and added to the Farnham Museum displays? If they were, and they were of a similar nature to the items listed in the catalogue held by Cambridge University Library, might they later get confused with Pitt-Rivers' original second collection and come to be associated with the General's collection?

- Did Pitt-Rivers himself retain some items acquired before 1880 which might have formed part of the founding collection and which were of a similar nature? If he did, these would not have been recorded in the catalogue of the second collection, and the poor documentation of the founding collection means that it is not possible to be certain if there were such items.

- Were some categories of objects which were acquired by Pitt-Rivers between 1880-1900 not recorded at all, or only partially, in the catalogue of the second collection? (The answer to this seems to be a tentative 'Yes'. There are certainly some fine art and objets d'art which appear not to have been listed but definitely acquired during this time. The picture is very confused, however, because some items of this nature are recorded therein throughout the period).

- The final option might be - were some items so poorly described, or wrongly ascribed, that it is now impossible to find them if you know what the objects actually might be, or might be from?

An item that was in the second collection of Pitt-Rivers':

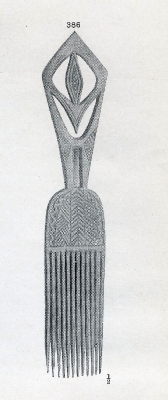

This item is not an alleged artefact of Pitt-Rivers but a definite one because it is included in his privately published book 'Antique Works of Art from Benin' as figure 386 described as 'Wooden comb, with carved design' and was therefore definitely owned by him by 1900. Nevertheless this cannot be found in the catalogue of the second collection held by Cambridge University Library. It seems strange that he should document it in the book, but not in the catalogue; the reason for this is unknown.

An item possibly collected by George Pitt-Rivers:

At an auction at Christie's, Amsterdam, on 24 May 2000 some secret-sacred material was sold from Australia, described as 'a pair of Australian aborigine feather shoes and a pointing bone for Kurdaitche [sic] The first of woven fibre and feathers, the bone of drop form pierced at the tip 21cm. and 8cm. long Provenance Capt. George Pitt Rivers The pointing bone has a label inscribed: Pointing-Bone used on a Kurdaitche [sic] or mythical killing expedition. It is pointed at the enemy from a distance, & he is then supposed to fall senseless to the ground; his vital organs are then removed & he is sewn up, & returns to his camp & kin, unconcious of what has befallen him, gradually droops & dies, unless he can get the aid of a medicine man & find out his enemy. Central Australia'.Pitt-Rivers himself did not obtain any items like this for the second collection, though similar items are part of the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. These include two objects donated by W.A. Horn in 1897, which were collected during the Horn Scientific Exploring Expedition, also notable because it was the occasion when the two eminent Australian anthropologists Walter Baldwin Spencer and Frances James Gillen met. One reason why Pitt-Rivers himself might not have acquired many artefacts like this is that the area where they were produced, by the Arrernte around Alice Springs in the Northern Territory, only had significant European populations from the early 1890s and therefore few such pieces probably made it onto the London art market before he died.

Artefacts that might well form part of Pitt-Rivers' second collection but do not seem to be listed in the catalogue

Many items which come up for sale at auction houses, are owned by members of the public, or appear in public museum collections, purport to come from the Pitt-Rivers collection. Some of these objects cannot be matched to objects listed in the catalogue of Pitt-Rivers’ second collection, held in the Cambridge University Library (accessible via the Databases section on the menu to the right of this page)

1. The first object is listed in the collections of the Barbier-Mueller Museum in Geneva. It bears similarities with many of the chalk figures listed in the second collection catalogue, but does not appear to precisely match any of them judging by physical appearance between the photographs and the drawings in the catalogue. It has an accession number of 4317-B at the museum, and their website gives the following details:

Kulap. Melanesia. Papua New Guinea Bismarck Archipelago, New Ireland southern region. 19th century. Chalk H: 75 cm Formerly Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, Farnham sold by W.D. Webster before 1900. Collected circa 1890. INV. 4713-B Recent field research indicates that the carved stone figure traditions of central New Ireland are more complex than was previously understood .... The earliest information that we know regarding these chalk figures was recorded by Rev. George Brown when he visited the Hinsal-speaking region in the west cost Patpatar area of southern New Ireland ...

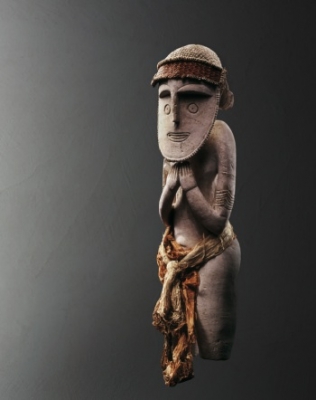

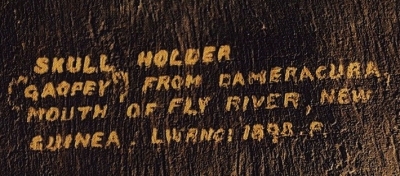

2. The next item is also held by the Barbier-Mueller Museum in Geneva. There are two images below of the object and its label (attached to the back); the object is described as a skull rack from Papua New Guinea. This object cannot be matched to the items listed in the catalogue of the second collection, but the information on the label seems to make it clear that it must have formed part of Pitt-Rivers’ collections.

3. The Metropolitan Museum has an artefact, with its accession number, 1979.206.75, an Asanta wood figure from Ghana. The information they provide about this figure is as follows:

Fertility Figure: Female (Akua Ba); 19th–20th century; Asante, Akan,Ghana; Wood, beads, string; H. 10 11/16 x W. 3 13/16 x D. 1 9/16 in. (27.2 x 9.7 x 3.9 cm); Provenance: Augustus Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers; [Everett Rassiga, New York, 1957]; [Merton D. Simpson, New York, February 1969]; Nelson A. Rockefeller, New York, on permanent loan to the Museum of Primitive Art, 1969-1978. Description: Disk-headed akuaba figures remain one of the most recognizable forms in African art. Akua ba are used in a variety of contexts; primarily, however, they are consecrated by priests and carried by women who hope to conceive a child. The flat, disklike head is a strongly exaggerated convention of the Akan ideal of beauty: a high, oval forehead, slightly flattened in actual practice by gentle modeling of an infant's soft cranial bones. The flattened shape of the sculpture also serves a practical purpose, since women carry the figures against their backs wrapped in their skirt, evoking the manner that infants are carried. The rings on the figure's neck are a standard convention for rolls of fat, a sign of beauty, health, and prosperity in Akan culture. The delicate mouth of the figure is small and set low on the face. The small scars just discernible below the eyes of this figure refer to a local medical practice as protection against convulsions. Most akua ba have abstracted horizontal arms and a cylindrical torso with simple indications of the breasts and navel; the torso ends in a base as opposed to human legs. The style of this sculpture is rare among other extant examples of akua ba due to its miniaturized naturalistic body, arms, and legs. Full-bodied figures such as this are believed to be a recent twentieth-century innovation within the akua ba sculptural tradition. The name akua ba comes from the Akan legend of a woman named Akua who was barren, but like all Akan women, she desired most of all to bear children. She consulted a priest who instructed her to commi ssion the carving of a small wooden child and to carry the surrogate child on her back as if it were real. Akua cared for the figure as she would a living baby, even giving it gifts of beads and other trinkets. She was laughed at and teased by fellow villagers, who began to call the wooden figure Akua ba, or "Akua's child." Eventually though, Akua conceived a child and gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. Soon thereafter, even her detractors began adopting the same practice to overcome barrenness. All genuine akua ba are female images, primarily because Akua's first child was a girl but also because Akan society is matrilineal, so women prefer female children who will perpetuate the family line. Girls will also assist in all household chores, including the care of any smaller children in the family. After influencing pregnancy, akua ba are often returned to shrines as offerings to the spirits who responded to the appeals for a child. A collection of figures becomes an advertisement for the spirits' ability to help women conceive. Families also keep akua ba as memorials to a child or children. The figures become family heirlooms and are appreciated not for their spiritual associations, but rather because they are beautiful images that call to mind a loved one.

None of the African figures in the second catalogue match this fertility figure,. The sale record of the figure is not clear, there does not seem to be any record of where it was sold in the UK, it may have been sold to a US dealer directly.

4. The catalogue for Sotheby’s sale 14.7.1975, in which the Ancient Egyptian stele listed above was sold, lists four other items which appear to be from the Pitt-Rivers collection. While these objects are not listed in the catalogue of Pitt-Rivers’ second collection, the catalogue does not say they are from anyone else or from unnamed sources. Because of the ambiguity of the catalogue, it may be that these were never part of the second collection. However, the source (Flinders Petrie) is one associated with many objects in that collection, and the writing on the objects (shown clearly in the photographs; all the objects are illustrated), appears to be similar to that used on objects in the second collection. As discussed here, however, other museums and private collectors used similar documentation methods.

Lot 119 An Egyptian Mummy wrapped in mummy cartonnage, linen and fibre strips, the front with s mall gilded roundels under the wrapping, the front of the head originally with a mummy portrait, (now missing) approximately 44 1/2 in (173 cm) Ptolemaic Period

Lot 120 An Egyptian cartonnage mummy mask with vivid blue, white, red and green-painted decoration, with winged cobras and a scaraboid on the head, mounted on a fibre-bound wooden frame in the form of a mummy and overlaid with the original white linen mummy wrappings covered in polychrome cartonnage ornaments comprising two winged cobras to either side of a beaded collar surmounted by a winged scarab, two figures of a Goddess flanking a winged figure of Isis, and other divinities below flanking decorative pectoral emblems, the foot with mummy cartonnage feet 66 1/2 in. (168.9 cm) Ptolemaic Period The stand with an inscription reading "Cartonnage, head and figures mounted on cloth, Ptolemaic Period BC 332-330, from Gurob, Illahun, Fayum, Egypt, found by Mr Flinders Petrie.

Lot 121 The Upper Part of an Egyptian wood sarcophagus, in the form of a head and shoulders of a male figure wearing a white, blue and pink-striped wig, the hands in relief, the face and hands white, with blue and black details, the body black, 30 in (76.2 cm) by 22 in (56 cm) approximately Late Period, from Illahun, Fayum, found by Mr Flinders Petrie in 1888. [The illustration shows that this object is labelled 'Bust of hard wood from coffin XXth - XXVI th dynasties BX 1200-528 From Illahun, Fayum, Egypt. Found by Mr Flinders Petrie in 1888].

Lot 122 An Egyptian cartonnage mummy mask, with gilded face, blue tripartite wig decorated with a gilded scaraboid and wearing an elaborate collar, the pupils of the eyes black 18 3/4 in (47.6 cm) c 1st century AD, Roman Period from Hawara found by Mr Flinders Petrie. [The illustration shows that the object is labelled 'Gilt stucco head Roman 1st cent. AD from Hawara, Egypt Petrie'.

5. There are 3 gold ornaments in the Dept of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum that was clearly purchased at the Egger sale, Lot 113 and 114 but it is not recorded where we would expect it to be in volume 3 around page 747. Here is the information about them:

BM 1974,1201.343 Gold brooch. The brooch was made from a gold wire which begins with a large spiral terminal which then continues into a twisted wire body. At the end of the body is the hinge of the brooch where the wire straightens and is then tightly coiled before being bent back to form the pin of the brooch. Along the twisted wire body are four sets of two spirals attached by strips. The clasp is a straight loop that is the link between the large spiral and the twisted wire body. Romania,Timiş (county),Timişoara,Temesvár) 1600 - 1200 BC Middle Bronze Age Length: 77.46 millimetres Diameter: 28.03 millimetres (spiral) Thickness: 1.16 millimetres Weight: 28 grammes Pair with 1974,1201.342 [which is recorded Add.9455vol3_p747 /2] Egger sale Sotheby's 25 June 1891 Lot 113

BM 1974,1201.345 & 346 2 Gold 'spectacle' pendants:

345 plain wire tightly spiralled at ends, but twisted in central loop segment. Romania,Timiş (county),Timişoara,Temesvár) River Danube 1600-1200 BC Middle Bronze Age Length: 37.26 millimetres Width: 46.32 millimetres

Thickness: 1.38 millimetres Diameter: 21 millimetres (spiral) Diameter: 20.08 millimetres Weight: 14.2 grammes. Egger sale Sotheby's 25 June 1891 Lot 114 Exhibited 1998 9 Feb-3 May, India, Mumbai, Sir Caswasjee Jahangir Hall, The Enduring Image 1997 13 Oct-1998 5 Jan, India, New Delhi, National Museum, The Enduring Image.

346 old 'spectacle' pendant: plain wire tightly spiralled at ends, but twisted in central loop segment. Romania,Timiş (county),Timişoara,Temesvár) River Danube 1600-1200 BC Middle Bronze Age Length: 36.04 millimetres Width: 45.97 millimetres

Thickness: 1.38 millimetres Diameter: 21 millimetres (spiral) Diameter: 20.08 millimetres (spiral) Weight: 14.2 grammes Egger sale Sotheby's 25 June 1891 Lot 114 [Same exhibition details as above][Note that the object looks very similar to 345]

AP, August 2010, last item added March 2012

Further References

Website for the Barbier-Mueller Museums

Sotheby's sale catalogues (details given in each entry)

Waterfield, Hermoine and J.C.H. King. 2006. 'Provenance: Twelve collectors of ethnographic art in England 1760-1990' Somogy Art publishers, Barbier-Mueller Museum, Geneva